What is lake-effect snow? A climate scientist explains

Published in Science & Technology News

It’s hard for most people to imagine 4 feet of snow in one storm, like the Buffalo area was forecast to see this weekend, but these extreme snowfall events happen periodically along the eastern edges of the Great Lakes.

The phenomenon is called “lake-effect snow,” and the lakes themselves play a crucial role.

It starts with cold, dry air from Canada. As the bitter cold air sweeps across one or more of the relatively warmer Great Lakes, it sucks up more and more moisture that falls as snow.

I’m a climate scientist at UMass Amherst. In the Climate Dynamics course I teach, students often ask how cold, dry air can lead to heavy snowfall. Here’s how that happens.

Lake-effect snow is strongly influenced by the differences between the amount of heat and moisture at the lake surface and in the air a few thousand feet above it.

A big contrast creates conditions that help to suck water up from the lake, and thus more snowfall. A difference of 25 degrees Fahrenheit (14 C) or more creates an environment that can fuel heavy snows. This often happens in late fall, when lake water is still warm from summer and cold air starts sweeping down from Canada. More moderate lake-effect snows occur every fall under less extreme thermal contrasts.

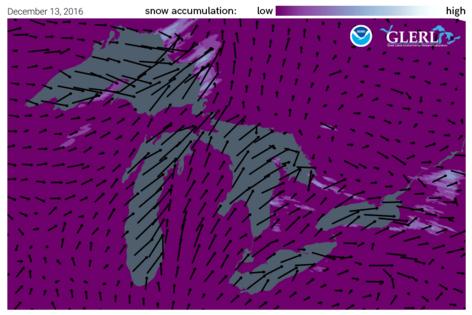

Wind direction is important too. The farther cold air travels over the lake surface, the more moisture is evaporated from the lake. A long “fetch” – the distance over water – often results in more lake-effect snow than a shorter one.

Imagine a wind out of the west that is perfectly aligned so that it blows over the entire 241-mile length of Lake Erie. That’s close to what Buffalo was experiencing the weekend of Nov. 18, 2022.

Once the snow reaches land, elevation contributes an additional effect. Land that slopes up from the lake increases lift in the atmosphere, enhancing snowfall rates. This mechanism is termed “orographic effect.” The Tug Hill plateau, located between the lake and the Adirondacks in western New York, is well known for its impressive snowfall totals.

In a typical year, annual snowfall in the “lee,” or downwind, of the Great Lakes approaches 200 inches in some places.

Residents in places like Buffalo are keenly aware of the phenomenon. In 2014, some parts of the region received upwards of 6 feet of snowfall during an epic lake-effect event Nov. 17-19. The weight of the snow collapsed hundreds of roofs and led to over a dozen deaths.

Lake-effect snowfall in the Buffalo area is typically confined to a narrow region where the wind is coming straight off the lake. Drivers on Interstate 90 often go from sunny skies to a blizzard and back to sunny skies over a distance of 30 to 40 miles.

Is climate change playing a role in the lake-effect snow machine? To an extent.

Fall has warmed across the upper Midwest. Ice prevents lake water from evaporating into the overlying air, and it is forming later than in the past. Warmer summer air has led to warmer lake temperature into fall.

Models predict that with additional warming, more lake-effect snow will occur. But over time, the warming will lead to more of the precipitation falling as lake-effect rain, which already occurs in early fall, rather than snow.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Michael A. Rawlins, UMass Amherst. Like this article? subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more:

How is snowfall measured? A meteorologist explains how volunteers tally up winter storms

The water cycle is intensifying as the climate warms, IPCC report warns – that means more intense storms and flooding

Michael A. Rawlins receives funding from the Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the National Science Foundation.

Comments