Critical Race Theory is No Excuse for Ignorance

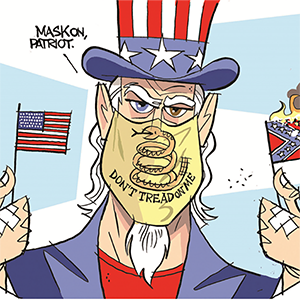

Political campaign season may be over but battles against what increasingly is being called “critical race theory” are not.

I still put CRT in quotes. I know that those who want to kick CRT out of public schools hate to hear me bring up the fact that CRT isn’t taught in public schools.

But that technicality doesn’t matter to the activists, including some genuinely concerned parents. True, CRT is an academic framework, created by progressive legal scholars in the 1970s and ’80s, that posits racism to be not only a matter of individual bias but also embedded in legal systems and policies that historically have shaped American law and public policy.

Yet, I’ve heard that label politically repurposed by conservatives and ballyhooed effectively through conservative media to apply to just about any publication or classroom instruction that, in their terms, “divides the races into ‘victims’ and ‘oppressors,’” or otherwise “might cause white children to feel badly about themselves.”

That’s not accurate, either, but it is the description I widely hear from advocates for laws like those already enacted in 12 states and proposed in 29 others, according to an Education Week analysis at the end of last month.

Since June 1, the Chicago-based American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom has tracked 155 incidents across the country and has provided support and consultation in 120 of those cases, office director Deborah Caldwell-Stone told me.

“That was just from July 1 to the first weeks of September,” she said, “compared to last year when we received 153 for the entire year.”

“What we’re seeing is challenges, particularly of books for young people, under the claim that they are critical race theory, but more often than not they are age-appropriate, developmentally appropriate books for young people dealing with Black American history or racism — and often being removed against (anti-censorship) policy.”

Back when the anti-CRT crusade was catching fire last spring, I said I couldn’t wait to see what happens when Black History Month rolls around. That’s because I found that most of the anti-CRT culture warriors I asked couldn’t really define what CRT is. They only knew that it was “bad,” didn’t belong in our schools and maybe cited a conservative website or cable TV commentator to back up their point.

Then voters in Virginia turned Democrat Terry McAuliffe’s early lead into a stunning loss to Republican Glenn Youngkin in the race for governor. A central issue in the contest was CRT and how children are being educated. , I realized — as McAuliffe did, too late — that whether anti-CRT individuals could define CRT accurately didn’t matter. The issue that grabbed their hearts and won their votes was simply how well their children were being educated — or not.

There’s a lesson there for Democrats. What voters know matters less than how you make them feel. McAuliffe’s effort to paint the mild-mannered Youngkin as another Donald Trump failed miserably. As election analysts say, McAuliffe had a messaging problem. Future Democratic candidates take note.

Meanwhile, in state governments and local school boards, anti-CRT campaigns, fueled by brisk social network traffic, pose a threat to academic freedom and informed education about people of color, LGBTQ people and other marginalized groups.

It struck me as ominous, for example, that the first complaint filed under Tennessee’s new anti-CRT law targeted a book about Martin Luther King Jr.

The Williamson County chapter of the conservative parents group Moms for Liberty complained that the book about King and his historic March on Washington was part of a set that promoted “Anti-American, Anti-White and Anti-Mexican teaching” in the district south of Nashville.

In a similar spirit, a York, Pennsylvania, school district sparked student protests by striking books on race, history and social justice — books about Rosa Parks, “Sesame Street” and the biography of education activist Malala Yousafzai.

And back in Illinois, a high school district school board meeting in suburban Downers Grove turned raucous as some Proud Boys joined parents and others to call for removal of the award-winning “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe from the district’s library shelves.

Those who spoke up to defend the book, which is not part of the assigned curriculum, reportedly outnumbered its detractors, I was relieved to learn. I haven’t read the book yet but I am heartened to hear about students who want to read something more than their text messages.

The best response to controversial speech, according to an old maxim, is more speech. I feel the same way about good, age-appropriate books. There’s a big diverse world those kids are about to take over. We don’t do them any favors by keeping them in ignorance about it.

========

(E-mail Clarence Page at cpage@chicagotribune.com.)

©2021 Clarence Page. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

(c) 2021 CLARENCE PAGE DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE MEDIA SERVICES, INC.