Trump’s offshore wind energy freeze: What states lose if the executive order remains in place

Published in Political News

A single wind turbine spinning off the U.S. Northeast coast today can power thousands of homes – without the pollution that comes from fossil fuel power plants. A dozen of those turbines together can produce enough electricity for an entire community.

The opportunity to tap into such a powerful source of locally produced clean energy – and the jobs and economic growth that come with it – is why states from Maine to Virginia have invested in building a U.S. offshore wind industry.

But much of that progress may now be at a standstill.

One of Donald Trump’s first acts as president in January 2025 was to order a freeze on both leasing federal areas for new offshore wind projects and issuing federal permits for projects that are in progress.

The order and Trump’s long-held antipathy toward wind power are creating massive uncertainty for a renewable energy industry at its nascent stage of development in the U.S., and ceding leadership and offshore wind technology to Europe and China.

As a professor of energy policy and former undersecretary of energy for Massachusetts, I’ve seen the potential for offshore wind power, and what the Northeast, New York and New Jersey, as well as the U.S. wind industry, stand to lose if that growth is shut down for the next four years.

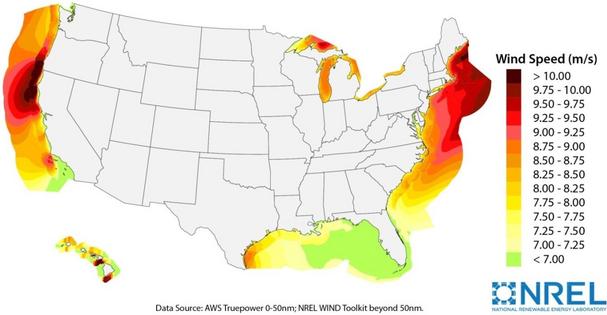

The Northeast’s coastal states are at the end of the fossil fuel energy pipeline. But they have an abundant local resource that, when built to scale, could provide significant clean energy, jobs and supply chain manufacturing. It could also help the states achieve their ambitious goals to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and their impact on climate change.

The Biden administration set a national offshore wind goal of 30 gigawatts of capacity in 2030 and 110 gigawatts by 2050. It envisioned an industry supporting 77,000 jobs and powering 10 million homes while cutting emissions. As recently as 2021, at least 28 gigawatts of offshore wind power projects were in the development or planning pipeline.

With the Trump order, I believe the U.S. will have, optimistically, less than 5 gigawatts in operation by 2030.

That level of offshore wind is certainly not enough to create a viable manufacturing supply chain, provide lasting jobs or deliver the clean energy that the grid requires. In comparison, Europe’s offshore wind capacity in 2023 was 34 gigawatts, up from 5 gigawatts in 2012, and China’s is now at 34 gigawatts.

Offshore wind is already a proven and operating renewable power source, not an untested technology. Denmark has been receiving power from offshore wind farms since the 1990s.

The lost opportunity to the coastal U.S. states is significant in multiple areas.

Trump’s order adds deep uncertainty in a developing market. Delays are likely to raise project costs for both future and existing projects, which face an environment of volatile interest rates and tariffs that can raise turbine component costs. It is energy consumers who ultimately pay through their utility bills when resource costs rise.

The potential losses to states can run deeper. The energy company Ørsted had estimated in early 2024 that its proposed Starboard Offshore Wind project would bring Connecticut nearly US$420 million in direct investment and spending, along with employment equivalent to 800 full-time positions and improved energy system reliability.

Massachusetts created an Offshore Wind Energy Investment Trust Fund to support redevelopment projects, including corporate tax credits up to $35 million. A company planning to build a high-voltage cable manufacturing facility there pulled out in January 2025 over the shift in support for offshore wind power. On top of that, power grid upgrades to bring offshore wind energy inland – critical to reliability for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from electricity – will be deferred.

Technology innovation in offshore wind will also likely move abroad, as Maine experienced in 2013 after the state’s Republican governor tried to void a contract with Statoil. The Norwegian company, now known as Equinor, shifted its plans for the world’s first commercial-scale floating wind farm from Maine to Scotland and Scandinavia.

Development of energy projects, whether fossil or renewable, is extremely complex, involving multiple actors in the public and private spheres. Uncertainty anywhere along the regulatory chain raises costs.

In the U.S., jurisdiction over energy projects often involves both state and federal decision-makers that interact in a complex dance of permitting, studies, legal regulations, community engagement and finance. At each stage in this process, a critical set of decisions determines whether projects will move forward.

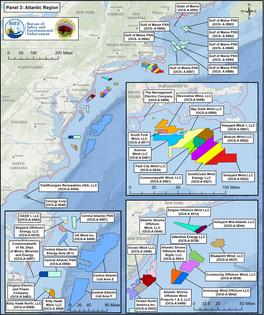

The federal government, through the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Offshore Energy Management, plays an initial role in identifying, auctioning and permitting the offshore wind areas located in federal waters. States then issue requests for proposals from companies wishing to sell wind power to the grid. Developers who win bureau auctions are eligible to respond. But these agreements are only the beginning. Developers need approval for site, design and construction plans, and several state and federal environmental and regulatory permits are required before the project can begin construction.

Trump targeted these critical points in the chain with his indefinite but “temporary” withdrawal of any offshore wind tracts for new leases and a review of any permits still required from federal agencies.

A thriving offshore wind industry has the potential to bring jobs, as well as energy and economic growth. In addition to short-term construction, estimates for supply chain jobs range from 12,300 to 49,000 workers annually for subassemblies, parts and materials. The industry needs cables and steel, as well as the turbine parts and blades. It requires jobs in shipping and the movement of cargo.

To deliver offshore wind power to the onshore grid will also require grid upgrades, which in turn would improve reliability and promote the growth of other technologies, including batteries.

Taken all together, an offshore wind energy transition would build over time. Costs would come down as domestic manufacturing took hold, and clean power would grow.

While environmental goals drove initial investments in clean energy, the positive benefits of jobs, technology and infrastructure all became important drivers of offshore wind for the states. Tax incentives, including from the Inflation Reduction Act, now in doubt, have supported the initial financing for projects and helped to lower costs.

It’s a long-term investment, but once clear of the regulatory processes, with infrastructure built out and manufacturing in place, the U.S. offshore wind industry would be able to grow more price competitive over time, and states would be able to meet their long-term goals.

The Trump order creates uncertainty, delays and likely higher costs in the future.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Barbara Kates-Garnick, Tufts University

Read more:

How the oil industry and growing political divides turned climate change into a partisan issue

Why US offshore wind power is struggling – the good, the bad and the opportunity

Surviving fishing gear entanglement isn’t enough for endangered right whales – females still don’t breed afterward

Barbara Kates-Garnick receives funding as an Outside Director for Anbaric Transmission, which has no operating projects related to offshore wind. She has received funding for a research project through Tufts University jointly funded by NOWRDC and the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center. She serves on the board of several nonprofits that are not politically active organizations.

Comments