Current News

/ArcaMax

Immigration agents arrest 87 with commercial driver's licenses in California

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Border Patrol agents arrested 42 people with commercial driver’s licenses issued to immigrants, including 31 from California, who were taken into custody at immigration checkpoints and highways.

Another federal immigration operation targeting California trucking companies over two days last week led to the arrests of 45...Read more

Brightline sued for $60 million by ex-conductor diagnosed with PTSD after witnessing 7 deaths

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — A former Brightline conductor filed a federal lawsuit against the company this week, asserting that the job caused him severe PTSD after repeatedly witnessing brutal crashes and violent deaths throughout his five years operating the high-speed passenger trains.

Darren J. Brown Jr. worked as a Brightline conductor ...Read more

Modi fast-tracks reforms to shield economy from US tariffs

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government pushed through far-reaching policy reforms in the final parliamentary session of the year, seeking to bolster the economy in the face of trade headwinds.

In one of its most active winter sittings in recent years, the Parliament approved bills to open the nuclear industry to private companies and allow...Read more

Idaho attorney general challenges Trump stance on marijuana risk

BOISE, Idaho — Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador on Friday raised “concerns” about President Donald Trump’s Thursday executive order calling for the downgrade of marijuana from a Schedule I to a Schedule III drug. The administration called for the change to increase access to marijuana for medical uses, the order said.

“The ...Read more

Walz says there's no evidence of $9 billion in fraud, exposing rift between state and feds

MINNEAPOLIS — Gov. Tim Walz lashed out at federal prosecutors Friday for proclaiming without evidence that the total amount of fraud in Minnesota social services programs could top $9 billion.

“It’s speculating,” Walz told reporters during a news conference at the State Capitol. “To extrapolate what that number is for sensationalism, ...Read more

Justice Department appeals dismissal of James, Comey indictments

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Justice Department is appealing the dismissal of indictments against New York Attorney General Letitia James and former FBI Director James Comey, after a judge concluded the prosecutor who brought the cases had been appointed to the post illegally when she was handpicked by President Donald Trump.

In separate court ...Read more

US launches retaliatory strikes in Syria after Trump threat

WASHINGTON — The U.S. launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said Friday, fulfilling President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two U,S soldiers.

“This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said in a post on X....Read more

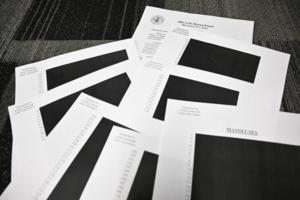

DOJ releases first round of the Epstein Files. Here's what we know so far

After nearly two decades, the Justice Department on Friday finally released at least a portion of its files on the late sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein — but a very small one.

The documents are part of the voluminous government files gathered by the DOJ through four presidential administrations, which officials have said number in the hundreds...Read more

US launches retaliatory strikes in Syria after Trump threat

WASHINGTON — The U.S. launched large-scale airstrikes on Syria, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said Friday, fulfilling President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two U.S. soldiers.

“This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” Hegseth said in a post on X. “Today, we hunted and we ...Read more

Wyoming Sen. Cynthia Lummis will not run for reelection in 2026

WASHINGTON — Wyoming Sen. Cynthia Lummis is retiring from the Senate after a single term, leaving behind an open seat in a reliably red state.

She’s the fifth Republican senator to decide against running for reelection to the chamber in 2026.

Lummis, 71, a strong ally of the crypto industry, said the decision represented “a change of ...Read more

News briefs

A Reddit post from a homeless man at Brown University helped investigators find mass shooter

BOSTON — Police are probably going to sift through a lot more Reddit posts in the future. One of those online posts played a big role in helping investigators find the suspect who killed two students at Brown University, and injured nine others, ...Read more

9 drugmakers strike deals with Trump, with more to come

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump announced deals with nine pharmaceutical companies on Friday, the latest in a series of pacts designed to lower drug prices for some Americans in exchange for a three-year reprieve from threatened tariffs.

The most recent pledges mean 14 of the 17 drugmakers targeted by Trump this summer have agreed to ...Read more

Justice Department releases Epstein investigative documents

WASHINGTON — The Justice Department released a trove of investigative documents on dead sex offender Jeffrey Epstein Friday, with the department’s second-in-command indicating the records would only represent a partial disclosure of those available.

The comments from Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche quickly drew outrage from ...Read more

Justice Department releases Epstein files, with redactions and omissions

WASHINGTON — The Justice Department released a library of files on Friday related to Jeffrey Epstein, partially complying with a new federal law compelling their release, while acknowledging that hundreds of thousands of files remain unsealed.

The portal, on the department’s website, includes videos, photos and documents from the years-...Read more

Research shows proton beam therapy improves cancer survival, lowers side effects

Proton beam radiation therapy performed 10% better at stopping cancer of the throat compared to traditional X-ray radiation, a new study shows, with 15% fewer side effects.

“With this study, it is my personal belief that proton beam therapy is a new standard-of-care treatment for patients with oropharyngeal cancer,” said Dr. Jason Molitoris...Read more

California sees population growth for third consecutive year after pandemic-era exodus

LOS ANGELES — For the third consecutive year, California’s population has increased, though the Golden State has still not reached its pre-pandemic population high.

The state’s population grew by about 19,200 people, marking a 0.05% increase from July 1, 2024, to July 1, 2025, according to data released Friday by the California Department...Read more

Trump aides hold another round of Ukraine peace talks in Miami

MIAMI — International leaders are descending on Miami this weekend for rounds of negotiations with President Donald Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff and son-in-law Jared Kushner, including the head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund Kirill Dmitriev on Saturday.

On Friday morning, Witkoff and Kushner met with Ukraine’s national ...Read more

Judge overturns Run-DMC's Jam Master Jay murder suspect's conviction

NEW YORK — A federal judge has overturned the conviction of Karl Jordan, one of the two men accused of killing Run-DMC legend Jam Master Jay, the Daily News has learned.

In a decision filed in federal court Friday, U.S. District Judge LaShann DeArcy Hall granted the acquittal asked for by Jordan’s attorneys. A new trial was not ordered.

A ...Read more

DOJ releases first round of the Epstein files. Here's what we know so far

After nearly two decades the Justice Department on Friday finally released at least a portion of its files on the late sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein.

The documents are part of the voluminous government files gathered by the DOJ through four presidential administrations. They were published in four parts on the DOJ website, and are expected to ...Read more

Justice Department releases Epstein investigative documents

WASHINGTON — The Justice Department released a trove of investigative documents on dead sex offender Jeffrey Epstein on Friday, with the department’s second-in-command indicating the records would only represent a partial disclosure of those available.

The comments from Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche quickly drew outrage from ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Nick Reiner's schizophrenia meds made him 'erratic,' sources say

- Commentary: Donald Trump wants a resurgence in European nationalism

- She was approved for a green card after 3 decades in the US. Then ICE arrested her

- Who's running the LAPD? Chief's style draws mixed reviews in first year

- Brown University shooter found dead in New Hampshire: reports