Political compromises – like the debt-limit deal – have never been substitutes for lasting solutions

Published in Political News

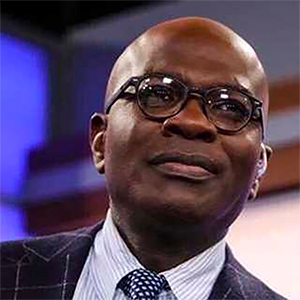

The compromise to avoid default on the U.S. debt passed muster, eventually. President Joe Biden and Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy pulled it off.

The nation can breathe, at least for the next two years. And yet, the far right is unhappy, many Democrats from the progressive wing are similarly annoyed, and the gnawing problem – the ballooning national debt – that is at the bottom of this compromise hasn’t gone away.

But isn’t this precisely what politics is all about? As Biden said in a formal statement on the deal, “The agreement represents a compromise, which means not everyone gets what they want.” And he concluded: “That’s the responsibility of governing.”

Political scientists have long pondered over this exact topic: compromises. There seems to be a quasi-consensus that good governing demands them — the more, the better.

As a historian, I’m here to make the case that compromises are rarely a lasting solution. It’s true that they buy time. Also, they may be necessary to face an emergency. But they are usually ugly, like battles or slaughterhouses. Compromises leave many spattered with blood and gore.

There’s nothing wrong with the spirit of compromise, generally speaking. As Thomas Jefferson said, experience teaches “the reasonableness of mutual sacrifices of opinion among those who are to act together.”

“When we cannot do all we would wish,” Jefferson determined, we should be content in “doing what good we can.”

The flip side is that compromises, or, in Jefferson’s words, the portion of good that can be done, often add up to hastily concocted responses to crises. And politics is – or should be – an art more ambitious than the management of crises and emergencies. Politics is nurtured by vision. It sees into the future and goes beyond the quest for last-minute, temporary solutions.

The Three-Fifths Compromise comes immediately to mind as an example of the poor quality – and only temporary utility – of compromise. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, there was an urgency to fathom how to apportion representation. In the new nation, what would be the number of representatives each state would get?

It was clear to all delegates that the tally had to be based somehow on each state’s population. More populous states would receive more representatives. But how to count enslaved persons? In the minds of these 18th-century men, the question was: Were they “inhabitants” or “property,” like cattle?

The debate soon turned rough. The clock was ticking. Were it not for two leaders, James Wilson from Pennsylvania and Charles Pinckney from South Carolina, the convention would have probably nose-dived into chaos.

The Three-Fifths Compromise, written into the Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the new Constitution, was how these two leaders managed the crisis. Non-free persons who display, in the wording of Federalist #54, a “mixed character of persons and of property,” will be counted not as whole persons but as three-fifths of a free person.

The compromise enabled the Constitution to be drafted, and later ratified, by nine of the 13 states comprising the union. It’s the proof that compromises, no matter how horrible, are used to solve seemingly intractable problems – but at a cost.

In 1819, after the Missouri territory applied for statehood, another big crisis shook the nation’s marrow. Would the new state make slavery legal?

At that moment, it was clear that breaking the balance of power between the 11 Northern states that opposed the expansion of slavery and the 11 Southern states that didn’t want to restrict human bondage would put the nation in serious jeopardy.

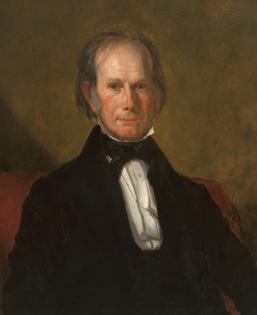

But the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay from Kentucky – aka the “Great Compromiser” – was able to broker the Missouri Compromise. The idea, this time, was that Missouri would become a state without any restriction over slavery; and Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, would enter the union as a state where slavery was outlawed.

On March 6, 1820, President James Monroe signed the compromise into law. Just like Clay, he would emerge from this adventure as the savior of the nation, so much so that he went on to be elected to a second term by an almost unanimous vote.

Slaveholders were appeased, and the union saved. But the Missouri Compromise, like the Three-Fifths Compromise, did nothing to fix the problems that had caused the crises in the first place. Human bondage in the young country persisted.

The history of the United States is fraught with political compromises. Many of them were ugly, at once a success and a failure.

Compromises are often flimsy and abet major problems in the long run. Moreover, by calling the public attention to the few protagonists who play the game, they also distract. The compromise gives a platform to the “heroes” and “saviors” – in the most recent case, Biden and McCarthy.

It can be dangerous to assume that politics, by its nature, only requires fast-moving, situation-assessing, occasion-grasping leaders who are eager to compromise – especially prominent and famous ones.

In politics, lasting solutions that would likely protect the common good come not from shrewd compromisers after a couple of weeks of pushing and pulling. They are ushered in by bipartisan measures that require much more time and patience.

Beyond and above the frantic interplay among those in charge, there are the myriad standing committees, subcommittees, commissions and all the organisms of which Congress is made.

Real solutions that would reflect the democratic nature of U.S. government entail the daily work that takes place through deliberative discussions in Congress that allow the weighing of pros and cons.

The not-very-famous representatives who, day in and day out, participate in committees and commissions have time, focus and patience. Sometimes – quite often, indeed – they churn out notable bipartisan agreements.

It may not be sensational, but such regular organisms, not heroes and saviors, represent the real embodiment of democracy, of “We, the people.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

House approval of debt ceiling deal a triumph of the political center

80 is different in 2023 than in 1776 – but even back then, a grizzled Franklin led alongside a young Hamilton

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments