NASA's attempt to bring home part of Mars is unprecedented. The mission's problems are not

Published in News & Features

NASA missions are managed by very smart people with established histories of doing very hard things. How does something as terrestrially mundane as budgeting continually trip them up?

"The problem is that the models that you have as a cost estimator — and they have very complex proprietary software models that attempt to understand these types of things — are all built on things that have happened, in the past tense," said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy for the Planetary Society.

"By definition, when you're trying something completely new, it's very hard to estimate in advance how much something unprecedented will cost," Dreier said. "That happened for Apollo, that happened for the space shuttle, it happened for James Webb, and it's happening now for Mars Sample Return."

Mars Sample Return also has some mission-specific challenges that Webb didn't have to contend with. For one, it's happening at the same time as Artemis, NASA's wildly expensive mission to return people to the moon.

Expected to cost $93 billion through 2025, Artemis got a 27% increase in its budget over the previous year, while Mars Sample Return's guaranteed funding is 63% less than last year's spend.

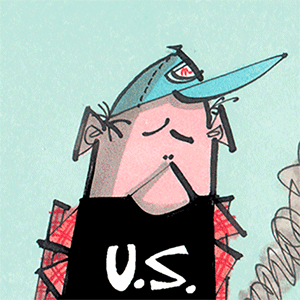

And while NASA's ambitions are growing, its funding from Congress, adjusted for inflation, has been essentially flat for decades. That leaves little room for unexpected extras.

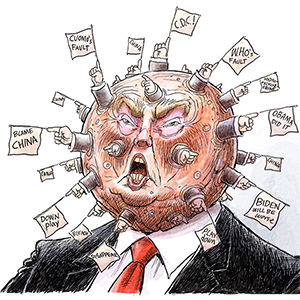

"We are tasking the space agency with the most ambitious slate of programs in space since the Apollo era, but instead of Apollo-era budgets, it has one-third of 1% of U.S. spending to work with," Dreier said. "If you stumble right now, the wolves will come for you. And that's what is happening to Mars Sample Return."

Not all ambitious scientific endeavors survive the kind of scrutiny the sample return is facing. In 1993 Congress canceled the U.S. Department of Energy's Superconducting Super Collider, an underground particle accelerator, citing concerns about rising costs and fiscal mismanagement. The government had already spent $2 billion on the project and dug 14 miles of tunnel.

But in the same week that Congress ended the supercollider, it agreed — by a margin of a single vote — to continue funding the International Space Station, a similarly expensive project whose cost overruns had been widely criticized. ISS launched in November 1998 and is still going strong. (For now, anyway — NASA will intentionally crash it into the sea in 2030.)

The space station's future was never seriously threatened again after that painfully close vote, just as Webb's future was never seriously questioned after the 2010 cancellation threat.

JPL, the institution managing Mars Sample Return, has already paid dearly for the mission's initial stumbles, laying off more than 600 employees and 40 contractors after NASA ordered it to reduce its spending.

But projects that survive this kind of reckoning often emerge "stronger and more resilient," Dreier said. "They know the eyes of the nation and NASA and Congress are on them, so you have to perform."

NASA is set to reveal this month how it plans to move forward with Mars Sample Return. Those familiar with the mission say they believe it can still happen — and that it's still worth doing.

"Do I have faith in NASA, JPL, all of those involved to be able to deliver on the Mars Sample Return mission with the attention and technical integrity that it requires? Absolutely," said Orlando Figueroa, chair of the the mission's independent review team and NASA's former "Mars Czar."

"It will require very difficult decisions and levels of commitment, including from Congress, NASA and the administration, [and] a recognition of the importance, just like was the case with James Webb, for what this mission means for space science."

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments