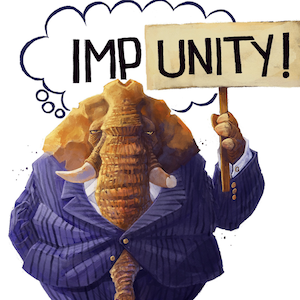

Footage, documents at odds with DHS accounts of immigration enforcement incidents

Published in News & Features

As a growing number of encounters between civilians and Department of Homeland Security agents — including the widely scrutinized fatal shooting of Renee Good in Minneapolis — are scrutinized in court records and on social media, federal officials are returning to a familiar response: self-defense.

In more than a handful of recent encounters, the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection, has said its agents acted in self-defense during violent encounters, even as eyewitness testimony and video footage raised questions about whether those accounts fully matched what happened.

And in a ruling for a recent civil lawsuit, a U.S. district judge said federal immigration officials were not forthcoming about enforcement efforts, citing discrepancies between official DHS statements and video evidence.

“We’re now in a situation in which official sources in the Trump administration are really tying themselves quite strongly to a particular narrative, regardless of what the widely disseminated videos suggest,” said César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, a law professor at Ohio State University.

The cases come amid an aggressive expansion of federal immigration enforcement and increasing scenes of violent and intimidating arrest tactics. President Donald Trump’s administration has sharply increased the hiring of immigration agents, broadened enforcement operations and accelerated deportations, as protests have spread across major cities.

The use of force, paired with conflicting official statements and evidence, has raised questions about whether federal immigration officials can be held accountable and highlighted the steep hurdles victims of excessive force might face in seeking legal recourse.

The Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement did not respond to multiple requests from Stateline for comment on discrepancies between official accounts and publicly available evidence.

Since last July, there have been at least 17 open-fire incidents involving federal immigration agents — including fatal shootings, shootings with injuries and cases in which shots were fired — according to data compiled by The Trace, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news outlet investigating gun violence. A recent Wall Street Journal investigation also found 13 incidents since July in which immigration agents fired at or into civilian vehicles.

One of the most prominent examples unfolded in Minneapolis this month: Good’s fatal shooting by a masked ICE agent. The Department of Homeland Security initially said the agent, Jonathan Ross, fired in self-defense after Good, 37, allegedly tried to run over officers. Videos taken by bystanders show Good’s vehicle reversed, shifted and began to turn away from officers after one yelled and pulled on her car handle. Ross positioned himself near the hood of her car, and he began firing.

Minnesota officials later stated the footage did not support DHS’ description of an imminent threat, prompting renewed scrutiny of how the Trump administration is characterizing use-of-force encounters.

Similar discrepancies have surfaced in other cases. The Department of Homeland Security recently revised its account of a December shooting in Glen Burnie, Maryland, after local police contradicted its initial version. DHS first claimed both men injured in the incident were inside a van that ICE officers fired at in self-defense, but later said that one of the injured men had already been arrested and was in custody inside an ICE vehicle when he was hurt. The other man was shot twice and is facing two federal criminal charges.

In August, federal immigration agents fired at a family’s vehicle three times in San Bernardino, California. DHS maintained the shooting was justified after at least two agents were struck by the vehicle, but available footage shows an agent breaking the driver-side window moments before gunfire erupted. Surveillance footage from the street does not show agents being struck by the vehicle.

“I can’t think of another time in my lifetime — I’m 50 years old — where we’ve seen this sort of force in the streets in the United States,” said Mark Fleming, the associate director of federal litigation at the National Immigrant Justice Center. Fleming has been an immigration and civil rights attorney for the past 20 years.

García Hernández, the law professor at Ohio State University, echoed Fleming’s point, saying that what also stands out is how often agents are deploying less‑lethal weapons in ways that would generally be prohibited — including firing rubber pellets and similar projectiles at people’s faces or heads.

In its use-of-force policy, DHS agents may use force only when no “reasonably effective, safe, and feasible” alternative exists and only at a level that is “objectively reasonable.” DHS policy emphasizes “respect for human life” and directs officers to be proficient in de-escalation tactics — using communication or other techniques to stabilize or reduce the intensity of a potentially violent situation without, or with reduced, physical force. The policy also states that deadly force should not be used solely to prevent the escape of a fleeing suspect.

ICE, as an agency under DHS, is bound by this guidance, but the policy on shooting at moving vehicles differs from what many law enforcement agencies nationwide now consider best practices. While DHS prohibits officers from firing at the operator of a moving vehicle unless it is necessary to stop a serious threat, its rules do not explicitly instruct officers to get out of the way of moving vehicles when possible.

Use of force

A growing pattern of aggressive tactics and conflicting evidence has raised serious questions about how federal immigration agents use lethal and less-lethal force, and how DHS officials describe the incidents to the public.

In September, 38-year-old Silverio Villegas González was fatally shot during a traffic stop in Franklin Park, a suburb near Chicago. DHS claimed that one agent was “seriously injured” after being dragged by González’s car as he tried to flee. But body-camera footage shows the agent telling a Franklin Park police officer that his injury was “nothing major.”

In a statement, DHS said the agent responded with lethal force because he was “fearing for his own life” — a narrative very similar to the department’s description of the fatal shooting of Good in Minneapolis.

In recent months, DHS officials have claimed that immigration agents have been repeatedly attacked with vehicles.

“We’ve seen vehicles weaponized over 100 times in the last several months against our law enforcement officers,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said during an interview with CNN this month.

In court filings related to a civil lawsuit about Operation Midway Blitz in Chicago, the department provided body-camera footage and other internal records to bolster their claims of self-defense.

But U.S. District Judge Sara Ellis found the evidence “difficult, if not impossible to believe.” In her lengthy opinion issued in late November, Ellis acknowledged that agents sometimes encountered aggressive drivers but also found that agents treated cars that were merely following them as potential threats.

In October, an ICE agent shot a community observer, Marimar Martinez, five times during a confrontation in Chicago. DHS claimed that she rammed the ICE vehicle with her car and boxed it in, but surveillance footage does not show the agents were trapped.

Martinez survived, but the Trump administration quickly labeled her a “domestic terrorist” — the same label used to describe Good. Martinez’s criminal charges were dropped in November after the federal Department of Justice abruptly moved to dismiss the case.

In Ellis’ ruling on the civil lawsuit, she wrote that federal officials “cannot simply create their own narrative of what happened, misrepresenting the evidence to justify their actions,” and that the violence used by federal agents “shocks the conscience,” a legal standard meaning a situation that seems grossly unjust to an observer.

Ellis also explicitly questioned the conduct and leadership of Greg Bovino of U.S. Border Patrol during the Chicago immigration operation. Bovino, who has led the administration’s big-city campaign, was deposed under oath, and in her November ruling, Ellis described him as “not credible,” writing that he “appeared evasive over the three days of his deposition, either providing ‘cute’ responses … or outright lying.”

In a footnote, Ellis also noted an instance in which an agent asked ChatGPT to draft a use-of-force report from a single sentence and a few images — further undermining the credibility of official DHS accounts.

A narrow path to accountability

Holding federal immigration agents accountable for misconduct is difficult, even as video evidence and police or court records increasingly contradict official government accounts.

With more evidence surfacing and legal claims already underway, some experts say it’s likely that even more lawsuits will emerge this year.

“We should expect to see more examples, more instances in which cellphone video is used to bolster legal claims against DHS, ICE, Border Patrol and specific officers as well,” said García Hernández, of Ohio State University.

Federal officers are shielded by legal doctrines such as qualified immunity and U.S. Supreme Court rulings that restrict when people can sue federal officials for constitutional violations. In recent years, the courts have narrowed the circumstances under which individuals can bring claims for excessive force or wrongful death.

Suing individual federal immigration agents is nearly impossible.

People can, however, pursue claims against the federal government under the Federal Tort Claims Act if a government employee causes financial or bodily harm. These cases, which can include claims for wrongful death, face significant hurdles: no punitive damages, no jury trials, state-specific caps on compensation and protections for discretionary government decisions.

Internal DHS investigations can lead to discipline or policy changes, but their findings may not be made public.

Several state lawmakers in California, Colorado, Georgia, New York and Oregon are pursuing measures that would allow residents to sue federal immigration agents for constitutional violations. Illinois has a similar law already in place, but this pathway remains largely untested, and experts say it faces significant legal and logistical hurdles.

____

Stateline reporter Amanda Watford can be reached at ahernandez@stateline.org.

____

©2026 States Newsroom. Visit at stateline.org. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments