Business

/ArcaMax

Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz leaves Seattle for Miami

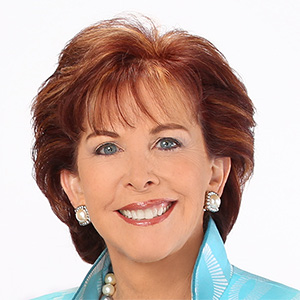

Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, whose vision shaped the coffee giant’s growth into a global brand, has departed his longtime home of Seattle for sunny Miami.

Schultz, who served as CEO three separate times at the Seattle-based company, announced the tandem decision with his wife, Sheri, on LinkedIn on Tuesday evening.

“For those of ...Read more

Panera debuts new energy refresher drinks, less caffeine than its 'charged lemonade'

Nearly two years after Panera Bread got rid of its “charged lemonade,” the cafe chain is introducing two new caffeinated energy refresher drinks.

In 2023, a pair of wrongful-death lawsuits were filed against Panera in relation to its caffeinated lemonade. Sarah Katz’s family claimed that Katz, a 21-year-old University of Pennsylvania ...Read more

Aetna agreed to pay $117.7 million in Medicare Advantage false claims settlement

Aetna, the second-biggest Medicare Advantage company in the Philadelphia area, has agreed to pay $117.7 million to settle claims of false billing, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia announced Wednesday.

Government investigators found that Aetna added diagnosis codes to patient records to generate larger monthly payments for people in ...Read more

Protesters target Citizens Bank for funding US ICE detention contractors CoreCivic, Geo Group

PHILADELPHIA — Citizens Bank, based in Providence, Rhode Island, has built one of the largest U.S. commercial-banking networks by courting middle-sized U.S. companies, leaving the biggest corporations and their foreign-trade complications to the larger New York banks.

But Citizens also has found success financing two profitable, U.S.-focused ...Read more

Iran-linked group claims responsibility for Stryker cyberattack

An Iranian-linked group claimed responsibility Wednesday for a cyberattack against Michigan-based medical giant Stryker Corp., an incident that cybersecurity experts said could be one of unprecedented in size and scope.

A global outage afflicted the company in the early hours of Wednesday, with employees and contractors saying that the logo of ...Read more

US budget deficit narrows at slower pace after tariff rate decrease

The budget deficit narrowed in February at a slower pace than the previous month as U.S. tariff revenue started to slow from the peak rate hit late last year.

For the five months through February, the government had a deficit of $1 trillion, down $148 billion from the same period the year before, after accounting for calendar-year differences, ...Read more

Yamaha is leaving California after nearly 50 years

Yamaha Motor Corp. is relocating part of its operations to Georgia and selling its California assets after 47 years.

The company is the latest among a slew of businesses to relocate operations outside the Golden State to cut costs and improve profitability. Many cite high taxes and strict regulations as obstacles to doing business in the state....Read more

Moody's downgrades NYC financial outlook to 'negative' citing budget deficit

Moody’s Ratings has projected a negative outlook for New York City’s finances, chalking it up to the city’s large and persistent projected budget gaps — and citing Mayor Mamdani’s plan to draw down from reserves in order to balance the budget this year.

The negative outlook won’t have any immediate impact on the city’s borrowing ...Read more

NHTSA takes 'milestone' step toward robotaxi commercial deployment

WASHINGTON — The federal government has begun the process of exempting the nation’s first purpose-built robotaxi from certain safety standards so it can deploy commercially on American roads.

Amazon.com Inc. subsidiary Zoox petitioned the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in August for such exemptions so it could place up to 2,...Read more

California's heralded wine industry is running dry -- here's why

Winery owner Stuart Spencer estimates that he left about 50 tons of grapes to rot on vines in Lodi, California, last fall, as harvesting and processing them would have cost more than they were worth.

“We’re doing our best to keep our head above water,” said Spencer, the owner of St. Amant Winery and executive director of the Lodi ...Read more

Spotify once had a reputation for underpaying music artists. It hopes to change that perception

Back in the early 2010s, the music industry was at a low point.

Piracy was rampant. Compact disc sales were on a steady decline. And the then-new audio streaming services, like Spotify, were taking hits from creators for paying low royalty rates.

Today, Spotify has grown into the world's most popular audio streaming subscription service and ...Read more

Ford Pro telematics customers now have access to an AI-powered chatbot

Ford Motor Co.'s commercial fleet customers now have access to a new artificial intelligence-powered chatbot within the Ford Pro Telematics Software platform that can help provide information faster, flag maintenance needs sooner and suggest tips for greater efficiency.

AI has become the fastest-adopted technology with chatbots increasingly ...Read more

Robotaxis could see 'public backlash' amid job loss fears, San Diego study says

As San Diego awaits the state’s review of its anti-Waymo protest, a new study reveals widespread fear that robotaxis could cost jobs, exacerbate income inequality, and cause broader economic disruption.

“If we don’t address these fears in a forward-looking manner, we may end up in a situation where we see a public backlash against this ...Read more

Boeing gets $298 million Israel deal for 5,000 smart bombs

Boeing Co. has a new $298 million contract with Israel to deliver as many as 5,000 new air-launched smart bombs, according to three people familiar with the transaction.

The company’s Small Diameter Bomb is a guided munition that can be launched by Israeli jets at targets more than 40 miles (64 kilometers) away.

The new contract is not ...Read more

Anthropic tells judge it could lose billions If US shuns AI tool

Anthropic PBC told a judge it could lose as much as billions of dollars in revenue this year and urged quick action on its request to block the Trump administration’s declaration of the company as a supply-chain risk after a blowup with the Pentagon over artificial intelligence safety issues.

A lawyer for the startup made a case for urgency ...Read more

Disneyland Resort President Thomas Mazloum named parks chief

Disneyland Resort President Thomas Mazloum has been named chairman of Walt Disney Co.'s experiences division, the company said Tuesday.

Mazloum succeeds soon-to-be Disney Chief Executive Josh D'Amaro as the head of the Mouse House's vital parks portfolio, which has become the economic engine for the Burbank media and entertainment giant. His ...Read more

LAX board approves fee hike for companies like Uber, Lyft and others

Your next trip to or from LAX might soon get more expensive if you're grabbing a taxi or turning to a phone app for a ride.

On Tuesday, board members for the Los Angeles World Airports approved a fee hike for private transportation companies that pick up and drop off passengers at Los Angeles International Airport. The access fee increase ...Read more

Target's 'shrink' back to pre-pandemic levels, but it's not all about theft

Retailers across the country, including Target, say one metric is finally improving: Shrink is returning to pre-pandemic levels.

That’s good news for the Minneapolis-based retailer’s bottom line. At one point amid the supply chain crisis following the pandemic, executives said they expected shrink, mainly from theft and organized retail ...Read more

Boeing is reworking some 737 Max planes to fix scratches on wires

Boeing is reworking some 737 Max planes to fix small scratches on wires, the company said Tuesday.

The scratches were caused by a machining error and do not present an immediate safety issue, according to Boeing's engineering analysis.

Boeing is repairing planes that have already moved through its production line but have not yet been ...Read more

Opening arguments begin in first Illinois trial against Abbott over its formula for premature babies

CHICAGO — Four Illinois mothers would never have allowed their prematurely born babies to be fed a specialized formula made by Abbott Laboratories had they known about the risks, an attorney for the parents argued in court Monday, while a lawyer for the company countered that the formula is not dangerous and that additional warnings about it ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Anthropic tells judge it could lose billions If US shuns AI tool

- Boeing gets $298 million Israel deal for 5,000 smart bombs

- California's heralded wine industry is running dry -- here's why

- As gas prices rise, California gets punched harder at the pump than other states

- NHTSA takes 'milestone' step toward robotaxi commercial deployment