Supreme Court’s ruling in Trump v. United States would have given Nixon immunity for Watergate crimes — but 50 years ago he needed a presidential pardon to avoid prison

Published in Political News

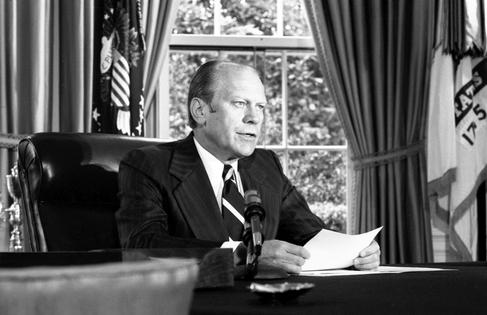

Gerald Ford knew Richard Nixon could be prosecuted for crimes he committed as president. That was simply a fact, when President Ford gave his predecessor “a full, free, and absolute pardon” 50 years ago this week.

Former presidents did not enjoy broad immunity from criminal prosecution until July 1, 2024, when six members of the Supreme Court created that privilege in Trump v. United States.

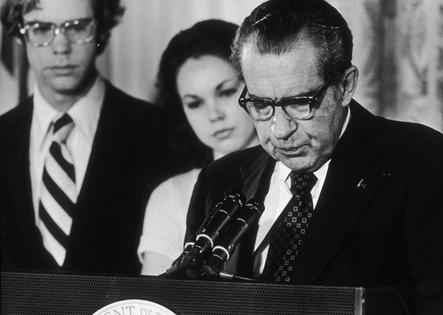

In 1974, when Nixon’s resignation seemed likely to lead to prosecution for his role in many of the crimes of Watergate, Republicans in the White House and Congress took their cue from the Constitution. Article II, Section 4 established that former presidents had criminal liability, not criminal immunity. Even after impeachment, conviction and removal, “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.”

Ford faced that fact squarely in his pardon proclamation: “As a result of certain acts or omissions occurring before his resignation from the Office of President, Richard Nixon has become liable to possible indictment and trial for offenses against the United States.”

Nixon had a right to a fair trial, Ford said. The Constitution guarantees that to all. But Ford raised doubts about whether America would be able to give Nixon a fair trial until months, perhaps years, elapsed. That was his justification for pardoning Nixon.

It wasn’t good enough for most Americans.

Only 26% of Americans supported the pardon in one poll, with 59% opposed.

Reporters interviewed outraged citizens.

“What about the others in his administration who are being tried?” asked John Dawdy, a Vietnam veteran and law student. After all, Nixon’s co-conspirators, including a former attorney general and former White House chief of staff, received fair trials.

Joseph Hickel, a refugee from Czechoslovakia, saw “a danger of future crimes” by presidents if Nixon’s went unpunished. Ann Robinson of Cerritos, California, said, “Giving that pardon makes it seem that the man in office is a king.”

Opinion shifted as Watergate receded in memory, and by 1986, one poll found only 39% opposed to the Nixon pardon and 54% in favor.

Sen. Ted Kennedy, a Democrat from Massachusetts and a critic of the pardon in 1974, later concluded that Ford was right and gave him a Profile in Courage Award in 2001 for taking an unpopular but conscientious stand.

During the Donald Trump administration, when another president was under investigation for impeachable and indictable offenses, public opinion of the Nixon pardon shifted again, with Americans perfectly polarized: 38% in favor, 38% against.

In light of the Trump experience, some historians looked back and saw the Nixon pardon in a new light: as a damaging precedent establishing presidential impunity.

This year, Americans face a new consequence of the pardon. Because Ford’s decision deprived the country of a precedent for prosecuting a former president, the six Republican-appointed justices on the Supreme Court were able to fill the void with what I see as a radical revision of the Constitution.

The court majority’s ruling that presidents are immune from prosecution for their “official acts” would have absolved most of Nixon’s Watergate crimes. Nixon used the CIA to obstruct the FBI’s Watergate investigation; created an illegal, unconstitutional secret police unit; sicced the IRS on political adversaries; commuted former Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa’s sentence for jury tampering and pension fund fraud in return for union support; and shook down campaign contributors in return for government favors.

Under Trump v. United States, Nixon wouldn’t have had to worry about a pardon. He could have explained away all of these crimes as “official acts” he took using the powers of the presidency.

The Supreme Court’s conservative justices, who see themselves as “originalists” and pride themselves on sticking to the literal text of the Constitution and original intent of its framers, have ironically provided a perfect example of the dangers of allowing justices to rewrite the Constitution to suit their current preferences.

The Watergate break-in occurred in the same year that Joe Biden entered national politics as a Democratic U.S. Senate candidate from Delaware. The newly elected Sen. Biden criticized the pardon the day after Ford issued it, saying, “It puts one man above the law.”

Biden couldn’t have known that 50 years later, during his last year in national politics, the Supreme Court would grant presidents license to commit Nixonian crimes – or worse – with the powers of their office and without any fear of punishment.

As part of his legacy, Biden has proposed a constitutional amendment to undo the damage done by Trump v. United States. Its name reflects the principle Biden invoked 50 years ago. It’s called the No One Is Above the Law Amendment. It would strip presidents of immunity from prosecution for crimes committed as “official acts.” As a soon-to-be-former president, Biden could have much to lose from the adoption of his own amendment.

This year’s Republican nominee has often expressed eagerness to prosecute Biden despite a lack of evidence of criminality. Under Trump v. United States, Biden enjoys broad immunity. Under the No One Is Above the Law Amendment, he would lose that privilege.

The amendment is not only an example of Biden putting the country before himself, it’s a profile in courage.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ken Hughes, University of Virginia

Read more:

‘Above the law’ in some cases: Supreme Court gives Trump − and future presidents − a special exception that will delay his prosecution

Supreme Court rules that Trump had partial immunity as president, but not for unofficial acts − 4 essential reads

Can Congress hold Trump accountable? 4 essential reads on a historic power struggle

Ken Hughes is a researcher with the Presidential Recordings Program of the University of Virginia's Miller Center. The program's work is funded in part by grants from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Comments