In WA, thousands are forgoing health insurance this year. Here's why

Published in Business News

Ambrose Bittner, 63, didn’t want to go uninsured. But the self-employed travel planner has been without health coverage since the beginning of the year.

Bittner, who lives in Issaquah, is one of thousands of Washington state residents who decided to disenroll from health insurance, following the expiration of subsidies that helped millions of people afford high premiums.

At the start of open enrollment in November, Bittner logged on to the state insurance portal to look at future costs. He was already enrolled in the cheapest option available, a bronze plan with a monthly premium of $218. But without action from Congress, that plan was slated to jump to $800 per month for him in 2026.

“My premium was going to quadruple in price,” he said. “So I decided to forego insurance.”

For months, Washington lawmakers and local officials have been warning about potentially steep price hikes for people who buy their insurance with the help of subsidies, formally known as enhanced premium tax credits. Many projected that high premium increases would drive people to go uninsured.

As open enrollment closed on Jan. 15, early data is providing a glimpse at just how accurate those predictions were.

Compared to last year, new enrollment for 2026 dropped 17%. Meanwhile, 28,000 people actively canceled their coverage — a 38% increase, according to preliminary numbers shared with the Seattle Times by the Washington Health Benefit Exchange, which operates the state’s health insurance marketplace.

Taken together, that means there are significantly fewer people enrolled in individual plans right now compared to this time last year.

According to the exchange, there are 290,000 Washingtonians currently enrolled, a figure that includes new customers, existing ones who switched plans and those whose coverage was automatically renewed. At this point last year, a record-high 308,000 Washingtonians were enrolled.

State exchange officials emphasized that early enrollment figures are subject to fall further.

Every year, some segment of enrollees passively drops their coverage simply by not making their first or second premium payment.

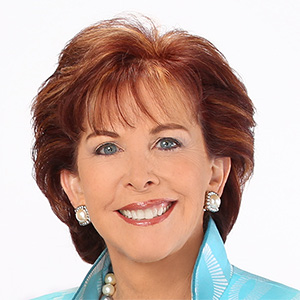

“We're only going to go downhill from here,” said Ingrid Ulrey, chief executive officer of the Washington Health Benefit Exchange, referring to the enrollment count for 2026. “That will decline as people actually receive their first bill.”

For instance, last year’s enrollment figures eventually fell from an early 308,000 to a final figure of 286,500 after accounting for people who passively canceled. Clearer enrollment data for 2026 won’t be available for another few months.

The state health insurance marketplace was established following the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which enabled people to buy their insurance through regulated exchanges.

Most people who buy insurance in the individual market do so because they don’t have traditional access to health coverage, such as through an employer or public programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

Such is the case for Bittner, who is the founder, owner and sole employee of Red Lantern Journeys, which designs customized travel tours. He’s been buying individual coverage since the establishment of the state health exchange, save for a few years during the COVID-19 pandemic when his income dipped low enough to qualify him for Medicaid.

The choice to cancel his coverage was a tough one.

With an anticipated income of around $100,000, Bittner technically could have afforded to pay $850 per month for coverage.

But Bittner considers himself relatively healthy. Even with insurance, the only times he went to the doctor were for preventive care and annual shots. Besides, he’ll be eligible for Medicare in about 15 months.

In the end, he decided that there were better ways to spend what would have amounted to more than $12,000 in premiums between now and then. “I’d rather retire more comfortably,” he said.

In the meantime, he has robust car insurance and travel insurance, both of which provide some emergency medical coverage in certain scenarios. For non-urgent matters, Bittner is willing to travel abroad for affordable treatment, which he’s done before.

Still, he said, “it’s certainly a risk. Things can happen.”

If Congress had come to a last-minute deal to extend the enhanced premium tax credits, he would have signed back up for coverage.

Local health care advocates are worried that this year’s drop in enrollment is a harbinger of higher premiums and uninsured rates to come.

There's a sense that we were beginning to round the corner on insurance access," said Emily Brice, co-executive director of advocacy for Northwest Health Law Advocates, a nonprofit that focuses on health care access.

The rate of Washingtonians without health insurance has dropped from 9.2% to 6.5% for the decade ending in 2024, according to most recent data available from the American Community Survey.

Brice is concerned that the state’s uninsured rate will rebound in the coming years, with ripple effects for health care providers and the wider economy.

Kyra Freestar, 51, a self-employed editor based in Seattle has long bought individual coverage through the state exchange. In 2024, she was eligible for the enhanced premium tax credits. After her income pushed her out of eligibility in 2025, she downgraded from a silver plan to a bronze plan to save money. This year, her premium for the same bronze plan was set to increase by 26% to around $740 per month.

Ultimately, Freestar decided to forego insurance altogether. Despite being expensive, Freestar said her previous bronze plan barely covered any of the treatments, specialist visits, supplements and screenings that she needs. She could pay for all her expected medical care out of pocket — it’ll cost between $400 to $500 a month — and still come out ahead.

"The idea that you can have insurance but not know what it will cover, it feels like insult on top of injury, she said.

Not everyone who disenrolls from the individual market will become uninsured, said Matt McGough, policy analyst at KFF, an organization that conducts research on the health care system. Some are small business owners and employees who decide to call it quits and find work at bigger companies that offer employer-provided insurance.

Short-term disenrollment could portend even higher premiums in the long run, McGough said.

When premiums rise, people who are relatively healthier tend to drop out of the market, leaving behind a riskier and more expensive pool of enrollees. To cover higher average costs, insurers then have to further increase premiums, which can push more people to drop out.

Early last year, state exchange officials projected that as many as 80,000 people in Washington would forego coverage due to the expiration of enhanced premium tax credits. Now, they’re expecting to see a smaller drop of around 40,000 instead — in part due to state-level cost assistance efforts aimed at mitigating disenrollment.

Ulrey, CEO of the Washington Health Benefit Exchange, expects that a final enrollment count for 2026 will be available in the spring.

©2026 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments