Current News

/ArcaMax

Police walk a tightrope to maintain community relations amid Twin Cities ICE arrests

Hours after news of an impending federal immigration crackdown sent shock waves through the Somali community, Chief Brian O’Hara stood in solidarity with vulnerable residents.

At a news conference, he reiterated that his officers do not cooperate with immigration enforcement and that his agency is not notified in advance about ICE raids. He ...Read more

Disability rights lawyers threatened with budget cuts, reassignments

The Trump administration is trying to slash access to lawyers who defend the rights of Americans with disabilities, advocates say.

Most of the lawyers work either for the Department of Justice or for disability rights agencies that Congress set up in every state decades ago. Many of the Justice Department lawyers quit in 2025 after being ...Read more

The Minnesota mom who ignited RFK's vaccine concerns and today's MAHA movement

MINNEAPOLIS — The coastal sun was shining on Sarah Bridges, she recalled, when she decided to stage a one-person protest on Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s porch in Hyannis Port.

The Minnesota mom would sit there — after showing up unannounced in 2005 with an 18-inch stack of documents — until the famed environmental attorney agreed to read the...Read more

Trump's tirade puts San Diego Somali community on edge. 'We are not garbage. We are neighbors.'

It was the words of President Donald Trump, spoken 2,300 miles away, that prompted Mikaiil Hussein — a U.S. citizen who first came as a refugee from Somalia over 30 years ago — to take steps to protect himself.

The labor leader said that he now carries his U.S. passport card with him wherever he goes, in case he is stopped by federal ...Read more

Halfway through Florida's bear hunt, state officials won't say how many bears are dead

Florida’s first statewide black bear hunt in a decade is more than halfway over but state wildlife leaders have offered no information on its progress, not even a death count.

“Are we overkilling like in 2015?” asked Joe Humphrey, a Seminole County resident who described himself as a hunter at odds with the Fish & Wildlife Conservation ...Read more

US pursuit of third oil tanker intensifies Venezuela blockade

The U.S. has pursued a third oil tanker off the coast of Venezuela, intensifying a blockade that the Trump administration hopes will cut off a vital economic lifeline for the country and isolate the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

The U.S. Coast Guard chased the U.S.-sanctioned Bella 1 on Sunday as it was en route to Venezuela. It ...Read more

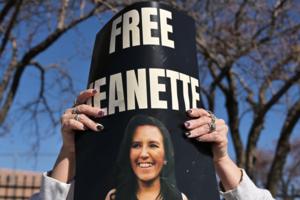

Jeanette Vizguerra, detained immigrant activist, likely to be released in coming days

Immigrant activist Jeanette Vizguerra is on the precipice of being released from an immigration detention facility after an immigration judge ruled Sunday that she can post bail.

Denver immigration judge Brea Burgie set Vizguerra’s bail at $5,000, but she included no other restrictions, like an ankle monitor. Her family intends to immediately...Read more

Trump taps Louisiana Governor Landry as Greenland envoy

President Donald Trump said he’s nominating Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry as U.S. special envoy to Greenland, in the latest signal that the president retains designs on increasing U.S. influence over the island he’s suggested he wants to purchase.

“Jeff understands how essential Greenland is to our National Security, and will strongly ...Read more

Support for Japan's Takaichi stays firm as China dispute festers

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s support ratings held steady at historically high levels according to polls conducted over the weekend, in a sign of her continued popularity despite the fallout from a dispute with China over comments she made on Taiwan last month.

Surveys conducted over the weekend showed that about 70% of respondents...Read more

New Zealand reported to have finalized trade deal with India

New Zealand has finalized a free-trade agreement with India, local media including BusinessDesk and Radio NZ reported, citing unidentified officials.

The accord follows Trade Minister Todd McClay’s recent trip to India, according to the reports. McClay and Prime Minister Christopher Luxon are due to hold a news conference later Monday in ...Read more

In the Caribbean, a dispute over sovereignty and Washington's influence

Former Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister Keith Rowley is accusing his nation’s current leader of “betraying” regional sovereignty on behalf of the United States, warning that she risks reducing the oil-rich twin-island nation to “a vassal state.”

Rowley, who stepped down as leader of both his country and the People’s National ...Read more

Earthquake swarm continues to rattle Northern California city, seismologists say

A swarm of at least a dozen earthquakes reaching up to magnitude 3.9 rattled San Ramon near San Francisco, the U.S. Geological Survey reports.

The other quakes in the Saturday, Dec. 21, swarm ranged from magnitude 1.3 to 3.0, according to the USGS.

San Ramon earlier was hit by a swarm of more than 90 quakes starting Nov. 9, The Sacramento Bee ...Read more

Lawsuit released in Epstein files claims connection to Michigan summer camp

The federal government's release of thousands of files related to Jeffrey Epstein included a lawsuit that claimed he met his first known victim at a Michigan fine arts summer camp in the 1990s.

The complaint, filed in May 2020 by Los Angeles-based Panish Shea & Boyle LLP on behalf of a Jane Doe, said Jane Doe met when she was 13 the late-...Read more

Starmer and Trump discuss Ukraine, Gaza and new UK ambassador

U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer and U.S. President Donald Trump discussed Ukraine and Gaza during a pre-Christmas phone call on Sunday, according to a statement released by Downing Street in London.

Starmer also updated Trump on the choice of a new British ambassador to Washington after Peter Mandelson was fired in September over his ...Read more

Trump denies disaster declarations for Colorado fires, flooding: 'We won't stop fighting'

President Donald Trump denied two disaster declaration requests from Colorado that would have allowed the state to receive federal assistance — a move state lawmakers announced Sunday that they plan to appeal.

“Coloradans are trying to rebuild their lives after fires and floods destroyed homes and communities across our state,” Sen. John ...Read more

NYPD cop loses month pay for kneeling on back of Manhattan suspect who yelled 'I can't breathe'

An NYPD cop lost 30 days pay for kneeling on the back of an emotionally disturbed Manhattan suspect as he cried out “I can’t breathe,” the Daily News has learned.

Officer Gabriel Perez-Ponce was penalized by NYPD Commissioner Jessica Tisch in September after she agreed with the findings of an NYPD judge who earlier this year presided over...Read more

Deputy AG Blanche says pulling Trump photo from Epstein file was right

Justice Department officials were protecting victims of Jeffrey Epstein when they removed several images from agency’s release of files tied to the notorious sex offender, Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche said.

“There were a number of photographs that were pulled down after being released on Friday,” Blanche said on NBC’s "Meet the ...Read more

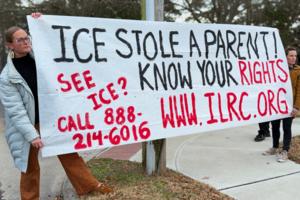

ICE moves Maryland mother out of state, as attorneys try to get hearing set

A Salisbury, Md., mother detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) last week has been transferred to a Louisiana facility, a move her attorneys say has delayed court proceedings that could determine whether she is eligible for release on bond.

Vanessa Parrazal, 24, was taken into ICE custody Dec. 17 just minutes after dropping ...Read more

Nick Reiner was prescribed schizophrenia medication before killings of Rob, Michele Reiner, sources say

Nick Reiner had been prescribed medication for schizophrenia at some point before he allegedly killed his parents, Hollywood legend Rob Reiner and photographer Michele Reiner, according to two sources with knowledge of the investigation.

It is unclear the name of the drug and how long he had been prescribed it. No other details were available. ...Read more

More than 20,000 still without power after massive San Francisco blackout

Roughly 110,000 PG&E customers have service again following a major power outage Saturday in San Francisco that left homes in the dark, stalled traffic and shut down restaurants, shops and holiday lighting displays.

PG&E said on social media that the remaining 21,000 without power are concentrated in Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, the Richmond...Read more

Popular Stories

- Column: Political giants and moral degenerates: My five best books of 2025

- Florida set a record for executions in 2025. What to know

- Flu season could get a lot worse in the coming weeks, experts say

- New Maryland laws coming into effect New Year's Day 2026

- One big beautiful bill act complicates state health care affordability efforts