Map wars in the Middle East: How cartographers charted and helped shape a regional conflict

Published in Political News

Maps are ubiquitous – on phones, in-flight and car displays, and in textbooks the world over. While some maps delineate and name territories and boundaries, others show different voting blocs in elections, and GPS devices help drivers navigate to their destination.

But no matter the purpose, all maps have something in common: They are political. Making maps is about making decisions about what to omit and what to include. They are subject to selection, classification, abstractions and simplifications. And studying the choices that go into maps, as I do, can reveal different stories about land and the people who claim it as theirs.

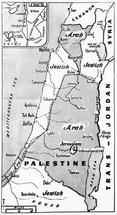

Nowhere is this more true than in the contested regions that today include modern-day Israel and the Palestinian territories. Since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, different governmental and nongovernmental organizations and political interest groups have engaged in what can best be described as “map wars.”

Maps of the region use the naming of places, the position of borders and the inclusion or omission of certain territories to present contrasting geopolitical visions. To this day, Israel or the Palestinian territories may fall off some maps, depending on the politics of their makers.

This is not exclusive to the Middle East – “map wars” are underway across the globe. Some of the more well-known examples include disputes between Ukraine and Russia, Taiwan and China, and India and China. All are engaged in controversies over the territorial integrity of nation-states.

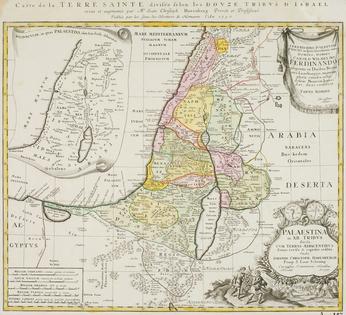

Traditionally, maps have been used to represent cosmologies, cultures and belief systems. By the 17th century, maps that represented spatial relations within a given territory beaome important to the making of nation-states. Such official maps helped annex territories and determine property rights. Indeed, to map a territory meant to know and control it.

More recently, the tools for making maps have become more broadly accessible. Anyone with a computer and internet access can now make and share “alternative maps” that present different visions of a territory and make varied geopolitical claims.

And maps produced in a conflict region, such as Israel and the Palestinian territories, tell a rich story about the relationship between mapmaking and politics.

During the British Mandate of Palestine from 1917 to 1947, British surveyors mapped the territories to exercise their control over the land and its people. It was an attempt to supersede the more informal Ottoman land claims of the time.

By the founding of Israel in 1948, only about 20% of the total area of what is known as historic Palestine had been mapped – a fact that has fueled land disputes to this day. The British mapping efforts and their omissions enabled the newly established state of Israel to declare most of the territories as state land, thereby delegitimizing Palestinian land claims.

Maps also helped build the Israeli state. Surveyors and planners mapped the land to allocate land rights, and they helped build the state’s infrastructure, including roads and railroads.

But maps also helped create a sense of nationhood. Maps representing a nation’s shape by delineating its national borders are known as “logo” maps. They can enhance feelings of national unity and a sense of national belonging.

Once established, the Israeli state remade the maps of the region. An Israeli Governmental Names Commission came up with Hebrew names to replace formerly Arab and Christian names for different towns and villages on the official map of Israel. At the same time, formerly Palestinian topographies and places were omitted from the map.

Some Palestinian mapmakers, however, continue to make maps that include Palestinian named sites and depict pre-1948 historic Palestine – an area that stretches from River Jordan in the east to the Mediterranean Sea in the west. Such maps are used to advocate for Palestinians’ right to land and foster a sense of national belonging.

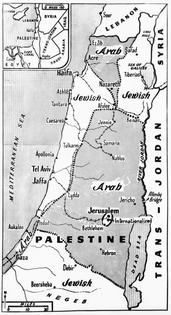

At the same time, Palestinian cartographers who work with the Palestinian Authority – the government body that administers partial civil control over Palestinian enclaves in the West Bank – make official maps of the West Bank and Gaza in the hope of establishing a future state of Palestine. They align their maps with United Nations efforts to map the territories according to international law by demarking the West Bank and Gaza as separate from and as occupied by Israel.

After the 1967 war between Israel and its Arab neighbors, Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. As a result, map wars intensified, especially between different fractions within Israel. The left-wing “peace camp,” which was dedicated to territorial compromises with the Palestinians, was pitted against an Israeli right wing committed to reclaiming the “Promised Land” for ensuring Israeli security.

Such incompatible geopolitical visions continue to be reflected in the maps produced. “Peace camp” maps adhere to the delineation of the territories according to international law. For example, they include the Green Line – the internationally recognized armistice line between the West Bank and Israel. Official maps produced by the Israeli government, by contrast, stopped delineating the Green Line after 1967.

Not only have different interest groups and political actors used maps of the region to put forth competing geopolitical claims, but maps have also played a central role in sporadic efforts to establish peace in the region.

The 1993 Oslo Accords, for example, relied on maps to provide the framework for Palestinian self-rule in return for security for Israel. The aim was that after a five-year interim period, a permanent peace settlement would be negotiated based on the borders laid out in these maps.

Consequently, Palestinian planners and surveyors mapped the territory allocated to a future state of Palestine. With the Oslo Accords promising only a future state – but with its borders and level of sovereignty still uncertain – Palestinian experts nevertheless continue to prepare for governing the territories by mapping them.

The Oslo maps are used to this day to delineate geopolitical visions of Israel and a future state of Palestine that are based on international law. But for many Israelis, the Oslo vision of a two-state solution has died – the attack by Hamas, the Palestinian nationalist political organization that governs Gaza, on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, was its last blow.

The subsequent war between Israel and Hamas, currently subject to a cease-fire, has from the outset involved maps.

In December 2023, the Israeli military posted an online “evacuation map” that divided the Gaza Strip into 623 zones. Palestinians could go online – provided they have access to electricity and internet in a territory plagued by blackouts – to find out whether their neighborhood was called upon to evacuate. Israeli military commanders used this map to decide where to launch airstrikes and conduct ground maneuvers.

But the map served a political aim, too: to convince a skeptical world that Israel was taking care to protect civilians. Regardless, its introduction caused confusion and fear among Palestinians.

Maps aren’t just for making sense of the past and present – they help people imagine the future, too. And different maps can reveal conflicting geopolitical visions.

In January 2024, for example, various Israeli right-wing and settler organizations organized the Conference for the Victory of Israel. The aim was to plan for resettling Gaza and increase Jewish settlements in the West Bank. Speakers advocated for transferring Palestinians from the Strip to the Sinai through “voluntary emigration.” With Jewish settlers planning for the return to Gaza, and speakers citing both the Bible and Israeli security for justifications, an oversized map showed the location of proposed Jewish settlements.

Similarly, the Israeli Movement for Settlement in Southern Lebanon has published maps of planned Jewish settlements in Southern Lebanon.

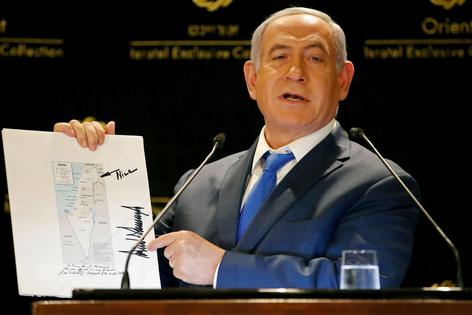

Such maps reveal the desire by some in Israel for a “Greater Israel” – an area described in 1904 by Theodor Herzl, considered the father of modern-day Zionism, as spanning from the brook of Egypt to the Euphrates.

Unsurprisingly, Palestinians make different maps for envisioning the future. Palestine Emerging – a Palestinian and international initiative that brings together various experts, organizations, and funders – uses maps that connect Gaza to the West Bank and the wider region.

Their aim is to transform Gaza into a commercial hub for trade, tourism and innovation and to integrate it into the global economy. Accordingly, maps of urban projects, airports and seaports overlay the cartographic contours of Gaza; and a Gaza-West Bank corridor, which would be sealed for Israeli security, could connect the two geographically separate Palestinian territories.

Such maps reflect the efforts by Palestinian stakeholders to continue surveying the territories that, since the Oslo Accords, were to make up the future state of Palestine.

With the current U.S. administration more aligned with right-wing Israeli policies, maps of Greater Israel may guide what Hagit Ofran from Peace Now calls the beginning of a new “Greater Israel” policy period.

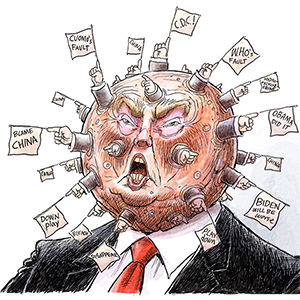

In a novel twist, U.S. President Donald Trump on Feb. 4, 2025, floated a plan for the U.S. to “take over” Gaza, moving its current inhabitants out and turning the enclave into “"the Riviera of the Middle East.”

Such a move would amount to another attempt to remake borders across the Middle East. It would not, however, end the “map wars” in Israel/Palestine.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Christine Leuenberger, Cornell University

Read more:

Why paper maps still matter in the digital age

How – and why – Google is transforming the map

Maps show – and hide – key information about Ukraine war

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation through the Science and Technology Studies (STS) Program, award #1152322. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or any other entity.

Comments