Despite warning signs, Pennsylvania failed to take action in massive fraud case

Published in Business News

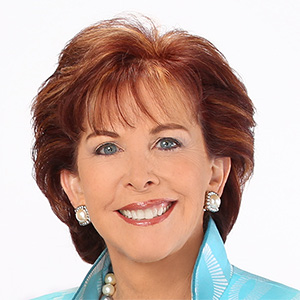

After weeks of investigating the inner workings of a giant investment company with ties to Pittsburgh, Toni Caiazzo Neff said she tried to do the right thing.

The former securities regulator had pored over the New York company's profit claims and mounting expenses.

She studied its purchases, including the acquisitions of car dealerships like the Kenny Ross Automotive Group, a signature brand in Pittsburgh for decades.

By the time she finished her inquiry into GPB Capital Holdings, she suspected the firm's leaders were orchestrating an enormous fraud that could impact thousands of investors across the country.

Alarmed, she said she picked up the phone in 2018 and called the lone state agency that specializes in investigating securities fraud: the Pennsylvania Department of Banking and Securities.

"There were red flags everywhere," said Ms. Neff, a Philadelphia-area resident who was working for a brokerage firm.

But the agency never took any action against GPB Capital, while its top executives continued to carry out a scheme that federal prosecutors say fleeced investors of more than $1.6 billion — one of the largest fraud cases of its kind in the last decade.

Not until federal agents and eight other state regulatory agencies launched their own investigations did the illegal operation come to an end in 2021, and company leaders were arrested.

The alerts sent to the Pennsylvania agency raise questions about the department's lack of enforcement at the time the scheme was ongoing and investors were continuing to purchase the private placement offerings, records and interviews show.

The information eventually led to the arrest of David Gentile, the 59-year-old founder who drove a Ferrari FF and traveled in private jets, for his role in what regulators called a Ponzi-like scheme that impacted more than 15,000 investors.

During his federal trial in 2024, prosecutors described the devastating impact the scam had on people, including retirees, veterans, teachers and farmers — some of whom lost their life savings.

"These were everyday Americans," said Ms. Neff. "These people lost everything."

The jury verdict against Gentile was celebrated by investors, but the punishment was overturned when President Donald Trump last year commuted the former executive's 7-year sentence just days after he reported to prison.

In late November, the White House announced that not only was Gentile freed, but he was no longer obligated to pay the $15.5 million in restitution mandated by the court, angering victims across the country.

Ms. Neff said the president's decision, which she called "outrageous," was the latest in a series of disappointments that began with her initial call to securities regulators in Harrisburg in July 2018.

She said she reached out to the state agency because she lived in Pennsylvania and she wanted to protect any investors in the commonwealth.

The company's claims that it could deliver guaranteed returns were highly questionable, she said, especially for the kinds of private placement investments that it offered through brokerages.

Combined with the company's expensive purchases, she said she was highly suspicious.

"The numbers didn't add up," she said.

Lavish lifestyles

Pennsylvania regulators could have taken a number of steps, from demanding more information from the company to launching a full investigation and issuing cease-and-desist orders to brokerages to stop selling GPB securities.

But ultimately, the agency — after exchanging phone calls and emails with Ms. Neff — never moved forward on the case.

"I was stunned," she said.

Ms. Neff, a former investigator with the National Association of Securities Dealers, said there were multiple reasons for the state to get involved.

Not only was she a state resident, but GPB Capital had purchased at least two businesses in Pennsylvania: Kenny Ross, with nine dealerships in the Pittsburgh area, and Iron City Express, a waste hauler in Crescent.

Image DescriptionPaul Marker, left, manager of Iron City Express, a waste hauler once owned by GPB Capital, chats with employee Matt Walker in the firms's new maintenance shop in Crescent Township on Friday, Dec. 12, 2025. (Steve Mellon/Post-Gazette)

Prosecutors say the car dealerships and waste company were used by GPB to prop up claims that it was reaping sizable profits and to keep the dollars flowing to investors between 2015 and 2018.

The company was actually failing to generate enough funds to cover its payouts and began siphoning money from new investors to fill in the shortfalls, while spending millions of dollars to support lavish lifestyles, prosecutors charged.

Gentile and another defendant, Jeffry Schneider, were also accused of funneling money through shell companies and collecting close to $2 million in fees for work they had already been paid for.

Though Pennsylvania regulators didn't take action, a host of other state securities agencies launched probes — including New York and New Jersey — eventually forming a task force and pressing enforcement actions starting in 2021 to recover money for investors in those states.

It's not clear how many of the company's investors lived in Pennsylvania, partly because the state did not initiate any enforcement actions that could have identified the number.

Contacted by the Post-Gazette, the Pennsylvania agency declined to answer questions about its decision regarding the investigation of the GPB case.

"Due to statutory, confidentiality requirements, the department is unable to discuss this issue," a spokeswoman wrote in an email.

Ms. Neff said that Pennsylvania regulators never explained to her why they didn't accept the case or join the other states in their task force.

Critical changes

At one time, Pennsylvania securities regulators were among the most aggressive in the country, say several legal experts interviewed by the Post-Gazette.

The state agency made a name for itself by lending some of its top investigators and accountants to national fraud cases that captured headlines.

That included agents who helped lead the 1990s investigation into Stratton Oakmont, a notorious brokerage firm known for pump-and-dump schemes that fleeced investors of hundreds of millions of dollars and later became the subject of the movie, The Wolf of Wall Street.

"Pennsylvania was one of the big five states doing [multi-state] fraud investigations when I was there," said Steven Irwin, who was a securities commissioner for the state for eight years, ending in 2014.

But in 2012, the department would undergo critical changes after Gov. Tom Corbett supported legislation merging the state's banking division in a shift that experts say resulted in the agency taking on fewer large-scale cases.

Overall, the number of enforcement actions between the two divisions dropped sharply in the last seven years, from 111 in 2019 to a low of 44 last year, records show.

Though the number of cases that focused specifically on securities enforcement increased since 2020 from 16 to 29 last year, many of those actions were centered on rudimentary violations like brokers not filing proper paperwork, according to the records.

At the time of the merger between the banking and securities agencies, Pennsylvania was facing a budget deficit of $4.2 billion, which forced state officials to look for ways to pare back spending, Mr. Corbett told the Post-Gazette.

"Both agencies did similar enforcement and we thought we could merge them and save some money," he said. "We had to get spending under control."

The goal, he said, was not to erode the securities department's ability to carry out fraud investigations.

"'Disappointment' is the word I would use because they should be doing those investigations," said Mr. Corbett, a Republican and former federal prosecutor who served as U.S. Attorney for the Western Pennsylvania under President George Bush. "It was never the intention to stop enforcement."

In an emailed response, a spokeswoman for the department stated that "a lower number of reported enforcement actions does not mean the Department is doing less to enforce the law. Enforcement totals can fluctuate year to year based on case complexity, timing, and coordination with other regulators."

She cited two cases where the state fined violators millions of dollars. Both cases were initiated nearly a decade ago in 2017 and were finalized in 2020 and 2022.

The spokeswoman said if other agencies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission had launched an investigation, the state, depending on the circumstances, may not initiate a parallel probe.

But several legal experts interviewed by the Post-Gazette say states like Pennsylvania are empowered to pursue such probes to recover damages on behalf of their own residents and can often alert statewide investors to stay away.

Nicholas Guiliano, a longtime Philadelphia securities attorney who has represented dozens of burned GPB investors, said the merger led to a lower profile for the agency.

"Pennsylvania has been markedly absent from most national cases over the last 10 years or so," he said.

Nowhere was that more apparent than in the GPB probe, when states as far away as Alabama joined in the sweeping investigation after Ms. Neff contacted them, she said.

"The more states that get involved, the more pressure it puts on those committing fraud, and the more it benefits investors who are the victims," said Lawrence Klayman, a South Florida securities attorney who represented investors in GPB. "The more help investors get from regulators, the better."

For Ms. Neff, that's what drove her to try to draw Pennsylvania regulators into the probe eight years ago.

"It's my home state. I felt obligated," she said. "I wanted to protect Pennsylvania investors. And I thought as a resident I'd be taken seriously. But it didn't happen."

©2026 PG Publishing Co. Visit at post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments