LA's long, troubled history with urban oil drilling is nearing an end after years of health concerns

Published in News & Features

Los Angeles had oil wells pumping in its neighborhoods when Hollywood was in its infancy, and thousands of active wells still dot the city.

These wells can emit toxic chemicals such as benzene and other irritants into the air, often just feet from homes, schools and parks. But now, after nearly a decade of community organizing and studies demonstrating the adverse health impacts on people living nearby, Los Angeles’ long history with urban drilling is nearing an end.

In a unanimous vote on Jan. 24, 2023, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to ban new oil and gas extraction and phase out existing operations. It followed a similar vote by the Los Angeles City Council a month earlier. The city set a 20-year phaseout period, while the county has yet to set a timetable.

As environmental health researchers, we study the impacts of oil drilling on surrounding communities. Our research shows that people living near these urban oil operations suffer higher rates of asthma than average, as well as wheezing, eye irritation and sore throats. In some cases, the impact on residents’ lungs is worse than living beside a highway or being exposed to secondhand smoke every day.

Over a century ago, the first industry to boom in Los Angeles was oil.

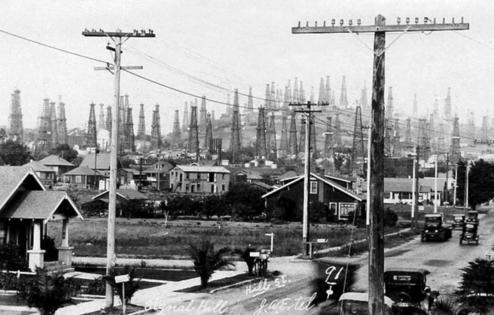

Oil was abundant and flowed close to the surface. In early 20th-century California, sparse laws governed mineral extraction, and rights to oil accrued to those who could pull it out of the ground first. This ushered in a period of rampant drilling, with wells and associated machinery crisscrossing the landscape. By the mid-1920s, Los Angeles was one of the largest oil-exporting regions in the world.

Oil rigs were so pervasive across the region that the Los Angeles Times described them in 1930 as “trees in a forest.” Working-class communities were initially supportive of the industry because it promised jobs but later pushed back as their neighborhoods witnessed explosions and oil spills, along with longer-term damage to land, water and human health.

Tensions over land use, extraction rights and subsequent drops in oil prices due to overproduction eventually resulted in curbs on drilling and a long-standing practice of oil companies’ voluntary “self-regulation,” such as noise-reduction technologies. The industry began touting these voluntary approaches to deflect governmental regulation.

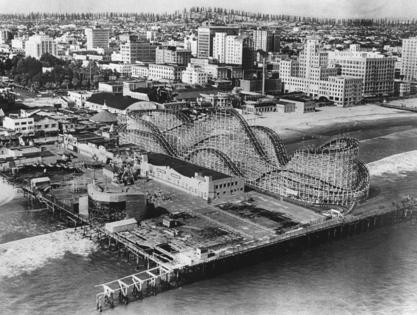

Increasingly, oil companies disguised their activities with approaches such as operating inside buildings, building tall walls and designing islands off Long Beach and other sites to blend in with the landscape. Oil drilling was hidden in plain sight.

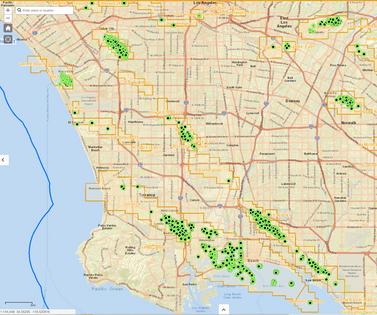

Today there are over 20,000 active, idle or abandoned wells spread across a county of 10 million people. About one-third of residents live less than a mile from an active well site, some right next door.

Since the 2000s, the advance of extractive technologies to access harder-to-reach deposits has led to a resurgence of oil extraction activities. As extraction in some neighborhoods has ramped up, people living in South Los Angeles and other neighborhoods in oil fields have noticed frequent odors, nosebleeds and headaches.

The city of Los Angeles has no buffers or setbacks between oil extraction and homes, and approximately 75% of active oil or gas wells are located within 500 meters (1,640 feet) of “sensitive land uses,” such as homes, schools, child care facilities, parks or senior residential facilities.

Despite over a century of oil drilling in Los Angeles, until recently there was limited research into the health impacts. Working with community health workers and community-based organizations helped us gauge the impact oil wells are having on residents, particularly on its historically Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

The first step was a door-to-door survey of 813 neighbors from 203 households near wells in Las Cienegas oil field, just south and west of downtown. We found that asthma was significantly more common among people living near South Los Angeles oil wells than among residents of Los Angeles County as a whole. Nearly half the people we spoke with, 45%, didn’t know oil wells were operating nearby, and 63% didn’t know how to contact local regulatory authorities to report odors or environmental hazards.

Next, we measured lung function of 747 long-term residents, ages 10 to 85, living near two drilling sites. Poor lung capacity, measured as the amount of air a person can exhale after taking a deep breath, and lung strength, how strongly the person can exhale, and are both predictors of health problems including respiratory disease, death from cardiovascular problems and early death in general.

We found that the closer someone lived to an active or recently idle well site, the poorer that person’s lung function, even after adjusting for such other risk factors as smoking, asthma and living near a freeway. This research demonstrates a significant relationship between living near oil wells and worsened lung health.

People living up to 1,000 meters (0.6 miles) downwind of a well site showed lower lung function on average than those living farther away and upwind. The effect on their lungs’ capacity and strength was similar to impacts of living near a freeway or, for women, being exposed to secondhand smoke.

We found evidence that oil-related contaminants, including toxic metals such as nickel and manganese, are getting into the bodies of the neighbors. This indicates contamination may be getting into the community.

Using a community monitoring network in South Los Angeles, we were able to distinguish oil-related pollution in neighborhoods near wells. We found short-term spikes of air pollutants and methane, a potent greenhouse gas, at monitors less than 500 meters, about one-third of a mile, from oil sites.

When oil production at a site stopped, we observed significant reductions in such toxins as benzene, toluene and n-hexane in the air in adjacent neighborhoods. These chemicals are known irritants, carcinogens and reproductive toxins. They are also associated with dizziness, headaches, fatigue, tremors and respiratory system irritation, including difficulty breathing and, at higher levels, impaired lung function.

Many of the dozens of active oil wells in South Los Angeles are in historically Black and Hispanic communities that have been marginalized for decades. These neighborhoods are already considered among the most highly polluted, with the most vulnerable residents in the state. Residents contend with multiple environmental and social stressors.

The city’s timeline for phasing out existing wells is set for 20 years, leaving concerns about continuing health effects during this period. We believe these neighborhoods need sustained attention to reduce the existing health effects, and the city needs a plan for a just transition and cleanup of the oil fields as the areas transition to new uses.

This updates an article originally published Feb. 3, 2022.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

How California’s ambitious new climate plan could help speed energy transformation around the world

Living near active oil and gas wells in California tied to low birth weight and smaller babies

Jill Johnston receives funding from the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences.

Bhavna Shamasunder receives funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the 11th Hour Project.

Comments