Politics

/ArcaMax

Commentary: Has the West given up protecting its citizens?

Two centuries ago, gentlemen routinely carried swords or pistols to protect themselves, their families and their property. On the unlit dirt backroads of England or colonial America, armed highwaymen like Dick Turpin could demand “your money or your life!” without warning.

There was no 911. No local law enforcement or highway patrol on the ...Read more

Lisa Jarvis: America's year of health-care chaos will have these consequences

The unprecedented turmoil at the top U.S. health agencies, under the leadership of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is sure to have a long-term impact on the well-being of Americans. Although Kennedy’s mantra has been to “Make America Healthy Again,” the most visible changes he and his allies have made within the ...Read more

Michael Hiltzik: Blondie and Dagwood are entering the public domain, but Betty Boop still may be trapped in copyright jail

Here's a quick quiz about some cultural icons on the verge of experiencing a kind of rebirth:

1. What was the original storyline of the Dagwood and Blondie comics?

2. What was Blondie's maiden name?

3. In her original incarnation, what animal was Betty Boop?

Those characters all date from 1930, which means that on New Year's Day 2026 they ...Read more

Commentary: The Supreme Court finally pushed back against Trump

In one of its most consequential rulings of the year, just before breaking for the holidays last week the Supreme Court held that President Donald Trump acted improperly in federalizing the National Guard in Illinois and in activating troops across the state. Although the case centered on the administration’s deployments in Chicago, the court�...Read more

Commentary: The foreign policy moves Donald Trump got right in 2025

For President Donald Trump’s supporters, 2025 has been a year of transformation. For his opponents, it’s been nothing short of a long nightmare. The holiday season is a perfect time to look back, reflect and remember the consequential moments of the past year.

As human beings, we generally fixate on the negative. Indeed, there are a ton of ...Read more

Editorial: Illinois must move fast to ensure consumers don't run short on power

Fifteen months ago, this page warned that Illinois faced likely electricity shortages in the next few years if Gov. JB Pritzker’s landmark Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, passed in 2021, wasn’t made more flexible to allow existing natural gas-fired power plants to run past the law’s closure deadlines.

Since then, Illinoisans have watched ...Read more

Commentary: SNAP isn't a negotiating tool. It's a lifeline

Millions of families just survived the longest shutdown in U.S. history. Now they’re bracing again as politicians turn food assistance into a bargaining chip.

Food assistance should not be subject to politics, yet the Trump administration is now requiring over 20 Democratic-led states to share sensitive SNAP recipient data—including Social ...Read more

Editorial: A badly misguided honor for Charlie Kirk

In a society that treasures and protects free speech, it’s important to focus a spotlight on people who were hunted down because their ideas were too dangerous or offended too many people.

These names are threaded through the history of this nation, and of Florida as well. Teaching schoolchildren and reminding everyone of their importance is ...Read more

David Fickling: The positive climate news you may have missed this year

So much climate news comes out in any given week that it can be hard to keep up with it all. Much is gloomy, but there are positive developments all the time — so many, in fact, that it’s easy to miss some of the things that have been happening.

For the past few years, I’ve been compiling year-end lists of the more neglected good and bad...Read more

Commentary: What 2025 meant for animals

It was a year when the ground finally started to shift under our feet. So much felt uncertain in 2025—politics, weather, the pace of the world itself—but one thing became beautifully, unmistakably clear: Compassion is reshaping the way scientists conduct experiments and how we eat, dress and live in other ways. For animals, it was a year of ...Read more

Gustavo Arellano: Trump regime's lies against immigrants in 2025 even did Frank Sinatra dirty

This is a column about lies. Big lies. Presidential lies. Dumb lies. The type of lies that have made life in the United States a daily dumpster fire of bad news. The kind of lies that would've made Frank Sinatra want to knock out a palooka.

More on Ol' Blue Eyes in a bit.

For now let me tell you about one victim of President Donald Trump's ...Read more

Abby McCloskey: What's worse than cherry-picked government data? None at all

It was hard to know what to believe this year. In the old days, there were conspiracies about the moon landing. These days, it feels like there’s a conspiracy about everything — that the truth is up for grabs, alongside crusty government datasets.

Some people chose to verify what they heard with multiple sources, including legacy media. ...Read more

Commentary: The Venezuelan 'threat' is all Trumped up

I know boats. Catamarans where water laps at your legs. Fishing boats with bright colors and splintered seats. Even though I grew up in the heart of Silicon Valley in San José, California, I come from a line of Venezuelans who were fed by the ocean. And, like all the fishermen before him, my father’s sunworn skin smelled of salt.

My father ...Read more

Commentary: America tried something new in 2025. It's not going well

Is there a dumpster somewhere to torch and bury this year of bedlam, 2025?

We near its end with equal amounts relief and trepidation. Surely we can’t be expected to endure another such tumultuous turn around the sun?

It was only January that Donald Trump moved back into the White House, apparently toting trunkloads of gilt for the walls. ...Read more

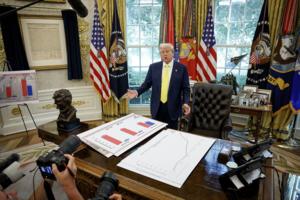

Editorial: Trump makes headway on smaller federal workforce

For the first time in decades, the federal bureaucracy is getting smaller.

According to the latest federal jobs report, the government has shed roughly 271,000 civilian positions in the past year, putting President Donald Trump within striking distance of his stated goal to cut 300,000 federal jobs by year’s end. In an era when government ...Read more

Commentary: Faith leaders -- 2025 was a year of setbacks and celebration

The end of a calendar year is always a good time to reflect on the time that has passed. We’d like to share our reflections on the 12 months of messages we have been privileged to share with you through the pulpit of the opinion pages.

We begin with the obvious: 2025 was a year of major setbacks.

Following the inauguration of a new ...Read more

Editorial: Trump tramples on a cherished monument

Susie Wiles was right about one thing.

In a revealing Vanity Fair article, President Donald Trump’s chief of staff said he thinks “there’s nothing he can’t do. Nothing. Zero. Nothing.”

Trump confirmed it by having his handpicked board rename one of the nation’s most cherished memorials “The Donald J. Trump and the John F. Kennedy...Read more

Ronald Brownstein: 2025 turned Trump's biggest strength against him

As usual when Donald Trump occupies the White House, 2025 condensed a decade’s worth of political upheaval into a single year. Identifying the most important of those developments is like picking through the wreckage to find a few family heirlooms after a tornado has torn through the neighborhood.

But in the swarm of conflicts, controversies,...Read more

Commentary: Prison methods are as bad as you've heard, and spilling onto the streets

I was one of the researchers in the well-known Stanford prison experiment in 1971, demonstrating the destructive dynamics that are generated when one group of people — randomly assigned as “guards” — is given near total power over a group of “prisoners.” In six short days, inside a simulated prison environment, authoritarian forms of...Read more

Andreas Kluth: Dismiss the Doomsday Clock at your own peril

We’re once again approaching the annual resetting of the Doomsday Clock. Last January, the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, a group of very smart people, moved the hands of their metaphorical clock to 89 seconds to midnight, where midnight represents doomsday, apocalypse, Armageddon, extinction, or whatever you ...Read more