Weather

/Knowledge

Disturbance in central Atlantic could develop near Caribbean islands

After a brief lull in storms forming in the Atlantic, forecasters are watching a disturbance nearing the eastern Caribbean Sea that could develop while it moves in a general direction over the Caribbean islands.

An “area of disturbed weather” over the central tropical Atlantic Ocean is forecast to interact with a tropical wave that is ...Read more

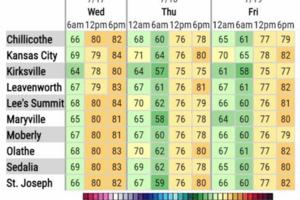

Scattered thunderstorms, damaging winds and dangerous heat loom for Kansas City area

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — A mix of summertime weather is expected in the Kansas City area in the coming days, ranging from the potential for scattered thunderstorms and dangerous heat, according to the National Weather Service.

“Widely scattered storms possible Friday through Sunday,” the weather service said in its forecast discussion. While ...Read more

Florida has highest number of heat-related illnesses in the nation, new report finds

Florida’s record hot summers can be dangerous for some people and a new study puts numbers to just how dangerous those soaring temperatures can be.

The Sunshine State leads the country in the number of emergency room and hospital visits from heat illness and has more than six million at-risk residents and outdoor workers, according to a ...Read more

South Florida is again under a heat advisory. This time, temperatures will feel up to 105

MIAMI — The oppressive heat will continue to bear down on South Florida as the National Weather Service rolled out another heat advisory, this one lasting until 7 p.m. Thursday.

The NWS warned that “feels-like” temperatures could reach up to 102-105 degrees across Broward and Miami-Dade counties, with a 20% chance of rain. The high ...Read more

Death Valley heat melts skin off a man's feet after he lost his flip-flops in the dunes

How hot was it in Death Valley over the weekend?

It was so hot that a European tourist melted the skin off his feet when he lost his flip-flops in the sand dunes, park officials said.

To make matters worse, the temperatures made the air too thin for a helicopter to fly in and help him.

The experience of the tourist, whose name was not ...Read more

Tropical moisture mixes with California's heat, driving storms, flood potential, fire risks

California's latest heat wave has drawn tropical moisture into the region, causing severe thunderstorms in some inland areas that forecasters warn could continue to cause flash flooding and dangerous lightning through at least Wednesday night.

The Sierra Nevada and surrounding foothills have the highest risk for severe thunderstorms Wednesday, ...Read more

'Long-duration' heat wave again cooking California, raising health and wildfire concerns

LOS ANGELES — Another bout of prolonged heat has kicked off across California and much of the West, expected to again bring several days of triple-digit temperatures to most inland areas.

July's second major heat wave isn't forecast to be as extreme as the last event, which set several all-time records for high temperatures. Nevertheless, the...Read more

Excessive heat warnings in effect for desert and mountain communities in Southern California

An excessive heat warning was issued Saturday for Southern California’s inland and desert communities, with triple-digit temperatures forecast through next week, bringing an elevated fire risk to some areas, according to the National Weather Service.

Portions of Los Angeles County, including Palmdale and Lancaster, as well as smaller towns in...Read more

Houston utility slammed over fumbled response to Beryl power outages

Thousands of people in the Houston area were still without power more than a week after Hurricane Beryl tore through the fourth-largest U.S. city. Two factors are now emerging as important explanations for why the powerful but predictable storm caused so much disruption: a shortage of workers at CenterPoint Energy Inc., Houston's main utility, ...Read more

Heat islands are making Vegas' summer more extreme, research shows

LAS VEGAS — Desert summers are getting more severe, and Las Vegas’ urban planning isn’t doing it any favors. Sprawl across the valley ensures that heat isn’t felt equally in every neighborhood.

This phenomenon is known as urban heat island effect, where dark-colored city streets and buildings trap excess heat, especially in areas ...Read more

A plume of Saharan dust is headed toward South Florida. Here's what to expect

MIAMI — A large plume of Saharan dust is heading to South Florida this weekend, forecasters say. And while the dust can tamp down the rain, it can hamper those with allergies and respiratory issues and potentially lead to higher temperatures in an already scalding summer.

This is the second round of dust, coming after plumes hit at the end of...Read more

Las Vegas on track for hottest summer on record

LAS VEGAS — How much hotter can it get? Just maybe we don’t want to find out.

Early Wednesday, the National Weather Service issued an “excessive heat watch” for Southern Nevada from Saturday morning to Sunday evening. The agency warned of “dangerously hot conditions,” with temperatures between 110 and 115 degrees in the valley.

...Read more

Another round of relentless, hazardous heat forecast across the West

LOS ANGELES — Another round of significant heat across California's interior is expected to bring potentially dangerous conditions back to the state, with weather officials warning of "relentless" heat risk over the Southwest beginning this weekend.

The National Weather Service warned of a mid-July heat wave building across the western United...Read more

Break from dangerous heat arrives in Kansas City. How long will this cool weather last?

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Cooler temperatures are expected in the Kansas City area over the next few days, giving the metro a break from the sweltering heat.

“Pleasant weather conditions are expected today and through Friday, with below normal temperatures and lower humidity,” the National Weather Service in Kansas City said on X, formerly ...Read more

As O'Hare sheltered in place during storm, passengers rode the winds out aboard planes: 'It felt very vulnerable'

As Andrea Jack sat in a plane at O’Hare International Airport on Monday evening, she felt as though she were flying.

The problem — the plane hadn’t left the ground.

The 45-year-old was stuck on the aircraft as severe thunderstorms, and what is being investigated as potential tornados, swept the Chicago metro area, including at O’Hare. ...Read more

Heavy rains soak St. Louis region, force hundreds to flee threatened dam in Southern Illinois

NASHVILLE, Ill. — Heavy rains on Tuesday forced the evacuation of hundreds of residents of Nashville, Illinois, as floodwaters here threatened to overwhelm an 89-year-old earthen dam.

While the barrier held fast, authorities planned to keep a cautious eye on the continuing downpour overnight.

The Washington County Emergency Management Agency...Read more

11K without power after storms but relief coming to Metro Detroit

DETROIT — Clusters of Metro Detroit residents are without power after another round of storms on Monday night, but the National Weather Service projects some relief ahead this week with cooler temperatures in store.

A total of 11,818 DTE Energy customers were without power as of 2 p.m.. Of those, more than 1,000 homes in Dearborn were ...Read more

California's grid passed the reliability test this heat wave. It's all about giant batteries

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — California’s power grid emerged from a nearly three weeklong record-setting heat wave relatively unscathed, and officials are crediting years of investment in renewable energy — particularly giant batteries that store solar power for use when the sun stops shining.

“This was a good early test that we passed in very ...Read more

Las Vegas haze, humidity may be joined by 110-degree heat today

LAS VEGAS — Southern Nevadans awoke to a hazy and humid Tuesday that may produce a second 110-degree daily high temperature.

A morning low of 91 just after 6 a.m. was combining with 23 percent humidity to make for sticky conditions.

The forecast called for the haze to be fairly widespread around the noon hour with calm winds.

“We never ...Read more

Hot weather is more dangerous than you think, experts say

Jonathan Bethly was upbeat as he helped his friend clean out some storage units for extra cash on a hot summer day, laughing and joking as he worked.

He later went to take a nap in his friend’s Cobb County apartment and never woke up, relatives said.

The county medical examiner’s office concluded the cause of death was asthma-related, and ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Florida has highest number of heat-related illnesses in the nation, new report finds

- Death Valley heat melts skin off a man's feet after he lost his flip-flops in the dunes

- South Florida is again under a heat advisory. This time, temperatures will feel up to 105

- Scattered thunderstorms, damaging winds and dangerous heat loom for Kansas City area

- Tropical moisture mixes with California's heat, driving storms, flood potential, fire risks