Trump charged under Espionage Act – which covers a lot more crimes than just spying

Published in News & Features

Former President Donald Trump’s indictment by a federal grand jury in Miami includes at least one charge under the Espionage Act of 1917, according to Trump’s attorney and reports in The New York Times.

The Espionage Act has historically been employed most often by law-and-order conservatives. But the biggest uptick in its use occurred during the Obama administration, which used it as the hammer of choice for national security leakers and whistleblowers. Regardless of whom it is used to prosecute, it unfailingly prompts consternation and outrage.

We are both attorneys who specialize in and teach national security law. While navigating the sound and fury over the Trump indictment, here are a few things to note about the Espionage Act.

When you hear “espionage,” you may think spies and international intrigue. One portion of the act – 18 U.S.C. section 794 – does relate to spying for foreign governments, for which the maximum sentence is life imprisonment.

That aspect of the law is best exemplified by the convictions of Jonathan Pollard in 1987, for spying for and providing top-secret classified information to Israel; former Central Intelligence Agency officer Aldrich Ames in 1994, for being a double agent for the Russian KGB; and, in 2002, former FBI agent Robert Hanssen, who was caught selling U.S. secrets to the Soviet Union and Russia over a span of more than 20 years. All three received life sentences.

But spy cases are rare. More typically, as in the Trump investigation, the act applies to the unauthorized gathering, possessing or transmitting of certain sensitive government information.

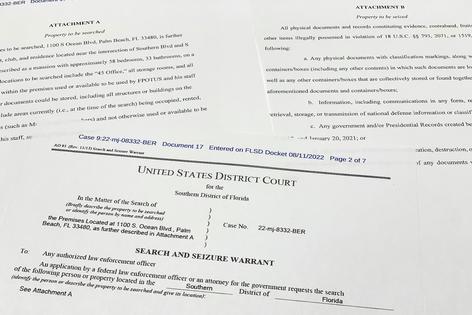

Transmitting can mean moving materials from an authorized to an unauthorized location – many types of sensitive government information must be maintained in secure facilities. It can also apply to refusing a government demand for a document’s return. Trump’s charges reportedly include an allegation of “unauthorized retention of national security documents,” which can include both possessing the documents and refusing to return them to the government. All of these prohibited activities fall under the separate and more commonly applied section of the act – 18 U.S.C. section 793.

Willful unauthorized possession of information that, if obtained by a foreign government, might harm U.S. interests is generally enough to trigger a possible sentence of 10 years.

Current claims by Trump supporters of the seemingly innocuous nature of the conduct at issue – simply possessing sensitive government documents – miss the point. The driver of the Department of Justice’s concern under Section 793 is the sensitive content and the connection to national defense information, known as “NDI.”

One of the most famous Espionage Act cases, known as “Wikileaks,” in which Julian Assange was indicted for obtaining and publishing secret military and diplomatic documents in 2010, is not about leaks to help foreign governments. It concerned the unauthorized soliciting, obtaining, possessing and publishing of sensitive information that might be of help to a foreign nation if disclosed.

Two recent senior Democratic administration officials – Sandy Berger, national security adviser during the Clinton administration, and David Petraeus, CIA director under during the Obama administration – each pleaded guilty to misdemeanors under the threat of Espionage Act prosecution.

Berger took home a classified document – in his sock – at the end of his tenure. Petraeus shared classified information with an unauthorized person for reasons having nothing to do with a foreign government.

Some of the documents the FBI sought and found in the Trump search were designated “top secret” or “top secret-sensitive compartmented information.”

Both classifications tip far to the serious end of the sensitivity spectrum.

Top secret-sensitive compartmented information is reserved for information that would truly be damaging to the U.S. if it fell into foreign hands.

One theory floated by Trump defenders is that by simply handling the materials as president, Trump could have effectively declassified them. It actually doesn’t work that way – presidential declassification requires an override of Executive Order 13526, must be in writing, and must have occurred while Trump was still president – not after. If they had been declassified, they should have been marked as such.

And even assuming the documents were declassified, which does not appear to be the case, Trump is still in the criminal soup. The Espionage Act applies to all national defense information, or NDI, of which classified materials are only a portion. This kind of information includes a vast array of sensitive information including military, energy, scientific, technological, infrastructure and national disaster risks. By law and regulation, NDI materials may not be publicly released and must be handled as sensitive.

Cases involving classified information or NDI are nearly impossible to referee from the cheap seats.

None of us will get to see the documents at issue, nor should we. Why?

Because they are classified.

Even if we did, we would not be able to make an informed judgment of their significance because what they relate to is likely itself classified – we’d be making judgments in a void.

And even if a judge in an Espionage Act case had access to all the information needed to evaluate the nature and risks of the materials, it wouldn’t matter. The fact that documents are classified or otherwise regulated as sensitive defense information is all that matters.

Historically, Espionage Act cases have been occasionally political and almost always politicized. Enacted at the beginning of U.S. involvement in World War I in 1917, the act was largely designed to make interference with the draft illegal and prevent Americans from supporting the enemy.

But it was immediately used to target immigrants, labor organizers and left-leaning radicals. It was a tool of Cold War anti-communist politicians like Sen. Joe McCarthy in the 1940s and 1950s. The case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, executed for passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, is the most prominent prosecution of that era.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the act was used against peace activists, including Pentagon Paper whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Since Sept. 11, 2001, officials have used the act against whistleblowers like Edward Snowden. Because of this history, the act is often assailed for chilling First Amendment political speech and activities.

The Espionage Act is serious and politically loaded business. Its breadth, the potential grave national security risks involved and the lengthy potential prison term have long sparked political conflict. These cases are controversial and complicated in ways that counsel patience and caution before reaching conclusions.

This is an updated version of an article originally published Aug. 15, 2022.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more:

Do federal or state prosecutors get to go first in trying Trump? A law professor untangles the conflict

Trump faces possible obstruction of justice charges for concealing classified government documents – 2 important things to know about what this means

Thomas A. Durkin was an expert witness on behalf of Julian Assange in his UK proceeding.

Joseph Ferguson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments