How ghost streams and redlining’s legacy lead to unfairness in flood risk, in Detroit and elsewhere

Published in Science & Technology News

In 2021, metro Detroit was hit with a rainstorm so severe that President Joe Biden issued a major disaster declaration at state officials’ request.

Nearly 8 inches of rain fell within 24 hours, closing every major freeway and causing massive damage to homes and businesses. The storm was of a severity historically seen in Detroit every 500 to 1,000 years.

But over the past decade, the region has experienced several other storms only slightly less destructive, one in August 2023.

As the planet warms, severe rains – and the flooding that follows – may become even more intense and frequent in cities like Detroit that have aging and undersized stormwater infrastructure. These extreme events put enormous pressure on communities, but low-income urban neighborhoods tend to suffer the most

I am a geomorphologist at the University of Michigan-Dearborn specializing in urban environments, water, historical mapping and flood-risk equity.

My recent research,conducted with graduate students Cat Sulich and Atreyi Guin, has identified a hidden contributor to flooding in older, low-income neighborhoods that have seen a lack of investment: ghost streams and wetlands.

Although we studied Detroit, our research has implications for cities across the United States.

Ghost streams and wetlands are waterways that previously existed but, as urban areas built up, were either buried below the surface or filled in to support development. Detroit has removed more than 85% of the total length of streams that existed in 1905. Most major cities in the United States and Europe have removed similar numbers of streams.

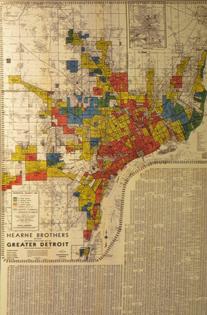

Detroit is also a city deeply affected by redlining – a now-outlawed practice once used by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a government-sponsored corporation that was created as part of the New Deal, that graded neighborhoods on perceived financial risk.

People living in communities labeled as “high risk” were disproportionately people of color, immigrants and residents of lower socioeconomic status and were systematically denied loans and opportunities to build generational wealth.

...continued

Comments