Climate change threatens the Winter Olympics’ future – and even snowmaking has limits for saving the Games

Published in Science & Technology News

Watching the Winter Olympics is an adrenaline rush as athletes fly down snow-covered ski slopes, luge tracks and over the ice at breakneck speeds and with grace.

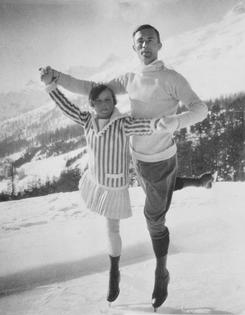

When the first Olympic Winter Games were held in Chamonix, France, in 1924, all 16 events took place outdoors. The athletes relied on natural snow for ski runs and freezing temperatures for ice rinks.

Nearly a century later, in 2022, the world watched skiers race down runs of 100% human-made snow near Beijing. Luge tracks and ski jumps have their own refrigeration, and four of the original events are now held indoors: figure skaters, speed skaters, curlers and hockey teams all compete in climate-controlled buildings.

Innovation made the 2022 Winter Games possible in Beijing. Ahead of the 2026 Winter Olympics in northern Italy, where snowfall was below average for the start of the season, officials had large lakes built near major venues to provide enough water for snowmaking. But snowmaking can go only so far in a warming climate.

As global temperatures rise, what will the Winter Games look like in another century? Will they be possible, even with innovations?

The average daytime temperature of Winter Games host cities in February has increased steadily since those first events in Chamonix, rising from 33 degrees Fahrenheit (0.4 Celsius) in the 1920s-1950s to 46 F (7.8 C) in the early 21st century.

In a recent study, scientists looked at the venues of 19 past Winter Olympics to see how each might hold up under future climate change.

They found that by midcentury, four former host cities – Chamonix; Sochi, Russia; Grenoble, France; and Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany – would no longer have a reliable climate for hosting the Games, even under the United Nations’ best-case scenario for climate change, which assumes the world quickly cuts its greenhouse gas emissions. If the world continues burning fossil fuels at high rates, Squaw Valley, California, and Vancouver, British Columbia, would join that list of no longer being a reliable climate for hosting the Winter Games.

By the 2080s, the scientists found, the climates in 12 of 22 former venues would be too unreliable to host the Winter Olympics’ outdoor events; among them were Turin, Italy; Nagano, Japan; and Innsbruck, Austria.

In 2026, there are now five weeks between the Winter Olympics and the Paralympics, which last through mid-March. Host countries are responsible for both events, and some venues may increasingly find it difficult to have enough snow on the ground, even with snowmaking capabilities, as snow seasons shorten.

Ideal snowmaking conditions today require a dewpoint temperature – the combination of coldness and humidity – of around 28 F (-2 C) or less. More moisture in the air melts snow and ice at colder temperatures, which affects snow on ski slopes and ice on bobsled, skeleton and luge tracks.

As Colorado snow and sustainability scientists and also avid skiers, we’ve been watching the developments and studying the climate impact on the mountains and winter sports we love.

The Earth’s climate will be warmer overall in the coming decades. Warmer air can mean more winter rain, particularly at lower elevations. Around the globe, snow has been covering less area. Low snowfall and warm temperature made the start to the 2025-26 winter season particularly poor for Colorado’s ski resorts.

However, local changes vary. For example, in northern Colorado, the amount of snow has decreased since the 1970s, but the decline has mostly been at higher elevations.

A future climate may also be more humid, which affects snowmaking and could affect bobsled, luge and skeleton tracks.

Of the 16 Winter Games sports today, half are affected by temperature and snow: Alpine skiing, biathlon, cross-country skiing, freestyle skiing, Nordic combined, ski jumping, ski mountaineering and snowboarding. And three are affected by temperature and humidity: bobsled, luge and skeleton.

Developments in technology have helped the Winter Games adapt to some changes over the past century.

Hockey moved indoors, followed by skating. Luge and bobsled tracks were refrigerated in the 1960s. The Lake Placid Winter Games in 1980 in New York used snowmaking to augment natural snow on the ski slopes.

Today, indoor skiing facilities make skiing possible year-round. Ski Dubai, open since 2005, has five ski runs on a hill the height of a 25-story building inside a resort attached to a shopping mall.

Resorts are also using snowfarming to collect and store snow. The method is not new, but due to decreased snowfall and increased problems with snowmaking, more ski resorts are keeping leftover snow to be prepared for the next winter.

But making snow and keeping it cold requires energy and water – and both become issues in a warming world. Water is becoming scarcer in some areas. And energy, if it means more fossil fuel use, further contributes to climate change.

The International Olympic Committee recognizes that the future climate will have a big impact on the Olympics, both winter and summer. It also recognizes the importance of ensuring that the adaptations are sustainable.

The Winter Olympics could become limited to more northerly locations, like Calgary, Alberta, or be pushed to higher elevations.

The Summer Games also face challenges. Hot temperatures and high humidity can make competing in the summer difficult, but these sports have more flexibility than winter sports.

For example, changing the timing of typical summer events to another season can help alleviate excessive temperatures. The 2022 World Cup, normally a summer event, was held in November so Qatar could host it.

What makes adaptation more difficult for the Winter Games is the necessity of snow or ice for all of the events.

In uncertain times, the Olympics offer a way for the world to come together.

People are thrilled by the athletic feats, like Jean-Claude Killy winning all three Alpine skiing events in 1968, and stories of perseverance, like the 1988 Jamaican bobsled team competing beyond all expectations.

The Winter Games’ outdoor sports may look very different in the future. How different will depend heavily on how countries respond to climate change.

This updates an article originally published Feb. 19, 2022, with the 2026 Winter Games.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Steven R. Fassnacht, Colorado State University and Sunshine Swetnam, Colorado State University

Read more:

Olympic skiers and snowboarders are competing on 100% fake snow – the science of how it’s made and how it affects performance

As the Milan Winter Olympics approach, what are the environmental expectations?

Geopolitics will cast a long shadow over the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympic Games

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments