Women in Antarctica face assault and harassment – and a legacy of exclusion and mistreatment

Published in Political News

A federal report that, in the words of its key finding, “sexual assault, sexual harassment, and stalking are problems in the U.S. Antarctic Program community” – and that efforts “dedicated to prevention [are] nearly absent” – drew attention around the world. But as a historian of Antarctic science, I did not find it surprising at all.

The report, released in August 2022 by the National Science Foundation, which runs the United States Antarctic Program, found that many scientists and workers believe human resources staff “are dismissing, minimizing, shaming, and blaming victims who report sexual harassment and sexual assault.” A report with similar findings about its national program was released by the Australian Antarctic Division in late September 2022.

The fields of Antarctic science and exploration have long excluded women from the region altogether and still have a strong culture focused on masculinity and chauvinism.

The first Antarctic expedition to include women was the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition, in 1947-1948, a U.S.-based expedition with funding from the government and private sources, led by U.S. Navy Capt. Finn Ronne. His wife Edith “Jackie” Ronne accompanied her husband, as did Jennie Darlington, the wife of one of the pilots, Harry Darlington.

Their inclusion was groundbreaking. But their presence also was perceived by many in the polar community to contribute to tensions between the young and inexperienced men, “hardening into a mold of accusation, innuendo, and dissension. … Tension and turmoil were to take precedent over pioneering,” as one historian wrote.

Jackie Ronne would return to Antarctica several times. But at that first expedition’s conclusion, Jennie Darlington asserted that “women do not belong in the Antarctic” because of the harsh conditions, which might cause a person to require assistance or even rescue. She wrote, “Men should not be put in the position of endangering his own safety for another, lesser physical human.”

Darlington also reflected on the emotional burden she undertook. Many men, including her husband, believed that “Antarctica symbolized a haven, a place of high ideals and that inner peace men find only in an all-male atmosphere in primitive surroundings.” She wrote, “My job was to be as inconspicuous within the group as possible. I felt that all feminine instincts should be sublimated. … I was determined not to act like a woman in a man’s world.”

She also commented on the psychological difficulty for both the women: “It was a tenuous balance, in which as women, we bore the major responsibility for the men’s conduct toward us. … Any drawing of attention to myself, any gesture or indication that I expected certain courtesies, any show of bossiness or pretense would have been resented.”

The global scientific effort called the International Geophysical Year in 1957-1958 changed the nature of Antarctic research from relatively small, short-term expeditions to the establishment of permanent bases on the continent. But as various countries shaped their respective Antarctic programs, many were adamant that women would not be included.

U.S. Navy Adm. George Dufek, the supervisor of U.S. programs in Antarctica, declared in 1957 that “women will not be allowed in the Antarctic until we can provide one woman for every man,” implying that there would be no need for women in Antarctica except as sexual partners for the men.

Vivian Fuchs, the director of the British Antarctic Survey from 1958 to 1973, took a similar position in the 1950s and declared as late as 1982: “Should it happen one day that women are included as part of the base complement, problems will certainly arise [and] lead to the breakdown of that sense of unity which is so important to the group.”

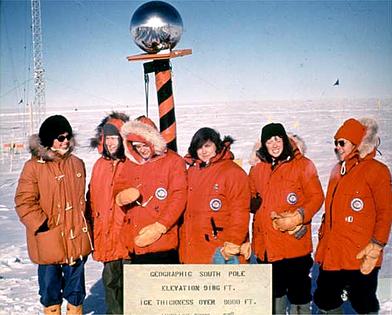

The first women to formally participate in United States fieldwork were those in the expedition led by geochemist Lois Jones in 1969. Jones was permitted by the National Science Foundation to visit Antarctica only if she could form an all-women’s expedition.

Her team of four was among the first six women to visit the South Pole, in a publicity stunt orchestrated by the U.S. Navy in which the women were labeled “powder puff explorers” by the media.

A senior New Zealand geologist, whom Jones had lobbied for assistance with her initial application, later appeared to regret it. He wrote a sexist screed declaring, “The flood gates opened and every feminist world-wide screamed sexism, racism etc. if they were refused an expensive three month Antarctic trip. It is an age-old desire of unmarried females to be where the boys are and in many I have met, there is no question this was the dominant urge.”

Irene Penden, the first woman to work in the Antarctic interior, went in 1970 to study the movement of very low radio frequency waves. But it wasn’t easy. She later wrote, “For whatever reason, probably because there had been so much foot-dragging about and resentment of the first women going there, a mythology had been created about the women who’d gone to the coast – that they had been a problem. I heard that their presence had been a problem and they had not been productive because they had not published anything yet.” Yet it had only been a few months since that first group of women had finished their research season, and generally it takes more than a year for field data to be converted into scientific articles.

Further, the U.S. Navy, which controlled the transportation to, from and within Antarctica, also argued that Penden should be forbidden because of the lack of women’s bathrooms on board ships and in the Antarctic generally. It is a complaint that was echoed throughout the period of women’s integration into Antarctic national programs through the 1990s, as well as in other settings such as the military and outer space.

While most principal investigators did not need to write a proposal to get a trip to Antarctica, to put pressure on the Navy, the National Science Foundation required that she write a specific proposal for a short-term trip, have it peer-reviewed, and get it approved internally. After “I went through that whole rigamarole … they kept dragging their feet,” she wrote. So Penden arranged to give a briefing on her work to relevant people from the National Science Foundation and the Navy so that Navy leadership “could see how totally scientific and professional I was [and] would realize that I was not some adventuress just trying to get down there where all the men were, which was the kind of thing they were saying.”

The admiral in question did not come to the meeting. However, he later gave permission for her travel if she could find a woman to accompany her. Rather than find another scientist, Penden was accompanied by a New Zealand mountaineer, Julia Vickers. While on the ice, Penden was warned by the station chief, “If you fail, there won’t be another woman on the Antarctic continent for a generation.”

One major result of the practice of excluding women and singling them out as outsiders was that behavior explicitly hostile to women became commonplace in Antarctica.

While women started being part of the United States research program in 1969, the British Antarctic Survey did not fully integrate until 1996, finally allowing women to spend the winter at their remote Halley Station. In the bases and expeditions mounted by both nations, and other countries too, Antarctica remained constructed as a place that was decidedly male.

Pornographic material was publicly consumed and even created. Walls were often decorated with images of nude or scantily clad women. The carpenter’s hut at Australia’s Mawson Station famously included the “Sistine Ceiling,” with clippings of over 90 Playboy models plastered over the ceiling and walls.

This remained at Mawson until 2005, 20 years after women were allowed to work at the station. That year it was destroyed by an unknown person to the disappointment of some, who felt the destroyer had “assumed the right to play heritage vandal or moral police for everyone.”

Today, the idea that Antarctica is a region dominated by adventurous hero-scientists persists. The stereotypical image of a man sporting an ice-encrusted beard remains the most emblematic visage of an Antarctic explorer. And this view of Antarctica as a place for men continues to create barriers to women’s participation both on stations and in remote fieldwork.

Indeed, Antarctic science remains highly male-dominated, which, during the early days of the #MeToo movement in 2017, revealed many troubling allegations about the dangers that women continued to face, including sexual harassment and even sexual assault. So while this recent National Science Foundation report may have many shocking and revealing elements, none of it is a surprise to any woman who has either worked or attempted to work in Antarctica.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Daniella McCahey, Texas Tech University. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

200 years ago, people discovered Antarctica – and promptly began profiting by slaughtering some of its animals to near extinction

200 years of exploring Antarctica – the world’s coldest, most forbidding and most peaceful continent

Daniella McCahey has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Comments