Even weak tropical cyclones have grown more intense worldwide – we tracked 30 years of them using currents

Published in Science & Technology News

Tropical cyclones have been growing stronger worldwide over the past 30 years, and not just the big ones that you hear about. Our new research finds that weak tropical cyclones have gotten at least 15% more intense in ocean basins where they occur around the world.

That means storms that might have caused minimal damage a few decades ago are growing more dangerous as the planet warms.

Warmer oceans provide more energy for storms to intensify, and theory and climate models point to powerful storms growing stronger, but intensity isn’t easy to document. We found a way to measure intensity by using the ocean currents beneath the storms – with the help of thousands of floating beachball-sized labs called drifters that beam back measurements from around the world.

Tropical cyclones are large storms with rotating winds and clouds that form over warm ocean water. They are known as tropical storms or hurricanes in the Atlantic and typhoons in the Northwest Pacific.

A tropical cyclone’s intensity is one of the most important factors for determining the damage the storm is likely to cause. However, it’s difficult to accurately estimate intensity from satellite observations alone.

Intensity is often based on maximum sustained surface wind speed at about 33 feet (10 meters) above the surface over a period of one, two or 10 minutes, depending on the meteorological agency doing the measuring. During a hurricane, that region of the storm is nearly impossible to reach.

For some storms, NOAA meteorologists will fly specialized aircraft into the cyclone and drop measuring devices to gather detailed intensity data as the devices fall. But there are many more storms that don’t get measured that way, particularly in more remote basins.

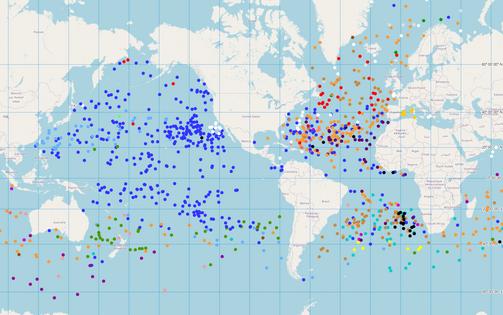

Our study, published in the journal Nature in November 2022, describes a new method to infer tropical cyclone intensity from ocean currents, which are already being measured by an army of drifters.

A drifter is a floating ball with sensors and batteries inside and an attached “drogue” that looks like a windsock trailing under the water beneath it to help stabilize it. The drifter moves with the currents and regularly transmits data to a satellite, including water temperature and location. The location data can be used to measure the speed of currents.

Since NOAA launched its Global Drifter Program in 1979, more than 25,000 drifters have been deployed in global oceans. Those devices have provided about 36 million records over time. Of those records, more than 85,000 are associated with weak tropical cyclones – those that are tropical storms or Category 1 hurricanes or typhoons – and about 5,800 that are associated with stronger tropical cyclones.

...continued

Comments