The Supreme Court may soon diminish Black political power, undoing generations of gains

Published in Political News

Back in 2013, the Supreme Court tossed out a key provision of the Voting Rights Act regarding federal oversight of elections. It appears poised to abolish another pillar of the law.

In a case known as Louisiana v. Callais, the court appears ready to rule against Louisiana and its Black voters. In doing so, the court may well abolish Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, a provision that prohibits any discriminatory voting practice or election rule that results in less opportunity for political clout for minority groups.

The dismantling of Section 2 would open the floodgates for widespread vote dilution by allowing primarily Southern state legislatures to redraw political districts, weakening the voting power of racial minorities.

The case was brought by a group of Louisiana citizens who declared that the federal mandate under Section 2 to draw a second majority-Black district violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment and thus served as an unconstitutional act of racial gerrymandering.

There would be considerable historical irony if the court decides to use the 14th Amendment to provide the legal cover for reversing a generation of Black political progress in the South. Initially designed to enshrine federal civil rights protections for freed people facing a battery of discriminatory “Black Codes” in the postbellum South, the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause has been the foundation of the nation’s modern rights-based legal order, ensuring that all U.S. citizens are treated fairly and preventing the government from engaging in explicit discrimination.

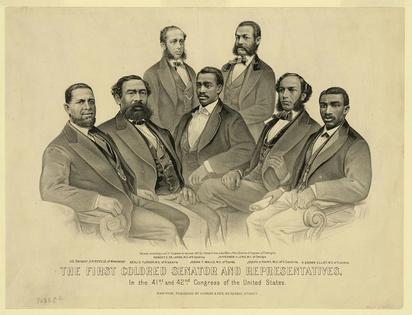

The cornerstone of the nation’s “second founding,” the Reconstruction-era amendments to the Constitution, including the 14th Amendment, created the first cohort of Black elected officials.

I am a historian who studies race and memory during the Civil War era. As I highlight in my new book “Requiem for Reconstruction,” the struggle over the nation’s second founding not only highlights how generational political progress can be reversed but also provides a lens into the specific historical origins of racial gerrymandering in the United States.

Without understanding this history – and the forces that unraveled Reconstruction’s initial promise of greater racial justice – we cannot fully comprehend the roots of those forces that are reshaping our contemporary political landscape in a way that I believe subverts the true intentions of the Constitution.

Political gerrymandering, or shaping political boundaries to benefit a particular party, has been considered constitutional since the nation’s 18th-century founding, but racial gerrymandering is a practice with roots in the post-Civil War era.

Expanding beyond the practice of redrawing district lines after each decennial census, late 19th-century Democratic state legislatures built on the earlier cartographic practice to create a litany of so-called Black districts across the postbellum South.

The nation’s first wave of racial gerrymandering emerged as a response to the political gains Southern Black voters made during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant in the 1870s. Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina and Louisiana all elected Black congressmen during that decade. During the 42nd Congress, which met from 1871 to 1873, South Carolina sent Black men to the House from three of its four districts.

Initially, the white Democrats who ruled the South responded to the rise of Black political power by crafting racist narratives that insinuated that the emergence of Black voters and Black officeholders was a corruption of the proper political order. These attacks often provided a larger cultural pretext for the campaigns of extralegal political violence that terrorized Black voters in the South, assassinated political leaders, and marred the integrity of several of the region’s major elections.

Following these pogroms during the 1870s, southern legislatures began seeking legal remedies to make permanent the counterrevolution of “Redemption,” which sought to undo Reconstruction’s advancement of political equality. A generation before the Jim Crow legal order of segregation and discrimination was established, southern political leaders began to disfranchise Black voters through racial gerrymandering.

These newly created Black districts gained notoriety for their cartographic absurdity. In Mississippi, a shoestring-shaped district was created to snake and swerve alongside the state’s famous river. North Carolina created the “Black Second” to concentrate its African American voters to a single district. Alabama’s “Black Fourth” did similar work, leaving African American voters only one possible district in which they could affect the outcome in the state’s central Black Belt.

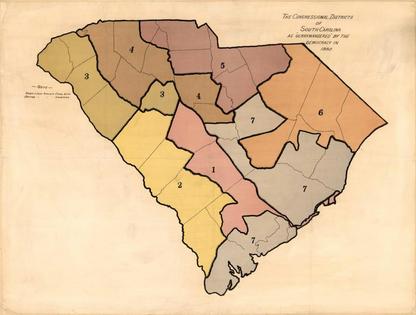

South Carolina’s “Black Seventh” was perhaps the most notorious of these acts of Reconstruction-era gerrymandering. The district “sliced through county lines and ducked around Charleston back alleys” – anticipating the current trend of sophisticated, computer-targeted political redistricting.

Possessing 30,000 more voters than the next largest congressional district in the state, South Carolina’s Seventh District radically transformed the state’s political landscape by making it impossible for its Black-majority to exercise any influence on national politics, except for the single racially gerrymandered district.

Although federal courts during the late 19th century remained painfully silent on the constitutionality of these antidemocratic measures, contemporary observers saw these redistricting efforts as more than a simple act of seeking partisan advantage.

“It was the high-water mark of political ingenuity coupled with rascality, and the merits of its appellation,” observed one Black congressman who represented South Carolina’s 7th District.

The political gains of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, sometimes called the “Second Reconstruction,” were made tangible by the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The law revived the postbellum 15th Amendment, which prevented states from creating voting restrictions based on race. That amendment had been made a dead letter by Jim Crow state legislatures and an acquiescent Supreme Court.

In contrast to the post-Civil War struggle, the Second Reconstruction had the firm support of the federal courts. The Supreme Court affirmed the principal of “one person, one vote” in its 1962 Baker v. Carr and 1964 Reynolds v. Sims decisions – upending the Solid South’s landscape of political districts that had long been marked by sparsely populated Democratic districts controlled by rural elites.

The Voting Rights Act gave the federal government oversight over any changes in voting policy that might affect historically marginalized groups. Since passage of the 1965 law and its subsequent revisions, racial gerrymandering has largely served the purpose of creating districts that preserve and amplify the political representation of historically marginalized groups.

This generational work may soon be undone by the current Supreme Court. The court, which heard oral arguments in the Louisiana case in October 2025, will release its decision by the end of June 2026.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Robert D. Bland, University of Tennessee

Read more:

Supreme Court redistricting ruling could upend decades of voting rights law – and tilt the balance of power in Washington

Voting rights at risk after Supreme Court makes it harder to challenge racial gerrymandering

What everyone should know about Reconstruction 150 years after the 15th Amendment’s ratification

Robert D. Bland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments