Native Americans have experienced a dramatic decline in life expectancy during the COVID-19 pandemic – but the drop has been in the making for generations

Published in Health & Fitness

Six and one-half years.

That’s the decline in life expectancy that the COVID-19 pandemic wrought upon American Indians and Alaska Natives, based on an August 2022 report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

This astounding figure translates to an overall drop in average living years from 71.8 years in 2019 to 65.2 by the end of 2021.

Although the pandemic is a major reason for this decline, it’s not the whole story. Even before COVID-19 emerged, life expectancy for Indigenous men was already five years lower than for non-Hispanic white men in the United States.

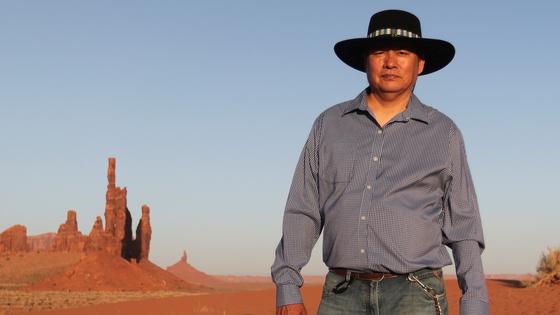

As a Native American physician and board-certified M.D., I am all too familiar with the health challenges that Indigenous Americans face.

Growing up in remote rural Alaska as a member of the Koyukon Athabascan tribe, I heard stories of how infectious diseases like flu, smallpox and tuberculosis threatened our survival. My cultural group descends from three families that survived the 1918 flu pandemic.

This history inspired me to become a traditional healer. Along with my training in Western medicine, I have also studied plant-based medicine and earth-based science, which was taught to me by my elders – practitioners who passed down thousands of years of accumulated knowledge to me.

Through both my medical and traditional practices, I have learned there are many reasons for the decline in life expectancy and the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health outcomes. But this gap – if the government and the medical system will act – can be narrowed.

American Indians and Alaska Natives die from diabetes at more than twice the rate of non-Indigenous populations. A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows Native Americans have significantly higher rates of obesity, high blood pressure, cancers and general poor health status than other Americans. The suicide rate in Indigenous communities is about 43% higher than that of non-Indigenous communities. And Native American women experience sexual violence far more often than non-Hispanic white women.

There are many reasons for these disparities. For starters: Native Americans have the highest poverty rate among all minority groups, perhaps as high as 25%.

Unemployment among American Indians and Alaska Natives in November 2022 was 6.2%, compared to 3.7% in the general population. Many Indigenous people, working only seasonally, are also woefully underemployed.

American Indians and Alaska Natives are also underserved in the U.S. health care system. The Indian Health Service – the federal agency that provides medical care to Indigenous Americans – is funded at about US$6 billion per year. That translated to only $4,078 per person in 2021.

The result is that there are fewer physicians, nurses and therapists seeing Indigenous patients, particularly those who live in rural areas. Those providing care have fewer technologies available to them, such as MRI and ultrasound machines, to help diagnose and treat disease earlier. Such shortages mean less access to either primary or emergency care, which contributes to lower life expectancy.

A shaky health care system is only part of the problem. Adverse childhood experiences, social marginalization and toxic, relentless stress also contribute to shorter lives.

Then there are the effects of unresolved historical trauma – the cumulative emotional and psychological trauma within a specific group that spans generations.

This kind of collective trauma cannot be overstated. A growing body of evidence is documenting its effects on Indigenous people. Historical trauma can produce physiological stress, striking not just individual people, but entire families. There is recent evidence to suggest that the body’s stress response has caused epigenetic changes – meaning changes in gene expression caused by the environment – in Native Americans that can affect one’s health even before birth.

To this day, the U.S. government has consistently created policies that sanctioned inequality – actions that have likely contributed to the historical trauma and health disparities present today. American Indian and Alaska Native communities have suffered from disease, war, internment and starvation for centuries.

Not only were Indigenous people displaced from the lands that were once our home, the U.S. government even made it illegal for us to practice their traditions. Throughout most of the 20th century, the U.S. government placed Indigenous children into boarding schools that separated them from their families.

It’s clear that Indigenous communities need new or upgraded hospitals and clinics, more and better diagnostic technology, more specialty services in dental care, obstetrics, pediatrics and oncology, and more alcohol and substance abuse treatment programs.

There is some good news: The Biden administration’s 2022 infrastructure bill makes $13 billion available to address some of these needs for Native American tribes. And an additional $20 billion appropriation for COVID-19 relief will also provide help for some of the most immediate challenges.

But even with this aid, there is still a funding gap. The National Indian Health Board, a nonprofit advocacy group representing federally recognized tribes, recommends a commitment of $48 billion for the 2024 fiscal year to fully fund the health needs of Indigenous people. The current budget, $9.3 billion, is less than one-fifth of that.

The recent increases in funding are certainly a step in the right direction. But the factors contributing to the shorter lives of Native Americans started generations ago, and they are still reverberating among the youngest of us today.

Both from a professional standpoint – as well as one that is very personal to me and my ancestors – more work in this area cannot come soon enough.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more:

Native Americans’ decadeslong struggle for control over sacred lands is making progress

Returning the ‘three sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures

Allison Kelliher receives funding from NSF EPSCoR and NIDA.

Comments