Unwinding Kellogg: Michigan corporate shakeout suffers latest loss

Published in Business News

Another corporate headquarters jilted Michigan recently when snack food maker Kellanova followed its Battle Creek cereal sibling, WK Kellogg Co., into the arms of a rival company two years after its spinoff chased growth in another city.

It's a familiar trend in Michigan now decades old. Venerable corporate names targeted by out-of-state industry competitors become the hunted, not the hunters, leaving company towns and the people in them pondering their futures and weighing their legacies.

Last year, Italian confectionery company Ferrero SpA bought WK Kellogg Co., jolting Battle Creek, its identity and corporate Michigan. Last month, Virginia-based Mars Inc., owner of Snickers, dog food brands and other nutrition options, closed its acquisition of now Chicago-based Kellanova, the parent of Cheez-It, Pringles and Pop-Tarts.

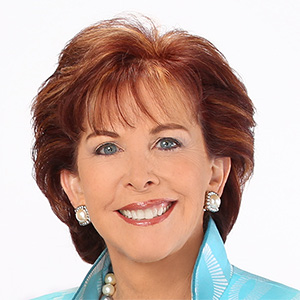

It was a "stunning achievement in terms of value creation,” former Kellanova CEO Steve Cahillane told Bloomberg, referring to the 2023 split and subsequent sale of both companies. Still, Battle Creek residents aren't so sure, and they think they have reasons to worry about the future.

“In the early years, they took care of their people,” said Jennifer Abrams, 55, of Battle Creek, who works in the medical field and whose grandfather worked 54 years for the company before retiring in plant maintenance. “That kind of loyalty, that’s all gone. You can see the decline in this town as they kept pulling from this town.

"I know people who work for the company. I feel sorry for them. Their jobs are unstable. There’s no security for anyone. They’re worried about their jobs, their insurance, their livelihood. We’re losing jobs around here like crazy. It would devastate the community if they move it.”

Battle Creek is synonymous with Kellogg, founded there on Feb. 19, 1906. Its name adorns institutions across town, from the community college and an arena to a $9.4 billion foundation originally capitalized in 1934 by a donation of Kellogg stock and investments. Decades of largesse by the company and foundation helped shape lives and culture, creating a familiar sense of expectation found not just in Battle Creek but in company towns across Michigan.

Kellogg Co.'s 2023 split into Kellanova and the WK Kellogg Co. and their sale to competitors aimed to maximize the value of their brands. Snack foods were growing, making them an attractive investment. Cereals were a mature market, drawing few resources for innovation. Splitting the iconic Kellogg Co. into two, the thinking went, would unlock shareholder value in snack foods and position cereals for investment to become more competitive.

"The industrial logic was easy to come to," Cahillane told the Executives' Club of Chicago last year. "The emotional impact of saying we're going to spin off Mr. Kellogg's business, what he started 118 years ago, was emotionally extraordinarily difficult. Some of the most tough moments were telling people things were going to change."

Yet they do, considering the steady devolution of corporate headquarters in Michigan. Household names like Kellogg, Chrysler and Steelcase exist as brands in their respective industries, but their decision-makers live and work elsewhere, even overseas, diminishing Michigan's historic claim to being one of the nation's Big Company states.

The unwinding of Kellogg is not isolated in corporate Michigan. In August, HNI Corp. in Muscatine, Iowa, said it would acquire Grand Rapids-based office furniture giant Steelcase Inc. in a $2.2 billion cash and stock deal that closed in December. And Comerica Inc., a historic cornerstone of corporate Michigan that moved its headquarters to Texas nearly two decades ago, fully surrendered itself to Cincinnati-based Fifth Third Bank. The deal set to close Feb. 1.

WK Kellogg, Kellanova and Steelcase declined requests for interviews on their acquisitions, though WK Kellogg and Kellanova responded to questions via email.

The WK Kellogg and Steelcase transactions are expected to leave regional or brand headquarters in Battle Creek and Grand Rapids, respectively. But the deals highlight a recurring phenomenon in corporate Michigan: the loss of global headquarters based in the state and the impact those losses can have on their communities. Think Upjohn pharmaceuticals in Kalamazoo; Chrysler Corp., since the late 1990s owned by Germans, Italians and now the French; and Kmart Corp., absorbed by Sears and steadily dismembered.

"Michigan’s middle-market companies are sometimes less growth-oriented than the out-of-state acquirers," said Erik Gordon, professor at the University of Michigan's Ross School of Business. "Our middle-market companies focus on doing a very good job of what they do. Nobody makes the kind of corporate furniture that Steelcase makes better than Steelcase makes it.

"But other companies are focused more on growing than our companies are. Companies can grow internally or do acquisitions. Our companies tend to have a down-to-Earth focus on doing what we do really well."

The decades-long disappearance of corporate headquarters in Michigan parallels trends in declining competitiveness that elude easy solutions: lagging educational achievement, slowing income gains and challenges with retraining workers and attracting talent. But if Michigan wants to be home to corporate headquarters and reap the benefits of leadership, prestige and professional jobs, experts say, consistently improving those metrics should be bipartisan and civic priorities.

"Headquarters matter enormously," said Lou Glazer, president of nonprofit Michigan Future Inc. "They are the highest-paying jobs and historically have been pretty stable. Enormously important is your knowledge base. It's the asset that matters most to headquarters. Michigan is lacking in college-educated adults."

Kellogg, rivals, deals

Kellogg Co. completed numerous acquisitions before the split. It bought Keebler Co. in 2001, later sold to Ferrero; purchased MorningStar Farms in 1999, which moved to Kellanova; acquired Kashi in 2000, which moved to WK Kellogg.

Before the spinoffs, Kellogg Co. believed Wall Street undervalued it. Snack foods, 80% of its revenues, represented a growing, high-margin business. But the Kellogg name, most recognizable as a cereal brand, was facing shifting consumer habits and needed to spend capital to modernize its plants and supply chains.

Pringles, Cheez-It and noodles were priority investments as the brands grew globally, leaving financial crumbs for the cereals business that formed the historic foundation of Kellogg.

"That crowded out every chance and every time we looked at what's it going to take to grow North America cereal," Cahillane said last year. "We had a conviction that North America cereal can grow, but not under our ownership, because we're always going to make a different choice."

People felt a deep emotional attachment to the business, Cahillane was reminded when the split was announced, and worried what the change would mean for the company’s legacy.

"There was a real grieving process, to be honest with you,” he told the Executives' Club of Chicago. "We had thousands of people to place in two different companies … and there was a real fear in the organization that this is going to mean thousands of job cuts.

"We didn’t announce any layoffs, and that was extraordinary," he continued. "There was a lot of cynicism that we wouldn't be able to do this."

Establishing a new identity, Kellanova opened a corporate headquarters on North Wells Street in Chicago, though it continues production in Battle Creek and plans to do so under Mars, a privately owned company, as well.

“As shared when the ... transaction was announced," Kellanova wrote in an email, "Battle Creek will remain a core location for the future Mars Snacking, including for R&D.” Through a spokesperson, Kellanova declined an interview request for Cahillane.

Mars announced its acquisition of Kellanova in August 2024. A filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reported Cahillane's merger-related compensation to be nearly $91 million, which included cash, potential value of accelerated stock vesting and cancellation or cash-out of unvested stock, other benefits and tax reimbursement.

WK Kellogg Co. said Ferrero approached the company after “seeing the progress we had made in just a short period of time as an independent public company. They share our excitement about the potential of the business as it enters the next chapter of its evolution.”

Kellanova's Cahillane is not alone in profiting from the deal. An SEC filing lists merger-related compensation for Gary Pilnick, WK Kellogg chairman and CEO, at close to $34 million, which included cash, potential value of payouts for stock and other benefits.

Kellogg said Battle Creek will remain a core location and will house Ferrero’s North America cereal headquarters, reinforcing what it called Ferrero’s community-first approach.

“Battle Creek isn’t just where we work — it’s been our home for nearly 120 years," the company said. "And we’re grateful to be part of an organization that believes in the community as strongly as we do. This effort includes a significant investment in our Battle Creek facility — which has been and will continue to be a critical part of our network.”

Battle Creek optimism

Joe Sobieralski sees hope.

The CEO of Battle Creek Unlimited, the local economic development agency, detects some excitement among WK Kellogg employees surrounding the move to a larger, privately held company like Ferrero. He said that's because the transaction, as well as the Mars-Kellanova tie-up consummated last month, differs from private equity takeovers.

"Private equity coming in and taking over and gutting it — it does not have that feel," he said.

Trevor Bidelman agreed. The fourth-generation WK Kellogg worker and union business agent said he was optimistic that private ownership could ease the pressures of Wall Street expectations, would bring a stronger commitment to cereals and put less focus on snacks.

Bidelman, 44, has worked for the company for 21 years. He started in 2004 in an on-call role. Later, he became a full-time production worker in the processing department and eventually completed the mechanical apprenticeship program to become a skilled mechanical technician.

He described the management style of previous ownership as top-down, but he was hopeful that Ferrero’s European roots would make management more collaborative: "I am optimistic that Ferrero's structure lends to it the ability to work together on making the plants as most profitable and as efficient as we can.

"What it's been told to us is that part of the reasons that Ferrero was interested in acquiring us was because of the Battle Creek heritage and how it started. They liked that part of the business. So that would mean to me that they would still want to have a presence in Battle Creek."

Kellogg’s involvement in the community has lessened over the years, said Battle Creek Mayor Mark Behnke. But there were growing concerns it could drop even further following the acquisition.

After meeting with other community and business leaders shortly after the announcement, Behnke said CEO Pilnick promised that nothing would change for at least one year — including no layoffs.

Behnke recently returned from a trip to Japan as part of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s first official investment mission for job retention: “Kellogg is known no matter where you go. People will say, 'Battle Creek, Michigan: Kellogg's in Battle Creek.' So, it's important, and it's interesting that the WK Kellogg cereal company will be a division of or a subsidiary of Ferrero company. They know that the Kellogg name will be on every box that they put together with their new organization.”

Still, some wonder if that identity could be lost: “There’s definitely a feeling of a little bit of anticipatory sadness that Battle Creek might not be as recognizable as now,” said Stacy Niemann, general manager of UpRoot Market & Eatery, a co-op grocery store in downtown Battle Creek. “That it may be turning into more of a global company, which has been in the works for a while. There’s fear about losing jobs and losing our place on the map if you will.”

Ferrero's acquisition of Kellogg closed shortly ahead of the market's grand opening in November, a years-long dream among a group of residents looking to revamp the food system. But it’s not the first transition for Battle Creek, and with health care, education and other downtown employers, Niemann remains optimistic.

“We’re all pretty determined," she said. "Battle Creek has a way about us that we’ll just come together and figure something out to make it work for all of us.”

'Never wanted change'

Still, analysts and policymakers say, the erosion of corporate headquarters in the state signals deeper issues in Michigan's competitiveness for investment and attracting talent.

The state's budget has made progress on infrastructure investments that businesses want to know the government will provide, said state Rep. Steve Frisbie, R-Pennfield Township outside Battle Creek. Work, however, still needs to be done on Michigan corporate and property taxes, regulatory obstacles and education — critical markers of competitiveness.

"We have to stay focused not on the names, but rather the outcomes," said Matt McCauley, Michigan Economic Development Corp.'s senior vice president of regional development. "And those outcomes are who within Michigan are investing in people, investing in places in such a way to build prosperity for Michigan? And that's who we want to do business with."

The state's colleges and universities draw people from all over the country — from the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, Grand Valley State University and Michigan Technological University to smaller institutions like Hillsdale College, said Patrick Anderson, CEO of the East Lansing-based Anderson Economic Group consultancy. Still, with just 35% of residents holding a four-year degree, Michigan trails the national average.

In K-12 education, Michigan lags, too. Over the past 30 years, the state fell to 44th from 16th in fourth grade reading, according to a report released last month by Business Leaders for Michigan, a statewide CEO group advocating a comprehensive strategy on education, business growth and talent retention. Seven of eight Michigan districts do worse than their peers in top states in math.

Professional service jobs that on average pay about 20% more have grown 35% nationally, but remained flat in Michigan for two decades. More ominously, Michigan — the state whose union-represented hourly workers helped build the American middle class — ranks 50th in household income growth over the past 25 years.

"Michigan has a very manufacturing-oriented economic development strategy," Glazer said. "That’s a completely different strategy than a headquarters strategy."

Ideally, a state is a haven for both, but it's a matter of what Michigan is prioritizing. And right now, that doesn't include an education system that sends enough students to college. Or making Michigan communities desirable places to live with public transit and walkable areas and encouraging headquarters to relocate to the state, Glazer said.

"Michigan is like the old man who used to be cool," said state Rep. Kristian Grant, D-Grand Rapids. "We put a lot of things in place when we were like the new, hip, right on the edge of things, and then we never wanted change anymore."

Michigan has innovators who so far remain headquartered in the state: Rocket Mortgage founder Dan Gilbert, United Wholesale Mortgage Holdings Corp. CEO Mat Ishbia and Dug Song, co-founder of Duo Security, Michigan's first tech unicorn.

"Unfortunately, a lot of states have frustrated their entrepreneurs and their pioneers," Anderson said. "Michigan was a state where the government policy seemed to encourage big unions. I do give Michigan leaders credit that over the last 20 years, they've recognized the role entrepreneurs play.

"Government policies during much of the lost decade that were focused on getting Google to get here and subsidizing GM and Ford and making labor peace with the UAW — all these are desirable, but none of them are long-term strategy. We need to be developing our newer industries and making use of the fact that we do have entrepreneurs here."

©2026 www.detroitnews.com. Visit at detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments