Science & Technology

/Knowledge

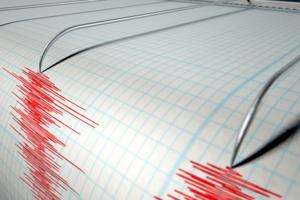

Earthquake swarm resumes to rattle Northern California city, seismologists say

A swarm of at least six earthquakes reaching up to magnitude 2.9 rattled San Ramon near San Francisco, the U.S. Geological Survey reports.

The other quakes in the Saturday, Dec. 13, swarm ranged from magnitude 1.3 to 2.3, according to the USGS.

San Ramon earlier was hit by a swarm of more than 90 quakes starting Nov. 9, The Sacramento Bee ...Read more

Weather might cause issues, but ULA, SpaceX could fly 3 launches within 12 hours

Dicey weather could cause issues, but three rockets from SpaceX and United Launch Alliance are lined up to launch from the Space Coast beginning Sunday night that could set a record with three Florida-based missions launched within 12 hours.

Up first is a SpaceX Falcon 9 on the Starlink 6-82 mission with 29 Starlink satellites from Cape ...Read more

Scientists warn federal funding cuts could undermine walleye recovery in Minnesota

Christopher Rounds is a scientist who studies walleye in Minnesota, but he doesn’t use a boat or a net or even a laboratory.

“I probably go outside like five times a year and sit behind a computer the rest of the time,” says the University of Minnesota graduate student and researcher at the Midwest Climate Adaptation Science Center (MW ...Read more

Weather pushes ULA launch, but SpaceX still has Sunday, Monday launches on tap

Dicey weather already pushed United Launch Alliance to delay a planned early Monday launch of an Atlas V, but SpaceX has a pair of Falcon 9 rockets that could fly Sunday night and Monday morning.

Up first is a SpaceX Falcon 9 on the Starlink 6-82 mission with 29 Starlink satellites from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch ...Read more

Ancient lake from ice age comes back to life in Death Valley after record rainfall

Between 128,000 and 186,000 years ago, when ice covered the Sierra Nevada, a lake 100 miles long and 600 feet deep sat in eastern California in what is now the Mojave Desert.

As the climate warmed and the ice retreated, the lake dried up, leaving a white salt pan in its place.

But a November of record rainfall has brought the ancient lake, ...Read more

Some big water agencies in farming areas get water for free. Critics say that needs to end

LOS ANGELES — The water that flows down irrigation canals to some of the West’s biggest expanses of farmland comes courtesy of the federal government for a very low price — even, in some cases, for free.

In a new study, researchers analyzed wholesale prices charged by the federal government in California, Arizona and Nevada, and found ...Read more

Rare, deep-sea encounter: California scientists observe 'extraordinary' seven-arm octopus

Almost a half-mile below the surface of Monterey Bay, California, scientists recently recorded rare footage of a seven-arm octopus— only the fourth time the same research team has spotted the species in about four decades.

In a new video posted online, scientists with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute shared footage of the giant ...Read more

SpaceX sets $800 billion valuation, confirms 2026 IPO plans

SpaceX has authorized an insider share sale that values Elon Musk’s rocket and satellite maker at about $800 billion, according to a company message seen by Bloomberg on Friday.

The company also said it’s preparing for a possible public offering in 2026, a deal aimed at funding an “insane flight rate” for its developmental Starship ...Read more

Eroded Jersey Shore beaches could soon get federal money for replenishment. Will it be enough?

Congress appears poised to spend money in 2026 on beach replenishment projects in wake of the zero dollars it allocated this year.

But bills proposed in the House by U.S. Rep. Chuck Fleischmann, R-Tenn., and in the Senate by U.S. Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., appear to still fall woefully short of what’s needed, a coastal advocacy group says. U.S...Read more

As Florida offshore drilling looms, birds less protected from spills under Trump

TAMPA, Fla. — Richard Baker remembers the feathers: bright white and striking.

Just 20 days earlier, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig had exploded, killing 11 people and igniting one of the worst environmental disasters in modern history. A pelican and a Northern gannet were the first two birds plucked by wildlife rescuers from the oily waters ...Read more

Podcast industry under siege as AI bots flood airways with thousands of programs

Chatty bots are sharing their hot takes through hundreds of thousands of AI-generated podcasts. And the invasion has just begun.

Though their banter can be a bit banal, the AI podcasters' confidence and research are now arguably better than most people's.

"We've just begun to cross the threshold of voice AI being pretty much indistinguishable ...Read more

Colorado wolf re-released in Grand County after crossing into New Mexico

DENVER — Colorado Parks and Wildlife re-released a wolf into Grand County this week after it had traveled into New Mexico, according to a news release.

The New Mexico Department of Game and Fish captured gray wolf 2403 and returned the animal to Colorado.

Colorado wildlife officials decided to release the wolf in Grand County yesterday ...Read more

In search for autism's causes, look at genes, not vaccines, researchers say

Earlier this year, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. pledged that the search for autism's cause — a question that has kept researchers busy for the better part of six decades — would be over in just five months.

"By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic, and we'll be able to eliminate those ...Read more

California Coastal Commission approves land deal to extend last nuclear plant through 2030

California environmental regulators on Thursday struck a landmark deal with Pacific Gas & Electric to extend the life of the state’s last remaining nuclear power plant in exchange for thousands of acres of new land conservation in San Luis Obispo County.

PG&E’s agreement with the California Coastal Commission is a key hurdle for the Diablo ...Read more

SpaceX launches 1st of 5 missions on tap in next 8 days on Florida's Space Coast

ORLANDO, Fla. — SpaceX and United Launch Alliance are combining for a busy week of rocket launches on the Space Coast.

First up Thursday evening was SpaceX’s planned Starlink 6-90 mission with 29 Starlink satellites from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch Complex 40 at 5:01 p.m. Eastern time.

This was the 16th flight of ...Read more

California extends red abalone fishing ban for another 10 years

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — The California Fish and Game Commission voted Thursday to extend the closure of the recreational red abalone fishery for another decade, keeping the ban in place until April 2036.

The fishery has been closed since 2018, when the commission shut it down in response to a dramatic population decline along Northern California...Read more

Hopkins neurologist designed artificial intelligence to work like a human brain

BALTIMORE — Artificial intelligence systems designed to physically imitate natural brains can simulate human brain activity before being trained, according to new research from Johns Hopkins University.

“The work that we’re doing brings AI closer to human thinking,” said Mick Bonner, who teaches cognitive science at Hopkins. “What I ...Read more

Toxic water from Texas oil production is set to be treated and pumped into rivers

Texas is about to deploy a potential solution to the oil industry’s toxic wastewater problem — but it’s a move that carries environmental risks of its own.

State regulators are working to issue permits that would let four companies, including major landowner Texas Pacific Land Corp. and pipeline operator NGL Energy Partners LP, release ...Read more

Instacart is charging different prices to different customers in a dangerous AI experiment, report says

The grocery delivery service Instacart is using artificial intelligence to experiment with prices and charge some shoppers more than others for the same items, a new study found.

The study from nonprofits Groundwork Collaborative and Consumer Reports followed more than 400 shoppers in four cities and found that Instacart sometimes offered as ...Read more

'Nothing beautiful about that': Erase Trump's face from parks pass, lawsuit demands

Calling the design decision crass and disgusting as well as illegal, an environmentalist group is demanding that President Trump’s image be removed from the 2026 national parks pass.

A lawsuit filed Wednesday, Dec. 10, by the Center for Biological Diversity takes issue with an Interior Department switch-up that replaced the contest-winning ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Earthquake swarm resumes to rattle Northern California city, seismologists say

- Ancient lake from ice age comes back to life in Death Valley after record rainfall

- Weather pushes ULA launch, but SpaceX still has Sunday, Monday launches on tap

- Weather might cause issues, but ULA, SpaceX could fly 3 launches within 12 hours

- Scientists warn federal funding cuts could undermine walleye recovery in Minnesota