How to make Michael Twitty's matzoh ball gumbo, a soup of Black and Jewish cuisines

Published in Variety Menu

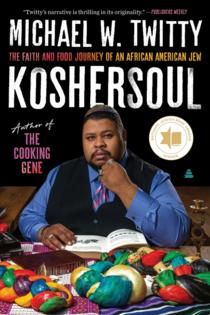

LOS ANGELES -- With a rainbow knitted kippah affixed to the crown of his head, Michael Twitty is paced and intentional as he moves through the test kitchen at the L.A. Times. He's here to make one of his classic Passover dishes, matzoh ball gumbo, which combines two recipes from his food memoir "Koshersoul."

The crimson stew adds buoyant, scallion-studded matzoh balls to a heartening okra gumbo, joining two staple dishes from Jewish and Black Southern cuisines. Chicken broth and diced tomatoes lend the finished gumbo their umami, with a Creole spice blend that imparts a gentle, humming heat.

Twitty, who hails from the Washington, D.C., area, says he's always wanted to winter in Los Angeles. He's been living at the junction of Beverly Hills, Pico-Robertson and West Hollywood since November and, following a short trip back to the East Coast in March, plans to stay through June.

After hosting a conversation at chef Martin Draluck's Black Pot Supper Club series in February, Twitty will take over the kitchen at Baldwin Hills' Post & Beam restaurant with his "Koshersoul" dinner pop-up on Wednesday, May 15. The evening will include back-to-back dinners with recipes from the book. The first service will lean into Twitty's Jewish background with West African brisket and peach rice kugel, as well as matzoh ball gumbo. The second will embrace a cookout vibe with the same brisket plus barbecue chicken and lamb (all of the meat will be kosher), baked beans and collard green lox wraps.

"Koshersoul," the follow up to his James Beard Award-winning "The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History," details Twitty's journey as a Black, gay and Jewish man and draws meaningful links between Afro-Atlantic and global Jewish culinary practices, including the contributions of Jews of color. It was named the 2023 book of the year at the National Jewish Book Awards, making Twitty the first Black author to win the distinction. Currently, Twitty is working on a cookbook with essential recipes from the American South and has plans to write another food memoir and history that will serve as a queer journey through the culinary world.

He credits food historian Marcie Cohen Ferris for inspiring the matzoh ball gumbo recipe. Published in 2010, Ferris' book "Matzoh Ball Gumbo" explores the historic foodways of Southern Jews, including the influence of Black Southerners and Black women in particular.

"When I make this dish, I'm thinking how can we connect to that past and history, and recount the people who were often nameless?" says Twitty. He says that for European Jews assimilating in the Deep South in the early and mid 20th century, food, often prepared by Black domestic workers, was a conduit for belonging.

Rather than a blending or "fusion" of culinary styles, Twitty sees his matzoh ball gumbo as an act of preservation. It's a continuation of Southern food stories, highlighting the traditions that extend across the African and Jewish diasporas.

"You can compare it to soup and dumplings from Jamaica, or omo tuo from Ghana," he says. "In West and Central Africa, the main meal is often a soup, sauce or stew with a starch — sauce and fufu, sauce and banku, sauce and millet or rice balls. There are so many parallels there."

He continues, saying that, "Jewish tradition is extremely fluid and flexible. We eat foods that have their roots in very ancient ideas, but bear very little resemblance to their original concept."

Twitty begins by methodically chopping the herbs and vegetables for his gumbo and matzoh balls: parsley, green onions, garlic and the "holy trinity" of onion, celery and bell pepper.

Next, he makes the dough for the matzoh balls. Cooking alongside Twitty reminds me of sharing kitchen space with my late great-grandmother Madea, a born-and-raised Mississippian. Like her, he measures in pinches, makes last-minute adjustments (such as substituting salt for baking powder in the matzoh ball dough) and gives a deep, satisfied grunt when his taste-testing yields the desired results.

Once the matzoh ball dough is finished, Twitty seals the bowl with plastic wrap and puts it in the refrigerator to rest.

As he slices the okra into razon-thin rounds, our conversation winds from the Yiddish words for matzoh ball and Passover (kneidlach and Pesach, respectively) to his experiences traveling to Italy and various countries in West Africa.

We're weeks away from Passover, but the atmosphere feels similar to a Seder Twitty might host. The conversation is peppered with laughter, and topics that are usually avoided at the dinner table — namely, religion and politics — are met with curiosity and understanding. Such discussions, Twitty says, are integral to the spirit of Passover. He describes a long history of Seders that supported early labor movements, women's rights and Black and Jewish liberation.

"It's exactly what Pesach is supposed to do, which is open those gates of liberation and lack of constraints to the rest of humanity," he says. "It can be both an origin story moment for the Jewish people, and a human liberation story for all of mankind. It was always meant to be that way."

Twitty pauses to give the roux his full attention. He stirs slowly, peeking into the deep-bottomed pot to gauge its progress. The potato starch that he uses instead of flour takes longer to brown, about 15 minutes. Twitty dips a spoon in to taste; his throaty purr tells us that it's ready for more broth.

After adding the cooked vegetables, tomatoes, okra, thyme and Creole seasoning, we let the concoction simmer and turn our attention back to the matzoh balls. We fill a large pot with salted water and wait for it to reach a rolling boil. Twitty shapes the dough into walnut-sized spheres.

One by one, the matzoh balls get dropped into the pot with boiling water. In a departure from the recipe in his book, Twitty takes them out early and transfers them to the gumbo, where he lets them simmer under a lid for an additional 15 minutes.

Finally, we ladle the gumbo into bowls, at least two or three matzoh balls per serving. The okra retains a pleasant crunch and the matzoh balls are savory, a persuasive replacement for rice or even chicken. Someone notes the rare silence that has befallen the kitchen — this gumbo is good.

There are several of us in the kitchen, and Twitty's gumbo speaks to different parts of each of our heritages. For me, the okra and tomato-rich broth recalls my maternal Mississippi roots, while the matzoh balls take someone else back to childhood experiences making them alongside their Bubbe.

"We have to remember that we co-created the Southern culture with Indigenous people, with white people, with immigrants from all over the world," Twitty says. "And all of those stories have to be told for it to be a true, full and honest recounting of how we got here, and what mistakes we should refuse to make going forward."

____

Find Michael Twitty at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on Sunday, April 21, at Booth 410, where he'll have signed copies of "Koshersoul" available to purchase, 2-3 p.m. Tickets are available for Twitty's "Koshersoul" dinner pop-up at Post & Beam on Wednesday, May 15, and can be purchased via Eventbrite .

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments