Column: The Eurovision Song Contest has lost its harmony

Published in Entertainment News

I used to think that the Eurovision Song Contest could give the European Union a lot of pointers. Inaugurated in 1956, making it more than twice as old as the EU, the competition has juggled cross-border enmities, voting machinations and the occasional war — in addition to music, smoke machines and choreography. For most of those seven decades, it’s self-corrected after scandals and controversies more nimbly than bureaucrats in Brussels can measure out red tape. Indeed, its broadly utopian vision of European, Mediterranean and trans-oceanic integration stands in contrast to that of the hapless EU.

But Eurovision has run out of bragging rights. Late last week, the broadcasters of four countries — Spain, Ireland, the Netherlands (with 14 wins among the trio) and Slovenia announced a boycott of the May 2026 competition in Vienna. They were joined this week by Iceland. The reason was the participation of Israel (a four-time winner since joining in 1973) amid its deadly occupation of Gaza. In the past, Eurovision resolved disputes by recalibrating the voting process that produces its Grand Final winner. That mechanism won’t be effective this time.

Over the decades, Eurovision has shifted from juries with one vote per judge, to weighted selections from panels, to public televoting (with up to 20 votes per caller) to the current 50/50 split between jurors and popular suffrage. Its often swift response to trouble helped allay grumbling over everything from the tiny clout of small countries to bloc-voting by former Soviet nations. It’s tweaked its rules to deal with misgivings about the effect of diaspora voters as well as to monitor other forms of cross-border collusion. An example of the last occurred in 2022, when the jury results of six countries were shunted on the live finals broadcast when a watchdog algorithm flagged them as suspicious.

This time, the European Broadcasting Union — the 113-member association of public broadcasters across some 50 nations that runs Eurovision — has once again reverted to election reform. It avoided a divisive vote on Israel’s participation, focusing the debate instead on a rule change to prevent the miasma that aggravated the 2025 results. According to an EBU investigation released in May, state entities helped promote Israel’s Eurovision 2025 entry, including digital ads placed on YouTube by the Israeli Government Advertising Agency (known as Lapam) encouraging callers to support singer Yuval Raphael with the 20-vote maximum permitted. Israel ended up winning the popular vote and placed second after national juries weighed in. Eurovision has always discouraged government-led campaigns, but it has no regulation outlawing political lobbying for a musical act.

To address this, the EBU is halving the maximum number of individual votes to 10 and will involve juries from the semifinal stage, not just in choosing the winner. While these changes don’t ban government lobbying, they diminish the potential effect of “mass mobilization.” Why didn’t the EBU choose to vote on suspending Israel? The technical reason is that, in this narrow case, the Israeli broadcaster was not in violation of EBU standards. That contrasts with it banning Russian television networks (which then quit Eurovision entirely) for parroting the Kremlin’s line on a much wider issue, the invasion of Ukraine. That was considered a violation of EBU insistence on the journalistic independence of member broadcasters. That maneuver to avoid debate over Gaza likely didn’t sit well with the five dissenters.

Their boycott, while passionate, will probably work itself out if and when there’s peace in Gaza — or what the five consider as such. Who knows how long that will take. In a message posted on social media, Eurovision director Martin Green said, “We know many fans want us to take a defined position on geo-political events. But the only way the Eurovision Song Contest can continue to bring people together is by ensuring we are guided by our rules first and foremost.”

In the meantime, will the competition continue to thrive? While Eurovision’s had internal spats before, Spain is one of the competition’s Big Five — a country usually given a bye into the Grand Final — and a source of substantial funding.

At the same time, politics is a major disincentive for musicians who just want to have fun (and promote their entertainment careers). “The political controversy makes what was once an honor feel more like a poisoned chalice,” says William Lee Adams, the founder of WiWibloggs, an independent Eurovision blog and YouTube channel. “I'm already hearing that some contestants may choose not to perform at Eurovision if they win at home. This creates a major PR crisis.” It will certainly affect the spirit of the feeder contests that are part of the Eurovision system, like the San Remo festival that helps pick Italy’s contestant and the Festival da Canção that does the same for Portugal.

Adams says there’s already a feeling of malaise among fans who are now “avoiding the toxic energy that has permeated what was once their happy place.” He expects viewership to decline this year because of the boycott. That may be ameliorated a bit because the EBU has apparently succeeded in wooing back Romania, Bulgaria and Moldava, which withdrew in recent years because their TV broadcasters couldn’t afford the cost of participation (each country pays an entry fee, but the amount is tailored to a nation’s budget). While audience numbers may drop, Adams says interest will remain high because of the controversies: “Viewers love a trainwreck, but it's a different story if you're on the train!”

———

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

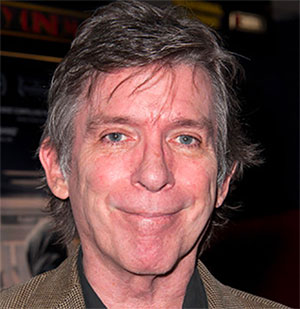

Howard Chua-Eoan is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion covering culture and business. He previously served as Bloomberg Opinion's international editor and is a former news director at Time magazine.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments