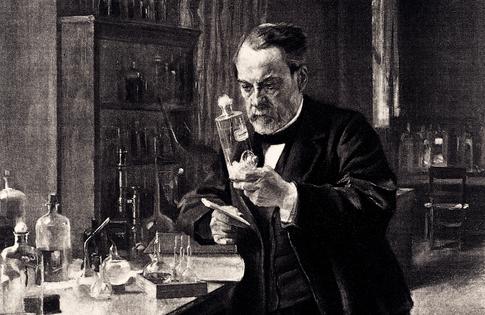

Louis Pasteur's scientific discoveries in the 19th century revolutionized medicine and continue to save the lives of millions today

Published in Health & Fitness

Some of the greatest scientific discoveries haven’t resulted in Nobel Prizes.

Louis Pasteur, who lived from 1822 to 1895, is arguably the world’s best-known microbiologist. He is widely credited for the germ theory of disease and for inventing the process of pasteurization – which is named after him – to preserve foods. Remarkably, he also developed the rabies and anthrax vaccines and made major contributions to combating cholera.

But because he died in 1895, six years before the first Nobel Prize was awarded, that prize isn’t on his resume. Had he lived in the era of Nobel Prizes, he would undoubtedly have been deserving of one for his work. Nobel Prizes, which are awarded in various fields, including physiology and medicine, are not given posthumously.

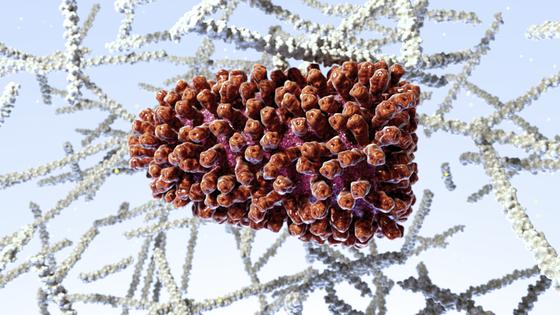

During the current time of ongoing threats from emerging or reemerging infectious diseases, from COVID-19 and polio to monkeypox and rabies, it is awe-inspiring to look back on Pasteur’s legacy. His efforts fundamentally changed how people view infectious diseases and how to fight them via vaccines.

I’ve worked in public health and medical laboratories specializing in viruses and other microbes, while training future medical laboratory scientists. My career started in virology with a front-row seat to rabies detection and surveillance and zoonotic agents, and it rests in large part on Pasteur’s pioneering work in microbiology, immunology and vaccinology.

In my assessment, Pasteur’s strongest contributions to science are his remarkable achievements in the field of medical microbiology and immunology. However, his story begins with chemistry.

Pasteur studied under the French chemist Jean-Baptiste-André Dumas. During that time, Pasteur became interested in the origins of life and worked in the field of polarized light and crystallography.

In 1848, just months after receiving his doctorate degree, Pasteur was studying the properties of crystals formed in the process of wine-making when he discovered that crystals occur in mirror-image forms, a property known as chirality. This discovery became the foundation of a subdiscipline of chemistry known as stereochemistry, which is the study of the spatial arrangement of atoms within molecules. This chirality, or handedness, of molecules was a “revolutionary hypothesis” at the time.

These findings led Pasteur to suspect what would later be proved through molecular biology: All life processes ultimately stem from the precise arrangement of atoms within biological molecules.

Beer and wine were critical to the economy of France and Italy in the 1800s. It was not uncommon during Pasteur’s life for products to spoil and become bitter or dangerous to drink. At the time, the scientific notion of “spontaneous generation” held that life can arise from nonliving matter, which was believed to be the culprit behind wine spoiling.

While many scientists tried to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation, in 1745, English biologist John Turberville Needham believed he had created the perfect experiment favoring spontaneous generation. Most scientists believed that heat killed life, so Needham created an experiment to show that microorganisms could grow on food, even after boiling. After boiling chicken broth, he placed it in a flask, heated it, then sealed it and waited, not realizing that air could make its way back into the flask prior to sealing. After some time, microorganisms grew, and Needham claimed victory.

However, his experiment had two major flaws. For one, the boiling time was not sufficient to kill all microbes. And importantly, his flasks allowed air to flow back in, which enabled microbial contamination.

To settle the scientific battle, the French Academy of Sciences sponsored a contest for the best experiment to prove or disprove spontaneous generation. Pasteur’s response to the contest was a series of experiments, including a prize-winning 1861 essay.

Pasteur deemed one of these experiments as “unassailable and decisive” because, unlike Needham, after he sterilized his cultures, he kept them free from contamination. By using his now famous swan-necked flasks, which had a long S-shaped neck, he allowed air to flow in while at the same time preventing falling particles from reaching the broth during heating. As a result, the flask remained free of growth for an extended period. This showed that if air was not allowed directly into his boiled infusions, then no “living microorganisms would appear, even after months of observation.” However, importantly, if dust was introduced, living microbes appeared.

Through that process, Pasteur not only refuted the theory of spontaneous generation, but he also demonstrated that microorganisms were everywhere. When he showed that food and wine spoiled because of contamination from invisible bacteria rather than from spontaneous generation, the modern germ theory of disease was born.

In the 1860s, when the silk industry was being devastated by two diseases that were infecting silkworms, Pasteur developed a clever process by which to examine silkworm eggs under a microscope and preserve those that were healthy. Much like his efforts with wine, he was able to apply his observations into industry methods, and he became something of a French hero.

Even with failing health from a severe stroke that left him partially paralyzed, Pasteur continued his work. In 1878, he succeeded in identifying and culturing the bacterium that caused the avian disease fowl cholera. He recognized that old bacterial cultures were no longer harmful and that chickens vaccinated with old cultures could survive exposure to wild strains of the bacteria. And his observation that surviving chickens excreted harmful bacteria helped establish an important concept now all too familiar in the age of COVID-19 – asymptomatic “healthy carriers” can still spread germs during outbreaks.

After bird cholera, Pasteur turned to the prevention of anthrax, a widespread plague of cattle and other animals caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Building on his own work and that of German physician Robert Koch, Pasteur developed the concept of the attenuated, or weakened, versions of microbes for use in vaccines.

In the late 1880s, he showed beyond any doubt that exposing cattle to a weakened form of anthrax vaccine could lead to what is now well known as immunity, dramatically reducing cattle mortality.

In my professional assessment of Louis Pasteur, the discovery of vaccination against rabies is the most important of all his achievements.

Rabies has been called the “world’s most diabolical virus,” spreading from animal to human via a bite.

Working with rabies virus is incredibly dangerous, as mortality approaches 100% once symptoms appear and without vaccination. Through astute observation, Pasteur discovered that drying out the spinal cords of dead rabid rabbits and monkeys resulted in a weakened form of rabies virus. Using that weakened version as a vaccine to gradually expose dogs to the rabies virus, Pasteur showed that he could effectively immunize the dogs against rabies.

Then, in July 1885, Joseph Meister, a 9-year-old boy from France, was severely bitten by a rabid dog. With Joseph facing almost certain death, his mother took him to Paris to see Pasteur because she had heard that he was working to develop a cure for rabies.

Pasteur took on the case, and alongside two physicians, he gave the boy a series of injections over several weeks. Joseph survived and Pasteur shocked the world with a cure for a universally lethal disease. This discovery opened the door to the widespread use of Pasteur’s rabies vaccine around 1885, which dramatically reduced rabies’ deaths in humans and animals.

Pasteur once famously said in a lecture, “In the fields of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind.”

Pasteur had a knack for applying his brilliant – and prepared – scientific mind to the most practical dilemmas faced by humankind.

While Louis Pasteur died prior to the initiation of the Nobel Prize, I would argue that his amazing lifetime of discovery and contribution to science in medicine, infectious diseases, vaccination, medical microbiology and immunology place him among the all-time greatest scientists.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Rodney E. Rohde, Texas State University. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

People will continue to die of rabies if Kenya doesn’t educate healthcare workers

Vaccinating domestic dogs reduces rabies in the wild. Why this matters

Rodney E. Rohde has received funding from the American Society of Clinical Pathologists (ASCP), American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science (ASCLS), U.S. Department of Labor (OSHA), and other public and private entities/foundations. Rohde is affiliated with ASCP, ASCLS, ASM, and serves on several scientific advisory boards. See https://rodneyerohde.wp.txstate.edu/service/.

Comments