Climate change is shifting the zones where plants grow – here’s what that could mean for your garden

Published in Science & Technology News

With the arrival of spring in North America, many people are gravitating to the gardening and landscaping section of home improvement stores, where displays are overstocked with eye-catching seed packs and benches are filled with potted annuals and perennials.

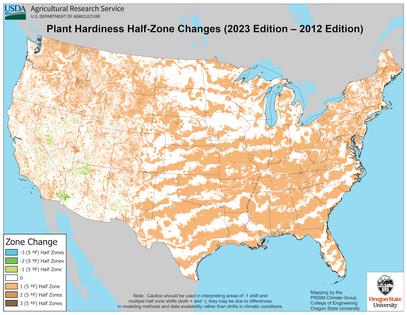

But some plants that once thrived in your yard may not flourish there now. To understand why, look to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s recent update of its plant hardiness zone map, which has long helped gardeners and growers figure out which plants are most likely to thrive in a given location.

Comparing the 2023 map to the previous version from 2012 clearly shows that as climate change warms the Earth, plant hardiness zones are shifting northward. On average, the coldest days of winter in our current climate, based on temperature records from 1991 through 2020, are 5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 Celsius) warmer than they were between 1976 and 2005.

In some areas, including the central Appalachians, northern New England and north central Idaho, winter temperatures have warmed by 1.5 hardiness zones – 15 degrees F (8.3 C) – over the same 30-year window. This warming changes the zones in which plants, whether annual or perennial, will ultimately succeed in a climate on the move.

As a plant pathologist, I have devoted my career to understanding and addressing plant health issues. Many stresses not only shorten the lives of plants, but also affect their growth and productivity.

I am also a gardener who has seen firsthand how warming temperatures, pests and disease affect my annual harvest. By understanding climate change impacts on plant communities, you can help your garden reach its full potential in a warming world.

There’s no question that the temperature trend is upward. From 2014 through 2023, the world experienced the 10 hottest summers ever recorded in 174 years of climate data. Just a few months of sweltering, unrelenting heat can significantly affect plant health, especially cool-season garden crops like broccoli, carrots, radishes and kale.

Winters are also warming, and this matters for plants. The USDA defines plant hardiness zones based on the coldest average annual temperature in winter at a given location. Each zone represents a 10-degree F range, with zones numbered from 1 (coldest) to 13 (warmest). Zones are divided into 5-degree F half zones, which are lettered “a” (northern) or “b” (southern).

For example, the coldest hardiness zone in the lower 48 states on the new map, 3a, covers small pockets in the northernmost parts of Minnesota and has winter extreme temperatures of -40 F to -35 F. The warmest zone, 11b, is in Key West, Florida, where the coldest annual lows range from 45 F to 50 F.

On the 2012 map, northern Minnesota had a much more extensive and continuous zone 3a. North Dakota also had areas designated in this same zone, but those regions now have shifted completely into Canada. Zone 10b once covered the southern tip of mainland Florida, including Miami and Fort Lauderdale, but has now been pushed northward by a rapidly encroaching zone 11a.

Many people buy seeds or seedlings without thinking about hardiness zones, planting dates or disease risks. But when plants have to contend with temperature shifts, heat stress and disease, they will eventually struggle to survive in areas where they once thrived.

Successful gardening is still possible, though. Here are some things to consider before you plant:

Hardiness zones matter far less for annual plants, which germinate, flower and die in a single growing season, than for perennial plants that last for several years. Annuals typically avoid the lethal winter temperatures that define plant hardiness zones.

In fact, most annual seed packs don’t even list the plants’ hardiness zones. Instead, they provide sowing date guidelines by geographic region. It’s still important to follow those dates, which help ensure that frost-tender crops are not planted too early and that cool-season crops are not harvested too late in the year.

Many perennials can grow across wide temperature ranges. For example, hardy fig and hardy kiwifruit grow well in zones 4-8, an area that includes most of the Northeast, Midwest and Plains states. Raspberries are hardy in zones 3-9, and blackberries are hardy in zones 5-9. This eliminates a lot of guesswork for most gardeners, since a majority of U.S. states are dominated by two or more of these zones.

Nevertheless, it’s important to pay attention to plant tags to avoid selecting a variety or cultivar with a restricted hardiness zone over another with greater flexibility. Also, pay attention to instructions about proper sun exposure and planting dates after the last frost in your area.

Fruit trees have two parts, the rootstock and the scion wood, that are grafted together to form a single tree. Rootstocks, which consist mainly of a root system, determine the tree’s size, timing of flowering and tolerance of soil-dwelling pests and pathogens. Scion wood, which supports the flowers and fruit, determines the fruit variety.

Most commercially available fruit trees can tolerate a wide range of hardiness zones. However, stone fruits like peaches, plums and cherries are more sensitive to temperature fluctuations within those zones – particularly abrupt swings in winter temperatures that create unpredictable freeze-thaw events.

These seesaw weather episodes affect all types of fruit trees, but stone fruits appear to be more susceptible, possibly because they flower earlier in spring, have fewer hardy rootstock options, or have bark characteristics that make them more vulnerable to winter injury.

Perennial plants’ hardiness increases through the seasons in a process called hardening off, which conditions them for harsher temperatures, moisture loss in sun and wind, and full sun exposure. But a too-sudden autumn temperature drop can cause plants to die back in winter, an event known as winter kill. Similarly, a sudden spring temperature spike can lead to premature flowering and subsequent frost kill.

Plants aren’t the only organisms constrained by temperature. With milder winters, southern insect pests and plant pathogens are expanding their ranges northward.

One example is Southern blight, a stem and root rot disease that affects 500 plant species and is caused by a fungus, Agroathelia rolfsii. It’s often thought of as affecting hot Southern gardens, but has become more commonplace recently in the Northeast U.S. on tomatoes, pumpkins and squash, and other crops, including apples in Pennsylvania.

Other plant pathogens may take advantage of milder winter temperatures, which leads to prolonged saturation of soils instead of freezing. Both plants and microbes are less active when soil is frozen, but in wet soil, microbes have an opportunity to colonize dormant perennial plant roots, leading to more disease.

It can be challenging to accept that climate change is stressing some of your garden favorites, but there are thousands of varieties of plants to suit both your interests and your hardiness zone. Growing plants is an opportunity to admire their flexibility and the features that enable many of them to thrive in a world of change.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Matt Kasson, West Virginia University

Read more:

How to manage plant pests and diseases in your victory garden

Plants thrive in a complex world by communicating, sharing resources and transforming their environments

Climate change could enable Alaska to grow more of its own food – now is the time to plan for it

Matt Kasson receives funding from the US Department of Agriculture.

Comments