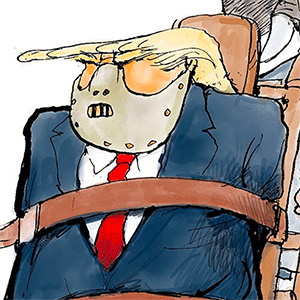

Jonathan Levin: Trump's tariff mistake isn't easily cured. Not even by the Supreme Court

Published in Op Eds

The Supreme Court’s decision that President Donald Trump illegally imposed tariffs on U.S. trading partners under the guise that America’s trade deficit amounts to a national emergency is a victory for the rule of law. As such, it’s also a win for the country’s reputation as a destination for global capital. Financial markets should celebrate — but not too much.

The 6-3 ruling is sure to spark volatility as businesses and investors adjust to yet another curveball from an already chaotic presidency. That’s because it’s possible the White House may attempt to reinstate the tariffs under different statutes. Meanwhile, the U.S. will have to reckon with a fresh hit to federal revenue when the budget deficit shows few signs of shrinking to a manageable level. In short, the court hasn’t managed to entirely nullify Trump’s egregious miscalculation of imposing the tariffs in the first place.

In its decision, the Supreme Court found that Trump exceeded his authority in imposing tariffs under the International Economic Emergency Powers Act, or IEEPA, the statute that the administration has relied upon to enact most of its sweeping new duties since April 2, 2025, or what the White House referred to as “Liberation Day.” The ruling also applies to the tariffs supposedly levied to curb fentanyl trafficking (which many observers viewed as a pretext).

From a legal standpoint, it always strained the imagination to understand how Trump could have used IEEPA — which is intended to counter foreign threats and never mentions the word “tariff” — as the justification for broad and unilateral duties on all trading partners, friends and foes alike.

What’s more, economists are in almost universal agreement that the policy hurts economic growth and contributes to higher consumer prices. In the long run, a Budget Lab at Yale analysis found that the economy would be persistently about 0.3 percentage point larger if the IEEPA tariffs go away (and aren’t immediately replaced). What’s more, the price-level increase from Trump’s tariffs costs households at the bottom of the income spectrum $1,900 annually. Although several other tariffs will stay in place, the hit theoretically falls to $642 by permanently invalidating the IEEPA duties, according to the Budget Lab.

The decision won’t completely offset a year of foolhardy policymaking. As far as companies are concerned, they will face continued questions about their supply chains, especially the small businesses that have been among the worst hit from the policy. Many will be stuck waiting to see whether the administration manages to replace IEEPA duties with similar ones under different statutes. At the very least, that will continue to delay investment decisions and restrain economic dynamism. As for consumers, it seems unlikely that companies will reverse price increases that have already taken place.

In financial markets, the bond market may suffer some indigestion as the government struggles to replace the hundreds of billions of dollars that had been penciled in from tariff revenue — let alone the money already collected to date that’s now potentially reimbursable to importers. (For now, it will be up to a lower court to work out the question of potential refunds to importers on the tariffs that were already paid.)

The Budget Lab found that tariff revenue from 2026-2035 was set to total around $2.4 trillion, and it would only be $704 billion with IEEPA invalidated. Tariffs were never going to be an efficient or sizable enough fix-all for America’s persistent fiscal deficits, but Republicans had used them to justify extending tax cuts to the wealthy last year. Without the duties, America’s fiscal outlook could be even worse than before. Yields on 10-year Treasury notes rose about 0.02 percentage point after the decision to 4.09%.

Gaming out what comes next is tricky. One path for the Trump administration could entail a combination of short- and medium-term tariff replacement options, as discussed in a recent Brookings commentary by Peter Shane and Robert Litan. For instance, in the immediate term, Trump could invoke Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974, which gives the president broad leeway to immediately levy tariffs of as much as 15% for 150 days. In the meantime, the administration could launch a series of trade-related investigations under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 or Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Though those procedures can be time-consuming, they can eventually lead to similar outcomes as the IEEPA tariffs. In the meantime, investors and businesses will be hamstrung by uncertainty.

There’s always the chance, however small, that Trump will take the “out” that the Supreme Court has given him and announce that he’s abandoning his ham-handed tariff strategy altogether. That would deliver some measure of relief to businesses and consumers, and it might actually end up helping his party in a midterm election year. I’m not betting on that level of pragmatism.

Certainly, it’s worth celebrating the fact that — at least in the case of IEEPA — checks and balances have effectively prevented a misuse of executive power. A wide body of evidence holds that strong institutional structures — in which power is shared and executive discretion is limited — lead to broad benefits for the country in question, including higher credit ratings and lower borrowing costs over time.

Yet none of that changes the fact that such sweeping tariffs never should have been issued by the president in the first place without Congress’ approval. Unfortunately, there will be a continuing economic price to pay.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jonathan Levin is a columnist focused on U.S. markets and economics. Previously, he worked as a Bloomberg journalist in the U.S., Brazil and Mexico. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments