Sports

/ArcaMax

Angels restructure Anthony Rendon's deal, ending his time in uniform

Anthony Rendon’s time in an Angels uniform is over.

The Angels and Rendon have agreed to restructure his contract just before the final season of the seven-year, $245 million deal, a source confirmed on Tuesday.

It is unclear exactly how the money will be reallocated. Rendon was owed $38 million in the final year of the deal. Per the terms ...Read more

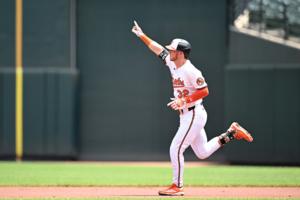

Analysis: Even after Eflin deal, Orioles have room for a frontline starter

BALTIMORE — The Orioles’ one-year deal with Zach Eflin on Sunday ensured they will go into next season with a rotation of five quality starting pitchers and some capable depth behind them. As last year taught them, a team with World Series aspirations needs more than that.

Eflin, who re-signed for $10 million and a 2027 mutual option, is ...Read more

The 10 games that defined the 2025 Minnesota Twins season

What is the best way to describe the 2025 Twins season in one word:

Embarrassing? Disappointing? Chaotic?

It was at least eventful. The Twins were rarely boring. They started out poorly, ripped off a 13-game winning streak in May, watched their pitching fall apart in June and traded more than a third of the roster in July.

As we reach the ...Read more

Abbey Mastracco: The case for David Wright in the Hall of Fame

NEW YORK — David Wright looks as though he’ll receive enough votes to remain on the National Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for another year, allowing voters another year to examine his candidacy. The former Mets third baseman has received more votes in each of the last three years, but he’s still nowhere near the 75% threshold needed to be ...Read more

Analysis: Mariners' Rob Refsnyder signing makes them a better team

SEATTLE — When the Mariners announced the signing of veteran hitter Rob Refsnyder to a one-year, $6.5 million contract, there was some consternation among the fan base (like always) about his fit or need on the Mariners' 26-man roster.

Of course, many fans were awaiting some movement on potential trades for Cardinals infielder Brendan Donovan...Read more

Tom Krasovic: Newest Padre could prove beneficial for Manny Machado, continue Pacific Rim pipeline

SAN DIEGO — I like the basic thinking behind utility Sung-Mun Song, 29, joining the Padres this week.

Song’s best position is third base. He bats left-handed, a nice touch.

Out of respect for the daunting jump from the top Korean league to Major League Baseball, where fastball speeds tend to be 2-3 mph higher, any projection for Song must ...Read more

David Murphy: Matt Strahm, Phillies seventh innings, and Dave Dombrowski's high-risk trade

PHILADELPHIA — There were some signs that the Phillies and Matt Strahm weren’t long for this world. Small ones. The kind you see in a lot of relationships between headstrong people. Certainly nothing that suggested things were fractured beyond repair. Still, there was enough smoke to at least dampen the surprise when the Phillies decided to ...Read more

As Rays build a young nucleus, they also value some key veteran advice

TAMPA, Fla. — In trading four big leaguers for six prospects plus a draft pick last week, the Rays continued their purge of players who finished last season on their roster or 60-day injured list, with 24 of 49 now gone.

That extreme makeover is part of a plan to rebuild with a core of young players who can, in theory, form a nucleus capable ...Read more

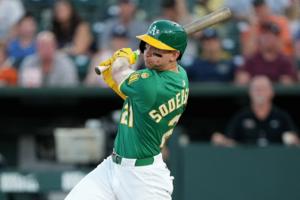

A's, outfielder Tyler Soderstrom agree to franchise-record contract extension: Report

LAS VEGAS — The Athletics have agreed with left fielder Tyler Soderstrom on a seven-year, $86 million contract extension, ESPN reported Thursday.

The deal is reportedly the largest guaranteed contract in franchise history.

Soderstrom hit 25 homers with a .275 batting average and 93 RBIs last season for the A’s, who are scheduled to move to...Read more

Joe Starkey: Better late than never, Pirates. This is going to be interesting.

PITTSBURGH — In some ways, I would imagine, the Pirates finally making significant moves might only serve to fuel one's rage over last offseason and the many before it.

Especially last offseason, and how they wasted another precious year of Paul Skenes.

But that is water under the Clemente Bridge now. The Pirates are finally putting action ...Read more

Marlins add veteran closer Pete Fairbanks in biggest free-agent pickup in years

MIAMI — The Marlins made their first sizable free-agent investment in two years on Wednesday, agreeing to terms with veteran right-hander closer Pete Fairbanks on a one-year, $13 million deal.

The deal is agreed to but contingent on Fairbanks passing a physical, according to a source.

Fairbanks will become the team’s second-highest paid ...Read more

John Romano: Oh no, the Rays traded Brandon Lowe! (Now pass me another beer).

TAMPA, Fla. — The complaints are valid and, the way things work around here, pretty much eternal.

Yes, the Rays have gotten rid of another fan favorite. On the list of franchise records, Brandon Lowe is eighth in games played, third in home runs, fourth in slugging percentage and sixth in OPS. Odds are, the Rays will get less production out ...Read more

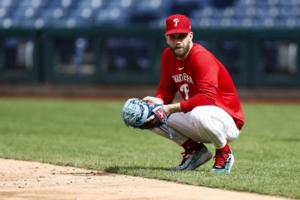

Bryce Harper plans to play for Team USA in the World Baseball Classic

PHILADELPHIA — Bryce Harper’s dream is to compete in the Olympics.

First, he’ll suit up for the World Baseball Classic.

Harper announced his plans Tuesday on Instagram, posting a photo of himself superimposed in a Team USA jersey. The Phillies star joins a loaded roster that includes Aaron Judge, Cal Raleigh, Bobby Witt Jr., teammate ...Read more

Sources: Pirates sign free agent OF/1B Ryan O'Hearn to 2-year, $29 million contract

PITTSBURGH — Three days after acquiring Brandon Lowe from the Tampa Bay Rays, the Pirates have doubled down on their pre-Christmas spending, signing free agent outfielder/first baseman Ryan O’Hearn to a two-year, $29 million contract with incentives, sources told the Post-Gazette.

O’Hearn, 32, batted .281 with 17 homers, 63 RBIs and an ....Read more

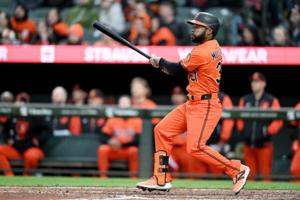

Paul Sullivan: Munetaka Murakami is the low-risk gamble the White Sox had to make in Year 4 of the rebuild

CHICAGO — Now would be a good time for all Chicago White Sox fans to declare their true feelings about the state of the organization as the team ends 2025 on an upbeat note.

Is the hard part of the rebuild finally over, or is “Mune Time” a mirage?

The signing of Japanese slugger Munetaka Murakami, whom Sox general manager Chris Getz ...Read more

Mets trade Jeff McNeil, cash for minor league pitcher: source

NEW YORK — David Stearns has effectively taken a wrecking ball to the New York Mets core.

The team traded former NL batting champ Jeff McNeil to the Athletics on Monday, a source confirmed to the New York Daily News. It appears to be a bigger move for the A’s than the Mets. According to ESPN’s Jeff Passan, the Mets are receiving only 17-...Read more

Paul Sullivan: Cubs' Matt Shaw enters a new world with his Turning Point USA appearance

CHICAGO — Matt Shaw was back in a familiar place this weekend.

But instead of speaking to a dozen or so media members in front of his Wrigley Field locker, the Chicago Cubs third baseman was wearing a sports coat and addressing hundreds of people at an annual Turning Point USA event in Phoenix.

Shaw’s media gathering in late September was ...Read more

Jason Mackey: Is it OK to say Ben Cherington has had a solid offseason (so far) for the Pirates?

MONTREAL — Ben Cherington has been an easy and understandable target for criticism due to the Pittsburgh Pirates topping out at 76 wins since he took over in 2019.

There have been trades that haven't worked out, too few position player prospects developed and a checkered history in free agency.

But there's really no other way to slice this ...Read more

Report: Red Sox acquire 1B Willson Contreras from Cardinals

BOSTON — The Boston Red Sox have finally landed their first bat of the offseason.

According to multiple reports, the Red Sox have acquired first baseman Willson Contreras from the St. Louis Cardinals in exchange for right-hander Hunter Dobbins and pitching prospects Yhoiker Fajardo and Blake Aita.

ESPN’s Jeff Passan was first to report ...Read more

White Sox sign Japanese slugger Munetaka Murakami to 2-year, $34 million deal

CHICAGO — The Chicago White Sox have been looking for more power. They might have found an answer after landing Japanese free-agent slugger Munetaka Murakami.

The Sox are signing the left-handed hitting infielder to a two-year, $34 million contract, a source confirmed to the Chicago Tribune. The club made the signing official later Sunday ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Angels restructure Anthony Rendon's deal, ending his time in uniform

- Analysis: Even after Eflin deal, Orioles have room for a frontline starter

- Abbey Mastracco: The case for David Wright in the Hall of Fame

- The 10 games that defined the 2025 Minnesota Twins season

- Analysis: Mariners' Rob Refsnyder signing makes them a better team