Column: Political giants and moral degenerates: My five best books of 2025

Published in Books News

The blame for America’s current troubles lies squarely with the Democratic establishment. Donald Trump’s re-election was always unlikely given his low approval ratings and divisive style. The Democratic establishment turned it into a certainty by: (1) running an aged and obviously ailing candidate (2) using its power over the press, almost a Democratic fief in the U.S., to close reporting on this obvious problem and (3) picking a second-rate vice president on the grounds that she ticked the right diversity boxes.

Different bits of the Democratic establishment were responsible for different bits of this disaster. The Biden family, particularly Jill Biden, together with Biden’s long-time consiglieri, bears responsibility for the first. The Democratic party-media complex bears responsibility for the second. And the party’s increasingly woke rank-and-file bears responsibility for the third.

"Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover Up, and His Disastrous Decision to Run Again," by CNN’s Jake Tapper and Axios’s Alex Thompson, tells the inside story of Biden’s doomed re-election bid and Harris’s disastrous aftermath in toe-curling detail. The authors demonstrate that Biden’s catastrophic debate performance did not drop from a clear blue sky. The president’s close advisors conspired to keep information about his deteriorating faculties, both mental and physical, from the public — and to some extent from Biden himself. How they imagined this doddering figure could have functioned as president in 2028 is hard to fathom.

The British equivalent of the Biden scandal was the Prince Andrew affair. Both involved public figures who were incapable of seeing themselves as the public saw them. Both turned on dramatic encounters with reality — Biden’s debate with Trump in June 2024 and Prince Andrew’s interview with Emily Maitlis in November 2019. And both inadvertently make the case that we need a new establishment. One difference is that Joe Biden still retains his name while Prince Andrew the Duke of York has now been downgraded into Andrew Mountbatten Windsor.

In "Entitled: The Rise and Fall of the House of York," Andrew Lownie, a literary agent and historian, provides us with hundreds of tidbits, big, small but always nauseating, of the Yorks’ appalling behavior, with his ex-wife Sarah Ferguson coming off almost as badly as her former husband and long-time housemate. The most disturbing revelations concern Windsor’s relations with Jeffrey Epstein that led to his downfall. Both Windsor and Ferguson continued to associate with Epstein long after he was convicted of pedophilia. But there are also hundreds of details about the pair’s money-grubbing and high-living ways, some of them what the British tabloids call “marmalade droppers.”

Both spent the past 50 years turning their royal titles and connections into cash, with no scheme too tawdry and no associates too dodgy. Ferguson was spendthrift to a pathological degree. Reading this book is rather like working your way through a box of Quality Street chocolates — you can’t resist gobbling down the next mouth-watering morsel, but you end up feeling thoroughly sick.

Sam Tanenhaus’s "Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America" is a long book but a thoroughly enjoyable one. Buckley is a big and varied enough subject to justify all the detail, a man who lived many lives rolled up in one: a conservative intellectual and a liberal society dandy, a professional writer and a world-class yachtsman, a champion debater and author of best-selling thrillers; and a one-time CIA agent to boot. There was never a dull moment in either his life or this book.

Buckley did as much as any single figure to forge the modern conservative movement — to take that whirlwind of rage at the liberal establishment that swelled in provincial America, the sunbelt and the suburbs and turn it into a coherent movement capable of shaping presidencies. He was the first U.S. conservative to identify the university — particularly his own university, Yale — as the headquarters of the liberal establishment. He was also the first to see that the various factions of the conservative movement — traditionalism, anti-Communism and free-market thinking — could be fused into one. The great work of the magazine that he founded in 1955, the National Review, was arranging and policing this fusion.

Previous biographers of Buckley have emphasized the way that he purified the conservative movement by driving out the cranks. Tanenhaus, a former editor of the New York Times book review, tells a more nuanced story: that Buckley always had a weakness for extremists, particularly extreme anti-Communists such as Joseph McCarthy and extreme Catholics such as his brother-in-law Brent Bozell, and therefore bears some of the responsibility for injecting ethnonationalism and theocracy into the conservative mix. The Buckley revolution may have come to fruition not in the Reagan presidency, as many conservative intellectuals have fondly argued, but in the Trump presidency.

America’s political turmoil, by turns colorful, hilarious and dispiriting, contrasts sharply with China’s disciplined march forward. Every year China seems to rack up new successes: more PhDs, more scientific publications, more nuclear warheads, better and cheaper electric cars. The contrast is partly explained by the fact that America has a free press, while China’s press is a party-boosting megaphone (though America’s free press failed us until it was too late in reporting on Biden’s failing health). But it is also explained by their different approaches to government.

In "Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future," Dan Wang, of Stanford’s Hoover institution, presents a gripping analysis of the difference between the two countries. China is an engineering state that sets itself firm goals and pursues them with dogged energy. The most visible signs of this engineering mindset are the physical miracles that you can encounter wherever you go across the country: spanking new airports and railway stations, high-speed trains that can carry you at 500 kilometers an hour, skyscrapers that disappear into the sky, all of which add up to a rising standard of living for regular Chinese people.

America is a society not just of laws but of lawyers. Its universities mass-produce lawyers with the same careless abandon that its car companies once mass-produced cars — more are always rolling down the production line. And the American political system, with its division of powers, multiple levels and multiple veto points, provides these lawyers with endless opportunities to throw spanners in the works.

Wang argues that each society would be better off if it learned from the other: China if it put more emphasis on individual rights, as encoded in law, and America if it kept lawyers on a tighter leash and got into the habit of building again. I suspect that neither thing will happen. The Chinese will extend their engineering mindset to social problems while America’s political polarization will further warp the legal system. Wang’s vision is nevertheless a comforting fantasy.

One of the many peculiarities of our age is that it is an age of strong men without great men. Trump is a weak man pretending to be a strong man: hence his limitless appetite for approval, even from dubious bodies such as FIFA, which awarded him its “Peace Prize” in lieu of the better-known Nobel Peace Prize, and his ever-shifting policy positions. Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping may qualify as strong men, if only because of their capacity for brutality, but they are far from great men: Putin, in particular, has trapped his country in a dead end of corruption and war-making.

"The Last Titans: Churchill and De Gaulle," by Richard Vinen, is a wonderful read because it focuses on two men who were everything today’s leaders are not: strong men who used their strength for good. Vinen, a professor of history at King’s College, London, demonstrates that Churchill and de Gaulle could hardly have been more different: Churchill was garrulous and attention-seeking while de Gaulle was given to long silences. De Gaulle spent months in his provincial home without speaking to anybody but his own family whereas Churchill was always surrounded by admirers, not to say sycophants even when he was trying to get away from it all in his country house, Chartwell,

But both men embodied everything that was best in their countries — and deliberately so. They prepared for power by soaking themselves in their countries’ history and literature. And when the moment came, they bent history in the direction of progress. Without Churchill, the West might have collapsed in 1940 and Germany overrun Europe. Without de Gaulle, France might have become a backwater. Reading this book leaves one optimistic and depressed at the same time: optimistic because it demonstrates that great men can change the direction of history, and depressed because we seem to have lost the ability to produce such giants.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

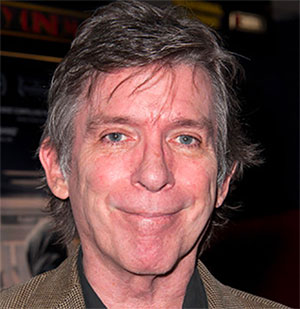

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former writer at the Economist, he is author of “The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments