Entertainment

/ArcaMax

19 Black historical figures you probably didn't learn about in class

For many years, school curricula have limited their scope to the same Black figures throughout history. While lectures on the legacies of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Harriet Tubman remain crucial, some educators and students are eager to learn about underrepresented trailblazers like Lewis Latimer, Marsha P. Johnson, and Max ...Read more

25 iconic TV shows that are so bad they're good

While we may have moved beyond the era of peak TV, there are still an overwhelming number of great shows to watch. A look at the September 2025 Emmy winners reveals several fantastic options, from buzzy new shows like "The Studio" and "The Pitt" to acclaimed ongoing series like "Hacks" and "Severance." But as satisfying as it is to sit down ...Read more

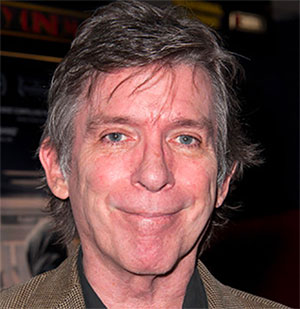

25 actors who quit or were fired from hit film franchises early on

Since the rise of Marvel movies in the 2000s, we've been living in the age of the cinematic universe. Sequels continue to dominate the box office, and the franchise is king. Without counting remakes, six of the 10 highest-grossing films of 2025 are continuations of previously existing IP. We can lament the fact that it's increasingly difficult ...Read more

Best West Coast small towns to live in

The American dream of buying a home in a quaint small town is alive and well. In 2023, more people moved to small towns than to cities, and the Census Bureau reported in 2024 that some of the fastest-growing communities in the country are considered exurban (i.e., well outside of major metropolitan areas).

Though 2023 marked the first year ...Read more

Best Midwest small towns to live in

When you look at 2025 and 2026 rankings of thebest places to live in America, thebest suburbs in America, or thebest small cities in America, you'll notice a recurring theme: the desirability of the Midwest. The region may be best known for big cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Indianapolis, but people are now turning their attention to the ...Read more