Ada Lovelace's skills with language, music and needlepoint contributed to her pioneering work in computing

Published in Science & Technology News

Ada Lovelace, known as the first computer programmer, was born on Dec. 10, 1815, more than a century before digital electronic computers were developed.

Lovelace has been hailed as a model for girls in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). A dozen biographies for young audiences were published for the 200th anniversary of her birth in 2015. And in 2018, The New York Times added hers as one of the first “missing obituaries” of women at the rise of the #MeToo movement.

But Lovelace – properly Ada King, Countess of Lovelace after her marriage – drew on many different fields for her innovative work, including languages, music and needlecraft, in addition to mathematical logic. Recognizing that her well-rounded education enabled her to accomplish work that was well ahead of her time, she can be a model for all students, not just girls.

Lovelace was the daughter of the scandal-ridden romantic poet George Gordon Byron, aka Lord Byron, and his highly educated and strictly religious wife Anne Isabella Noel Byron, known as Lady Byron. Lovelace’s parents separated shortly after her birth. At a time when women were not allowed to own property and had few legal rights, her mother managed to secure custody of her daughter.

Growing up in a privileged aristocratic family, Lovelace was educated by home tutors, as was common for girls like her. She received lessons in French and Italian, music and in suitable handicrafts such as embroidery. Less common for a girl in her time, she also studied math. Lovelace continued to work with math tutors into her adult life, and she eventually corresponded with mathematician and logician Augustus De Morgan at London University about symbolic logic.

Lovelace drew on all of these lessons when she wrote her computer program – in reality, it was a set of instructions for a mechanical calculator that had been built only in parts.

The computer in question was the Analytical Engine designed by mathematician, philosopher and inventor Charles Babbage. Lovelace had met Babbage when she was introduced to London society. The two related to each other over their shared love for mathematics and fascination for mechanical calculation. By the early 1840s, Babbage had won and lost government funding for a mathematical calculator, fallen out with the skilled craftsman building the precision parts for his machine, and was close to giving up on his project. At this point, Lovelace stepped in as an advocate.

To make Babbage’s calculator known to a British audience, Lovelace proposed to translate into English an article that described the Analytical Engine. The article was written in French by the Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea and published in a Swiss journal. Scholars believe that Babbage encouraged her to add notes of her own.

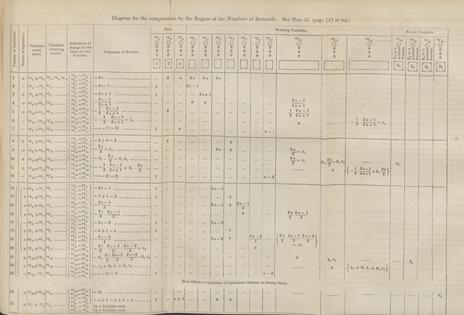

In her notes, which ended up twice as long as the original article, Lovelace drew on different areas of her education. Lovelace began by describing how to code instructions onto cards with punched holes, like those used for the Jacquard weaving loom, a device patented in 1804 that used punch cards to automate weaving patterns in fabric.

Having learned embroidery herself, Lovelace was familiar with the repetitive patterns used for handicrafts. Similarly repetitive steps were needed for mathematical calculations. To avoid duplicating cards for repetitive steps, Lovelace used loops, nested loops and conditional testing in her program instructions.

The notes included instructions on how to calculate Bernoulli numbers, which Lovelace knew from her training to be important in the study of mathematics. Her program showed that the Analytical Engine was capable of performing original calculations that had not yet been performed manually. At the same time, Lovelace noted that the machine could only follow instructions and not “originate anything.”

Finally, Lovelace recognized that the numbers manipulated by the Analytical Engine could be seen as other types of symbols, such as musical notes. An accomplished singer and pianist, Lovelace was familiar with musical notation symbols representing aspects of musical performance such as pitch and duration, and she had manipulated logical symbols in her correspondence with De Morgan. It was not a large step for her to realize that the Analytical Engine could process symbols — not just crunch numbers — and even compose music.

Inventing computer programming was not the first time Lovelace brought her knowledge from different areas to bear on a new subject. For example, as a young girl, she was fascinated with flying machines. Bringing together biology, mechanics and poetry, she asked her mother for anatomical books to study the function of bird wings. She built and experimented with wings, and in her letters, she metaphorically expressed her longing for her mother in the language of flying.

Despite her talents in logic and math, Lovelace didn’t pursue a scientific career. She was independently wealthy and never earned money from her scientific pursuits. This was common, however, at a time when freedom – including financial independence – was equated with the capability to impartially conduct scientific experiments. In addition, Lovelace devoted just over a year to her only publication, the translation of and notes on Menabrea’s paper about the Analytical Engine. Otherwise, in her life cut short by cancer at age 37, she vacillated between math, music, her mother’s demands, care for her own three children, and eventually a passion for gambling. Lovelace thus may not be an obvious model as a female scientist for girls today.

However, I find Lovelace’s way of drawing on her well-rounded education to solve difficult problems inspirational. True, she lived in an age before scientific specialization. Even Babbage was a polymath who worked in mathematical calculation and mechanical innovation. He also published a treatise on industrial manufacturing and another on religious questions of creationism.

But Lovelace applied knowledge from what we today think of as disparate fields in the sciences, arts and the humanities. A well-rounded thinker, she created solutions that were well ahead of her time.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Corinna Schlombs, Rochester Institute of Technology. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

Leonardo joined art with engineering

Why science and engineering need to remind students of forgotten lessons from history

Corinna Schlombs does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments