Warming winters are disrupting the hidden world of fungi – the result can shift mountain grasslands to scrub

Published in News & Features

When you look out across a snowy winter landscape, it might seem like nature is fast asleep. Yet, under the surface, tiny organisms are hard at work, consuming the previous year’s dead plant material and other organic matter.

These soil microorganisms – Earth’s recyclers – liberate nutrients that will act as fertilizer once grasses and other plants wake up with the spring snowmelt.

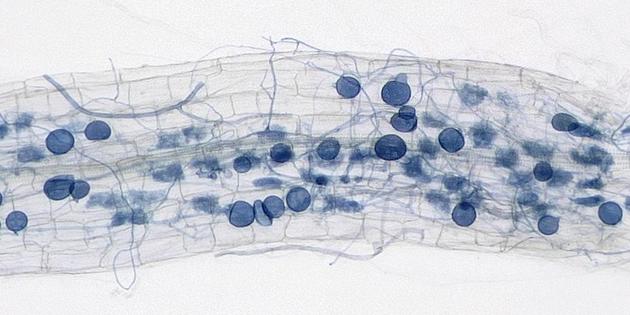

Key among them are arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, found in over 75% of plant species around the planet. These threadlike fungi grow like webs inside plant roots, where they provide up to 50% of the plant’s nutrient and water supply in exchange for plant carbon, which the fungi use to grow and reproduce.

In winter, the snowpack insulates mycorrhizal fungi and other microorganisms like a blanket, allowing them to continue to decompose soil organic matter, even when air temperatures above the snow are well below freezing. However, when rain washes out the snowpack or a healthy snowpack doesn’t form, water in the soil can later freeze – as can mycorrhizal fungi.

In a new study in the Rocky Mountain grasslands, we dug into plots of land that for three decades scientists led by ecologist John Harte had warmed by 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) using suspended heaters that mimicked the air temperature the area is likely to see by the end of this century.

Above ground, the plots shifted over that time from predominantly grassland to more desertlike shrublands. Under the surface, we found something else: There were noticeably fewer beneficial mycorrhizal fungi, which left plants less able to acquire nutrients or buffer themselves from environmental stressors like freezing temperatures and drought.

These changes represent a major shift in the ecosystem, one that, on a wide scale, could reverberate through the food web as the grasses and forbs, such as wildflowers, that cattle and wildlife rely on decline and are replaced by a more desertlike environment.

Warmer winters and a changing snowpack can affect the growth of plants and fungi in a few important ways.

One of the first signs of changing winters is when the timing of plant, fungal and animal activities that rely on one another get out of sync. For example, a mountain of evidence from around the world has documented how early snowmelt can lead to flowers blooming before pollinators arrive.

Timing also matters for plants that rely on mycorrhizal fungi – their growth must overlap.

Since plants are cued to light in addition to temperature, whereas underground microorganisms are cued to temperature and nutrient availability, warmer winters may cause microorganisms to be active well before their plant counterparts.

At our research site, in a subalpine meadow in Colorado, we also initiated an early snowmelt experiment in April 2023 that advanced snowmelt in five large plots by about two weeks.

We found that the early snowmelt advanced mycorrhizal fungal growth by one week, but we didn’t find a corresponding change in the growth of plant roots. When mycorrhizal fungi are active before plants, the plants don’t benefit from the nutrients that mycorrhizal fungi are taking up from the soil.

Early snowmelt can also lead to a loss of nutrients from the soil.

When microorganisms decompose organic matter in warmer soils, nutrients accumulate in the air and water pockets between soil particles. These nutrients are then available for mycorrhizal fungi to transfer to plants. While mycorrhizal fungi transfer nutrients to the plant, other fungi are primarily decomposers that keep the nutrients for themselves.

However, if rain falls on the snow or the snow melts early, before plants are active, the nutrients can leach from the soil into lakes and streams. The effect is similar to fertilizer runoff from farm fields – the nutrients fuel algae growth, which can create low-oxygen dead zones. At the same time, plants in the field have fewer nutrients available.

This kind of nutrient leaching has happened in a variety of ecosystems with warming winters and rain-on-snow events, ranging from mountain grasslands in Colorado to temperate forests in New England and the Midwest.

Without a thick snowpack, soils can also freeze for longer periods in the winter, leading to lower microbial activity and scarce resources at the onset of spring.

Under all of these scenarios – a timing mismatch, more rain causing nutrients to leach out or frozen soil – warmer winters are leading to less spring growth.

Ecosystems are often resilient, however. Organisms could acclimate to lower nutrient concentrations or shift their ranges to more favorable conditions. How plants and mycorrhizal fungi both adapt will determine how this hidden world adjusts to changing winters.

So, the next time rain on snow or a snow drought delays your outdoor winter plans, remember that it’s more than a hassle for humans – it’s affecting that hidden world below, with potentially long-term effects.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Stephanie Kivlin, University of Tennessee; Aimee Classen, University of Michigan, and Lara A. Souza, University of Oklahoma

Read more:

The golden oyster mushroom craze unleashed an invasive species – and a worrying new study shows it’s harming native fungi

Beyond flora and fauna: Why it’s time to include fungi in global conservation goals

Colorado’s subalpine wetlands may be producing a toxic form of mercury – that’s a concern for downstream water supplies

Stephanie Kivlin received funding from NSF Award #2338421, #1936195 and DOE Award #DE-FOA-0002392. She is an associate professor in the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory.

Aimee Classen receives funding from the US Department of Energy and the US National Science Foundation. She is a professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan and the director of the University of Michigan Biological Station.

Lara A. Souza received funding from National Science Foundation and The United States Department of Agriculture. She is affiliated with The University of Oklahoma, Norman and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory.

Comments