Indigenous Peoples Day offers a reminder of Native American history − including the violence they endured at the hands of Colonists

Published in Political News

For the third year, the United States will officially observe Columbus Day alongside Indigenous Peoples Day on Oct. 9, 2023.

In 2021, the Biden administration declared the second Monday in October as Indigenous Peoples Day.

I am a scholar of Colonial-Indigenous relations and think that officially recognizing Indigenous Peoples Day – and, more broadly, Native Americans’ history and survival – is important.

Yet, Indigenous Peoples Day and Columbus Day should also serve as a reminder of the violent past endured by Indigenous communities in North America.

This past – complete with settlers’ brutal tactics of violence – is often ignored in the U.S.

My research on New England examines the important role that settlers’ wars against Native Americans played in their colonization of the region.

This warfare often targeted Native American women and children and was often encouraged through scalp bounties – meaning people or local governments offering money in exchange for a Native American’s scalp.

Scalping describes the forceful removal of the human scalp with hair attached. The violent act is usually performed with a knife, but it can also be done by other means. Someone can scalp victims who are already dead, but there are also examples of people being scalped while they are still alive.

Different groups have historically used scalping to terrorize people.

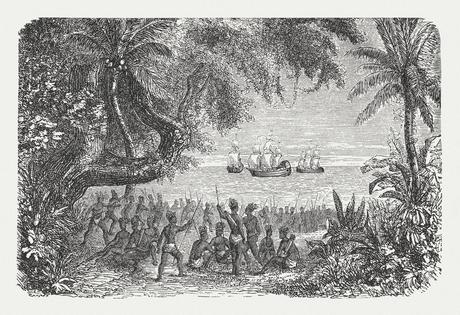

Native Americans certainly scalped white settlers dating back to the 1600s. Popular culture is full of examples of Native Americans scalping white settlers.

In several Indigenous cultures in North America, scalping was part of human trophy taking, which involves claiming human body parts as a war trophy. Scalps were taken during warfare as displays of military prowess or for ceremonial purposes. But just because scalping was practiced by some Native American societies, it does not mean that it was practiced by all.

Eyewitness accounts, histories and even art and popular films about the American West have perpetuated the false idea that scalping is a uniquely indigenous practice.

White settlers’ wide use of scalping against Indigenous peoples is far less acknowledged and understood. In fact, Colonists’ use of scalping against Native American people likely accelerated this practice.

Various European American colonizers also scalped Native American people from at least the 17th through the 19th centuries. It was a way to provide proof that someone killed a Native American person. Several North American colonial powers, from the British to the Spanish empires, paid bounties to people who turned in scalps of killed Native Americans.

Colonies, territories and states in what is now the U.S. used scalp bounties widely from the 17th through the 19th centuries.

Colonial governments in New England issued over 60 scalp bounties from the 1680s through the 1750s, typically during various conflicts between Colonists and Native Americans.

Massachusetts made the widest use of scalp bounties among the New England Colonies in the 1700s.

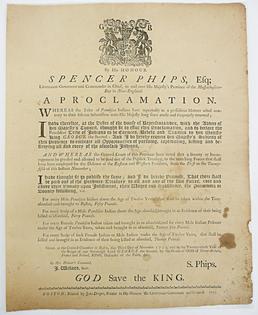

Massachusetts’ lieutenant governor issued one of the most notorious scalp bounty declarations in 1775. This declaration, called the Spencer Phips Proclamation of 1755, provides a glimpse into how this brutal system worked.

“For every scalp of such Female Indian or male Indian under the Age of Twelve Years, that shall be killed and brought in as Evidence of their being killed …, Twenty Pounds,” the declaration reads.

This reward was a large amount of money for Colonists, equivalent to more than 5,000 pounds, or US$12,000 in today’s currency. The scalp of a male Native American could fetch two and a half times this amount.

In the Colonial era, such violence was normalized by anti-Native American sentiment and a sense of racial superiority among Colonists.

And the violent trend was long-standing. As several historians point out, violence against and scalping of Native Americans also played a significant role in the conquest of California in 1846.

One historian has called California “the murder state” in the 1800s, as the scalping and massacres of Native Americans accompanied white settlers’ taking Native American land. State and federal officials, as well as several businesses, supported this genocide by paying bounties to scalp hunters.

From a contemporary perspective, the United Nations would consider the targeted killing of Indigenous women and children to be genocide.

Centuries later, California and Massachusetts have had different responses to their role in these sordid histories.

California has acknowledged “historic wrongdoings” and the violence committed against the Indigenous people who live in the state. In 2019, California Gov. Gavin Newsom set up a a Truth and Healing Council to discuss and examine the state’s historical relationship with Native Americans.

In Massachusetts, state officials have largely been silent on this issue. This places Massachusetts more in line with much of the United States.

This is true even as Massachusetts, under the leadership of then-Gov. Charlie Baker, put a special emphasis on genocide education in the school curriculum.

The legacies of violence and scalping are deeply rooted and can be observed in numerous parts of U.S. society today.

For instance, various communities, including Lovewell, Maine, and Spencer, Mass., are named after scalp bounty hunters. Locals are often not aware of the history behind these names. Such town names, and the history of violence connected to them, often hide in plain sight.

But if you look closely, from the writings of early Euro-American colonizers and American literature to popular sport mascots and state and town seals, the brutality wrought upon Indigenous people remains at the forefront of U.S. culture more than five centuries after it began.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more:

Indigenous Peoples Day: Why it’s replacing Columbus Day in many places

Why more places are abandoning Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples Day

Christoph Strobel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments