Russia has mobilized for war many times before – sometimes it unified the nation, other times it ended in disaster

Published in News & Features

Vladimir Putin’s mobilization of 300,000 additional Russian soldiers to fight in Ukraine has gotten off to a rocky start.

Nominally aimed at calling up reserve forces with prior combat experience, early reports suggest a broader dragnet and widespread resistance against the call-up. Recruitment offices have been torched, protests against the action have dotted Russian cities, and droves of men have reportedly fled the country to avoid being enlisted.

As a scholar of Russian history, I see this latest move by Putin in the context of past mass mobilizations undertaken by Russia throughout its history. Sometimes it has worked, bolstering a force while legitimizing conflict in the eyes of the public and instilling national unity. But it can also backfire, as the Russian president may find to his cost.

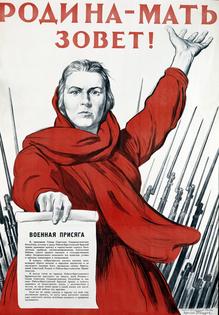

Putin most often uses World War II as his historical reference point. The Soviet Union suffered tremendous losses during the Nazi invasion but countered by conducting the most extensive mobilization that the world had ever seen and probably will ever see.

As well as mobilizing the entire economy for wartime production and putting women to work in factories in unprecedented numbers, the Soviet Union also mobilized 34 million soldiers, building one of the largest armies ever assembled. This total mobilization led Nazi Germany to suffer four-fifths of its total wartime casualties on the Soviet front and was the single most important reason Germany was defeated.

It also served to turn the fortunes of a Soviet state that had entered the war weakened by Josef Stalin’s campaign to force farmers into state-run collective farms, a deadly famine that resulted and waves of police repression that had killed millions of citizens.

Victory gave the Soviet Union a new legitimacy at home and abroad that helped it survive and even thrive as a great power for 45 more years. The powerful Red Army that was assembled swept through half of Europe and brought the Russian Empire’s borders further west than any tsar had done.

The success of this mobilization and the great Soviet victory have been central to Putin’s worldview. He decreed draconian penalties for any attempt to question Soviet conduct in World War II, like the brutal annexation of the Baltic states, mistakes by Stalin and his generals, or occupation policies in Eastern Europe. Putin also obsessed about Ukrainian nationalist partisans who fought against Stalin during the war, conflating them with contemporary Ukrainians who simply desire sovereignty.

Putin seems to have hoped to recreate the unifying, legitimizing results of the great World War II effort.

Indeed, mass mobilizations have periodically unified the nation at other times. In 1612, a mass rising led to a successful war to expel Catholic Polish invaders, ending a period of internal strife and leading to broad unity in favor of the new Romanov dynasty and its autocratic rule.

Two hundred years later, in 1812, Russia mobilized against a foreign invader, Napoleon, and won a decisive victory that brought Russian troops to Paris and made Russia a great power in Europe. It also ended Tsar Alexander I’s dalliance with liberal reforms. Russia became known as the “gendarme of Europe,” the active enforcer of an international alliance against constitutional liberalism.

But while these mobilizations for war unified the country and brought legitimacy to the regime, others did the opposite.

From 1768 to 1774, Catherine II, Russia’s greatest conqueror, launched a massive war against the Ottoman Empire that led to the conquest of much of modern southern Ukraine and Crimea.

But to win, Cossacks – irregular military groups living in Russia’s borderlands – and peasants bore the brunt. Formerly relatively free to choose the conditions of their service to the tsar, Cossacks were locked into the regular Russian army and sent to the front in large numbers. Peasants felt the twin burdens of ever tightening bonds of serfdom and wartime conscription.

The two groups joined together in a revolt that so seriously threatened the state that Catherine had to rush a peace settlement with the Ottoman Empire to bring the army home to crush the rebels.

In 1904, Russia underestimated the rising power of Japan and stumbled into a war with that country. A subsequent call-up of university students and young men for a very unpopular war proved to be a major cause of the revolution that ensued in 1905. Only when the tsar withdrew from the war and conceded a parliament and constitution was order restored.

Despite an effective mobilization of millions of soldiers at the beginning of World War I, Russia incurred massive losses as Germany and Austria-Hungary drove deep into Russian territory. Street protests against food shortages in February 1917 spurred a broad coalition of elected members of parliament and military commanders to overthrow the tsar. They thought a legitimate, popular government would inspire more fighting spirit among the troops.

The leaders of the new government doubled down on the war effort, ordering a major new mobilization of troops, calling up people who had been previously exempt, such as heads of households, older men and ethnic minorities. There were even orders to send to the front soldiers who had previously been kept in reserve garrisons because of suspect loyalties or subpar fighting qualities.

On paper, the Russian army swelled to 10 million men, the largest it had been through the entire war to date. With more troops and more weapons than the enemy and newfound legitimacy, the government overestimated popular support for the war and launched an offensive. But after a couple weeks of advances, the unreliable recent recruits were the first to desert, starting an avalanche of 2 million desertions that both destroyed the army and, as armed soldiers went back to their villages, started the agrarian revolution when peasants drove noble landlords out of the countryside and seized the land for themselves.

Fearing counterrevolution, the new government disbanded much of the police force but was unable to create a new one to replace it. The army was pinned down at the front and losing numbers fast as soldiers went home to claim land. It could not protect the state from the small Bolshevik faction of the communist movement, which conducted a successful armed coup in October 1917. The summer offensive has gone down in history as one of the worst military gambles ever.

Putin appears to look toward World War II, missing the lessons of the earlier Great War.

The mobilization to fight World War I drew support from national representatives and from a relatively free press. While the population was weary of war by 1917, few questioned the legitimate need to defend the country against the German invaders.

Putin’s war in Ukraine is very different. It is widely seen as unnecessary, public support is tepid, and there is no free press or freely elected representatives to give it legitimate support.

The mobilization of 1917 provides a stark lesson that larger armies are not necessarily stronger ones, and adding large numbers of unreliable soldiers to an army can be an enormous gamble.

The usually cautious military observer Michael Kaufman responded to Putin’s mobilization by declaring that Putin now has staked his regime on the outcome of the war. It is already clear that this war will not be a unifying, legitimizing event like World War II. But it remains to be seen whether this mobilization will go down the 1917 road to military dysfunction and revolution.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Eric Lohr, American University. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more:

Famine, subjugation and nuclear fallout: How Soviet experience helped sow resentment among Ukrainians toward Russia

A historian corrects misunderstandings about Ukrainian and Russian history

Eric Lohr has received funding from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research Fellowship (2012) and the Kennan Institute for Russian studies fellowship (2005). He has served as director of American University's Carmel Institute for Russian History and Culture (2011-12; 2019-20), an organization that provided scholarships for students to study Russian language and previously included film screenings and cultural events at the Russian Embassy. This past activity in no way influences his scholarship or political views.

Comments