New York City greenlights congestion pricing – here’s how this toll plan is expected to improve traffic, air quality and public transit

Published in Science & Technology News

New York City is poised to launch the first congestion pricing plan to reduce traffic in a major U.S. metropolitan area. Like many journeys in the Big Apple, this one has been punctuated by delays. Once the system starts up, however, it’s expected to significantly reduce gridlock in Manhattan and generate billions of dollars to improve public transit citywide.

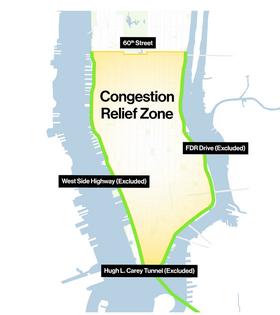

The basic idea is simple. To enter the Congestion Relief Zone, which covers Manhattan south of 60th Street, large trucks will pay $36, small trucks $24, passenger vehicles $15 and motorcycles $7.50. Ride-share vehicles and taxis will pay $2.50 and $1.25, respectively. Peak hours run from 5 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekdays and 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekends; overnight tolls are discounted by 75%.

Evidence from cities around the world shows that charging motorists fees for driving into city centers during busy periods is a rarity in urban public policy: a measure that works and is cost-effective. Congestion pricing has succeeded in cities including London, Singapore and Stockholm, where it has eased traffic, sped up travel times, reduced pollution and provided funds for public transportation and infrastructure investments.

As an urban policy scholar, I’m looking forward to seeing New York’s plan go into effect. There may well be surprises and adjustments as officials see how it works in practice. But given the heavy costs that traffic imposes on public health and productivity, I’m encouraged to see a major U.S. city finally test this approach.

Congestion pricing is a response to externalities – costs or benefits that are generated by one party but incurred by another. Clogged city streets and air pollution are externalities created by urban car users, many of whom live outside the city.

This concept has been around for some time. British economist Arthur Pigou discussed it as early as 1920 as part of his attempt to remedy the suboptimal workings of the market system. In Pigou’s view, taxing harmful activities would discourage people from engaging in them.

Other thinkers took up this idea. In 1963, Canadian economist William Vickrey, a future Nobel laureate, argued that roads were scarce resources that needed to be valued by imposing costs on users.

This approach is behind behavioral economics, the policy strategy of using “nudges” that preserve choice but encourage certain actions. Congestion pricing assumes that increased prices will make people heading into New York think more carefully about their travel patterns, and about alternatives to driving.

Congestion pricing in a city a big as New York is no small step. The New York plan was presented to the board of the Metropolitan Transit Authority in November 2023 after years of study and a detailed environmental impact assessment, required by federal law.

Project sponsors, which include several city agencies and the state transportation department, stated in the impact assessment that on an average weekday, an estimated 1.86 million people entered lower Manhattan by motor vehicle. Travel speeds in Manhattan’s central business district, below 60th Street, declined by 23% between 2010 and 2019, from 9.1 to 7.1 mph. The traffic was generating air and noise pollution, wasting travelers’ time, increasing business costs and preventing emergency vehicles from responding quickly to accidents.

The agencies estimated that the proposed toll system would reduce traffic in the Congestion Relief Zone by 17%, with an associated decline in air pollution. It also would generate US$15 billion for capital improvements to the city’s public transit system, including making stations accessible for passengers with disabilities and buying new electric buses and commuter rail and subway cars.

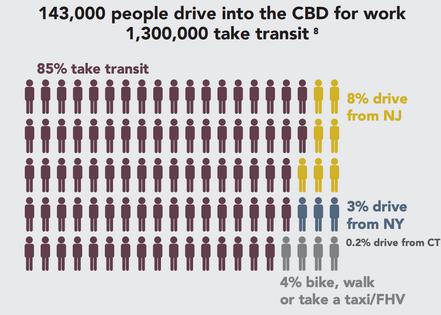

More than 75% of all trips into the central business district are made by public transit. The system has been plagued by breakdowns over the past decade. The Metropolitan Transit Authority recently adopted a $52 billion capital improvement program to update its network, some parts of which are more than 100 years old.

Over several months of public hearings, the MTA heard both broad support for congestion pricing and thousands of requests for credits, discounts and exemptions, most of which were denied. The limited number of exemptions includes private commuter buses, school buses and city-owned vehicles, including emergency vehicles.

In addition, drivers who travel via Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive on Manhattan’s eastern edge, the West Side Highway on its western edge, or the Carey Tunnel between Brooklyn and Battery Park will not be charged if they do not enter any street in the Congestion Relief Zone. Drivers from the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island will be eligible for rebates and discounts on certain bridge tolls.

There were widespread complaints from New Yorkers in the outer boroughs of the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, and from car commuters who live outside of the city. New Jersey is suing the MTA, arguing among other things that the plan is unconstitutional because it burdens interstate commerce. This suit could delay the start of congestion pricing.

Nonetheless, the board adopted the plan with just one dissenting vote, from a representative of Nassau County on Long Island.

Many questions will only be answered once the system starts up in June 2024, or later if it is delayed by lawsuits. Will toll prices be high enough to spur people to switch to another mode of transportation or combine trips, while still generating enough revenue for the MTA’s ambitious capital improvement program? How will toll revenue be spent? And how will commuters respond when they find that trains and subways initially are more crowded, before capital upgrades improve the system?

Some low-income and minority communities that already experience heavy traffic, such as the Bronx, could see increased congestion as drivers detour around the toll zone. To help mitigate some of these effects, the transit authority is planning to invest millions of dollars to reduce pollution in these environmental justice areas through steps such as installing air filters in schools, planting more trees and electrifying trucks at the massive Hunts Point Food Distribution Center in the Bronx.

No one likes to pay for something that was previously free. But freedom for car users has imposed health and economic costs on millions of New Yorkers for many years. Congestion charges do raise equity issues, but only 5% percent of people who commute into the central business district travel by car, and most of those drivers have relatively high incomes.

The MTA may need to adjust tolls, the zone’s borders or other aspects of the plan. But if New York’s experiment succeeds, it could provide a model and valuable insights for other traffic-clogged U.S. cities.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: John Rennie Short, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Read more:

If all the vehicles in the world were to convert to electric, would it be quieter?

Ever-larger cars and trucks are causing a safety crisis on US streets – here’s how communities can fight back

City planners are questioning the point of parking garages

John Rennie Short does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments