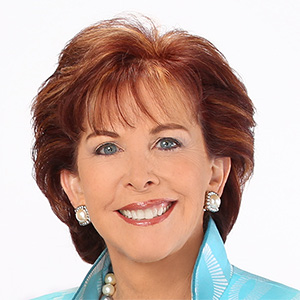

Catherine Thorbecke: Chinese AI videos used to look fake. Now they look like money

Published in Business News

Even six months ago, artificial intelligence-generated videos still betrayed themselves, with extra fingers, jerky limbs and uncanny facial expressions. While some of that persists, for the most part, we’ve entered an era where seeing is no longer believing.

It isn’t just the quality that has changed. In China, AI video is doing something else that once looked unlikely: making money. While attention remains fixed on the race to build massive foundation models like DeepSeek’s, the real contest is shifting to AI products that people will pay for and the search for a killer AI app. Early evidence from Kuaishou Technology suggests the winner may not be a chatbot at all, but a video tool.

Long the underdog to ByteDance’s Douyin, Kuaishou has spent the past year recasting itself as an AI video contender with global ambitions. Its Kling AI platform currently has the top spot on the video “quality” ranking from Artificial Analysis. And most significantly, it’s gaining traction not just at home but in the more lucrative overseas markets.

A December update dubbed “motion control,” which more accurately transfers movement from a reference video into a generated clip, went viral, for better or worse, as people digested the obvious misuse cases. Since then, monthly active users for Kling rose 110% from 3 million in December to 7.7 million in January, according to market intelligence firm Sensor Tower. Separate figures cited by domestic business outlet LatePost indicate that paying users surged 350% month-over-month in January. Investors have noticed, sending shares up more than 75% in the past year.

The company said Kling’s annualized revenue run rate, or monthly operating revenue times 12, hit $240 million in December. That’s striking in an arena still dominated by free products — and a timely reminder that monetization is starting to surface in the product layer, not the foundation model itself. Users are hungry for AI applications that go beyond just chatting. And the revenue wasn’t all domestic: 29% last year came from China, while 26% was from the U.S., according to Sensor Tower.

Still, none of this guarantees staying power. Novelty is cheap in AI and competition relentless. Nearly every major domestic player — as well as Silicon Valley titans — now ship some form of video generator, and Vidu, from Beijing-based Shengshu Technologies currently outranks Kling on Artificial Analysis’ text-to-video leaderboard. Viral moments don’t guarantee durable growth, and the internet has a remarkably short attention span. OpenAI’s much-hyped Sora app, an AI-generated TikTok clone, seemed to recede from the mainstream as fast as it arrived.

I found Kling’s appeal obvious because the output is dangerously “good enough.” In minutes, I created a realistic five-second clip of Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi dancing — the kind of low-effort, high believability content that makes regulators sweat. I also turned images of real people I know into videos with unsettling ease. And with a two-line prompt, I generated a Studio Ghibli-like animated scene for less time than it took to reboot my laptop.

One strategic lesson from Kling’s breakout success is focus. Kuaishou didn’t charge headfirst into the war of a hundred foundation models. It leaned on the troves of visual data from its short-form app to build a specific product, and then targeted user bases with budgets. Professional and enterprise clients account for 70% of total revenue, the company told the South China Morning Post. At a time when paying AI users can be fickle, and Chinese consumers even more so, that mix is the closest thing the sector has to a moat.

Even with money coming in, costs remain high. In January, the company sold bonds to bolster its AI funding, tapping offshore markets for the first time. It’s a reminder that inference, or deploying AI products, isn’t cheap.

Which is precisely why the smartest AI video players are courting corporate clients, not just content creators. Coca-Cola Co. has now run AI-generated holiday ads two years in a row. The backlash was loud in certain corners of the internet, but consumers ultimately didn’t seem to mind. For advertisers, AI tools like this promise faster production, lower costs and infinite iteration. The fear that AI will hollow out creative work is not misplaced. But if there’s going to be a public uprising, it probably won’t start with the art of selling sugary beverages.

But it may emerge from artists creating the characters people actually love. When I scrolled through the app, I found a carousel of familiar intellectual property, from Barbie to Pikachu, remixed into new creations and widely shared. As Chinese-origin apps scale abroad, outsize scrutiny is guaranteed. Add video, with its built-in potential for deepfakes, fraud and manipulation, and regulators likely won’t be entertained by these tools for too long. Kuaishou would be wise to invest heavily in internal guardrails for copyright protection and potential abuse before being forced to do so.

AI video used to just look fake. Now it looks like a business model. The challenge is that the better Kling gets, the harder it will be for regulators to leave it alone.

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments