Business

/ArcaMax

Real estate Q&A: Can HOA make me take down holiday decorations?

Q: I live in a homeowners’ association, and I decorated my house and yard for the holidays. They made me take it down under threat of a fine. Are they allowed to do this? – Gunther

A: Living in a community association means following a set of rules and regulations you agreed to when you purchased your home. These rules often govern how you ...Read more

How artificial intelligence became real estate's new secret weapon

CRANBERRY TOWNSHIP, Pennsylvania — Coldwell Banker agent Georgie Smigel used to spend hours digging through spreadsheets and old inquiry lists trying to figure out who might be interested in a new listing.

Now she simply asks her artificial intelligence software who is looking for a $250,000 house in a given Pittsburgh neighborhood or suburb....Read more

These are the Seattle area's Gen Z homeowners. How did they do it?

If you picture a first-time homebuyer in the Seattle area, you probably wouldn’t think of 24-year-old Edwin Nino Delgado with his hip-hop posters taped to the wall of his $770,000 Lake City triplex.

He’s nowhere near the age of the typical first-time homebuyer, which is now a record high of 40 nationwide, according to the National Realtors ...Read more

Gen Zers, just because you can buy a home, should you?

Just because you can buy a home, should you?

It seems like a no-brainer when home prices soar year after year. But experts say first-time homebuyers need to consider factors beyond pure capital before jumping into the market.

The median age of a first-time homebuyer has reached a record high of 40 — a time when most people are settled. But ...Read more

Pentagon to pay Boeing $8.6B to make fighters for Israel, raising concerns

Boeing will design and produce 25 new fighter jets for the Israeli Air Force under a new contract with the U.S. Department of Defense, reigniting concern about the aerospace manufacturer’s connection to the ongoing violence in Gaza.

The Pentagon said Monday it had awarded Boeing an $8.6 billion contract to build and deliver 25 new F-15IA ...Read more

Pa. hemp industry buffeted by lack of framework and controversial new rules

HARRISBURG, Pennsylvania — When the federal government gave hemp-growing the green light in 2018, Josh Bobbert almost literally bet the farm on the crop, figuring the versatile plant was going to be a moneymaker for himself, his wife, and nine children.

Since then, though, devoting a lot of his 61-acre family farm in Lawrence County, ...Read more

Southern California's unlikely AI mecca is this very industrial city

Five miles south of downtown Los Angeles, a single industrial block in Vernon is drawing as much electricity as a small town.

Inside a three-story, 242,000-square-foot building known as LAX01, rows of advanced artificial intelligence chips hum across six data buildings, consuming enough electricity to power more than 26,400 homes for a year. ...Read more

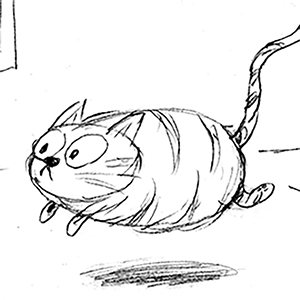

Tucked away in a downtown Chicago office building, fallen e-commerce star Groupon is ready for a comeback

Inside Groupon’s 2-year-old headquarters on the 25th floor of the Leo Burnett Building in downtown Chicago, a giant cat in a spaceship with flashing lights greets visitors in an otherwise staid office tower.

Here, the quirky e-commerce startup once dubbed the fastest-growing company ever, amid Super Bowl ads and ubiquitous media coverage, is ...Read more

How a family of Black entrepreneurs has changed a Miami Starbucks

MIAMI — There was a buzz in the air at a Starbucks near the downtown Miami Brightline station — and it wasn’t only because of the caffeine.

A “Holiday Sip and Shine,” featuring kids’ games, a DJ and drink specials, took over the cafe.

Concessions International, a Black-owned business, operates this Starbucks, and wanted local ...Read more

Let's talk about heat pumps: This Pittsburgh utility is helping to train contractors on the science and art of HVAC

PITTSBURGH — Frank Gillis laid out four sheets of fiberglass inside the Penn College Building Performance Lab in Pittsburgh's Homewood neighborhood.

With a knife, he demonstrated how to cut through the insulation layer, stopping short of the aluminum cover — "like filleting a fish" — and how to fold the sheet into a rectangular duct, ...Read more

Conor Sen: The housing market is moving in favor of Gen Z

The American dream of owning a home has never seemed further out of reach for young people. You can hardly blame Gen Z and younger millennials for adopting an economic nihilism that prioritizes the here and now — whether that’s $400 Lola blankets or risky crypto trading — over stashing money away for a down payment.

But there’s an ...Read more

Ford at odds with Sen. Ted Cruz over January affordability hearing

WASHINGTON — A standoff has developed between U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz and the Detroit Three automakers over executives' attendance at a planned hearing next month on vehicle affordability.

The Texas Republican last month invited the heads of Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and Chrysler parent company Stellantis NV to testify Jan. 14 in front of...Read more

With launch day nearing, all eyes on Minnesota's new paid leave program

Minnesota will start the new year with a paid leave law that took years to implement, launching a new benefit — and a new tax — for workers and employers.

Political stakes are high for the success of the program, which a DFL-controlled Legislature passed and Gov. Tim Walz signed into law with a host of other progressive policies in 2023.

...Read more

Neiman Marcus parent sells its Beverly Hills site

LOS ANGELES — The land below the Beverly Hills flagship store of luxury retailer Neiman Marcus has been sold to a New York investor as the owners of the department store chain sell property to pay debts.

Neiman Marcus, which has occupied the 9700 Wilshire Boulevard store since it opened in 1979, will continue to serve customers there as a ...Read more

Meet the 'rockstar CEO' leading Bay Area's unprecedented Super Bowl-World Cup back-to-back

Zaileen Janmohamed hardly had time to update her LinkedIn profile when she received her first and only marching orders from her new boss, Al Guido, the San Francisco 49ers president and board member of the newly formed Bay Area Host Committee.

Go get us Super Bowl 60.

Ten weeks later, the short, spunky Canadian of Indian descent and mother of...Read more

Alaska Air's year of expansion will bring the world closer to Seattle

Last December, Alaska Air Group executive Ryan St. John said the SeaTac-headquartered airline had reached an “inflection point” in its 90-plus-year history.

Alaska had recently completed its $1.9 billion acquisition of Hawaiian Airlines, the second time the company had bought another mainline air carrier in less than a decade. With the ...Read more

After a rough 2025, Las Vegas gaming and tourism should have a mixed '26

LAS VEGAS — For the gaming and tourism industries, news will be a mixed bag coming up in 2026.

The construction outlook is weak — but the city could still have its best convention year in history.

Air passenger traffic is down — but Harry Reid International Airport officials are still planning ahead for more airport gates as well its ...Read more

How California's Delete Act will protect personal information from data brokers in the New Year

Use a loyalty card at a drug store, browse the web, post on social media, get married or do anything else most people do, and chances are companies called data brokers know about it — along with your email address, your phone number, where you live and virtually everywhere you go.

But starting Jan. 1, under California's first-in-the-nation ...Read more

Telluride remains closed to skiing with patrollers on strike

Telluride Ski Resort remained closed on Monday, as its ski patrollers spent their third day on strike.

The union, known as the Telluride Professional Ski Patrol Association, walked off the job on Saturday — during the busy holiday tourist season — following months of negotiations with the resort ownership over a new contract. The patrollers...Read more

Mortgage rates could drop below 6% in 2026, report says

Mortgage rates could briefly drop below 6 percent in 2026 which could unlock parts of the Las Vegas Valley housing market, according to a new forecast.

Lending Tree’s 2026 Housing and Economic Predictions report expects mortgage rates to drop into the 5 percent range sometime next year, something that has not happened since 2022. Freddie Mac ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Ford at odds with Sen. Ted Cruz over January affordability hearing

- With launch day nearing, all eyes on Minnesota's new paid leave program

- Tucked away in a downtown Chicago office building, fallen e-commerce star Groupon is ready for a comeback

- How a family of Black entrepreneurs has changed a Miami Starbucks

- These are the Seattle area's Gen Z homeowners. How did they do it?