Politicians may rail against the ‘deep state,’ but research shows federal workers are effective and committed, not subversive

Published in Political News

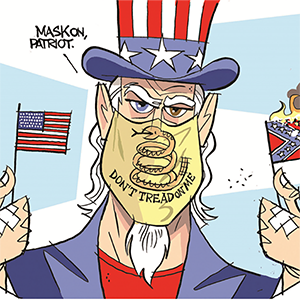

It’s common for political candidates to disparage “the government” even as they run for an office in which they would be part of, yes, running the government.

Often, what they’re referring to is what we, as scholars of the inner workings of democracy, call “the administrative state.” At times, these critics use a label of collective distrust and disapproval for government workers that sounds more sinister: “the deep state.”

Most people, however, don’t know what government workers do, why they do it or how the government selects them in the first place.

Our years of research about the people who work in the federal government finds that they care deeply about their work, aiding the public and pursuing the stability and integrity of government.

Most of them are devoted civil servants. Across hundreds of interviews and surveys of people who have made their careers in government, what stands out most to us is their commitment to civic duty without regard to partisan politics.

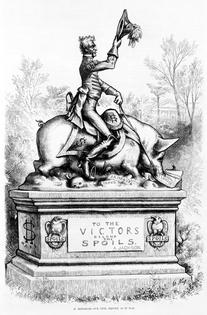

From the country’s founding through 1883, the U.S. federal government relied on what was called a “spoils system” to hire staff. The system got its name from the expression “to the victor goes the spoils.” A newly elected president would distribute government jobs to people who helped him win election.

This system had two primary defects: First, vast numbers of federal jobholders could be displaced every four or eight years; second, many of the new arrivals had no qualifications or experience for the jobs to which they were appointed.

Problems resulting from these defects were smaller than modern Americans might expect, because at that time the federal government was much smaller than it is today and had less to do with Americans’ everyday lives. This method had its defenders, including President Andrew Jackson, who believed that government tasks were relatively simple and anyone could do them.

But even so, the spoils system meant government was not as effective as it could have been – and as the people justifiably expected it to be.

In 1881, President James Garfield was assassinated by a man who believed he deserved a government job because of his support for Garfield but didn’t get one. The assassination led to bipartisan passage in Congress of the Pendleton Act of 1883.

...continued

Comments