Plunging pound and crumbling confidence: How the new UK government stumbled into a political and financial crisis of its own making

Published in Business News

In other words, investors were already predisposed to view the long-term trajectory of the U.K. economy and the British pound in a negative light.

Truss, who became prime minister on Sept. 6, 2022, also didn’t have a strong start politically.

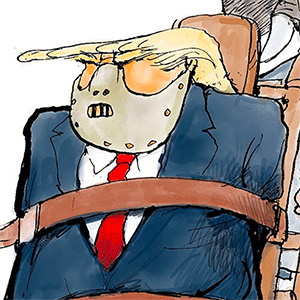

The government of Boris Johnson lost the confidence of his party and the electorate after a series of scandals, including accusations he mishandled sexual abuse allegations and revelations about parties being held in government offices while the country was in lockdown.

Truss was not the preferred candidate of lawmakers in her own Conservative Party, who had the task of submitting two choices for the wider party membership to vote on. The rest of the party – dues-paying members of the general public – chose Truss. The lack of support from Conservative members of Parliament meant she wasn’t in a position of strength coming into the job.

Nonetheless, the new cabinet had an ambitious agenda of cutting taxes and deregulating energy and business.

Some of the decisions, laid out in the mini-budget, were expected, such as subsidies limiting higher energy prices, reversing an increase in social security taxes and a planned increase in the corporate tax rate.

But others, notably a plan to abolish the 45% tax rate on incomes over £150,000, were not anticipated by markets. Since there were no explicit spending cuts cited, funding for the £161 billion package was expected to come from selling more debt. There was also the threat that this would be paid for, in part, by lower welfare payments at a time when poorer Britons are suffering from the soaring cost of living. The fear of welfare cuts is putting more pressure on the Truss government.

Even as the new U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng was presenting the mini-budget on Sept. 23, the British pound was already getting hammered. It sank from $1.13 the day before the proposal to as low as $1.03 in intraday trading on Sept. 26. Yields on 10-year government bonds, known as gilts, jumped from about 3.5% to 4.5% – the highest level since 2008 – in the same period.

The jump in rates prompted mortgage lenders to suspend deals with new customers, eventually offering them again at significantly higher borrowing costs. There were fears that this would lead to a crash in the housing market.

In addition, the drop in gilt prices led to a crisis in pension funds, putting them at risk of insolvency.

...continued

Comments