Andreas Kluth: Don't buy the MAGA meme about weak Biden

Published in Op Eds

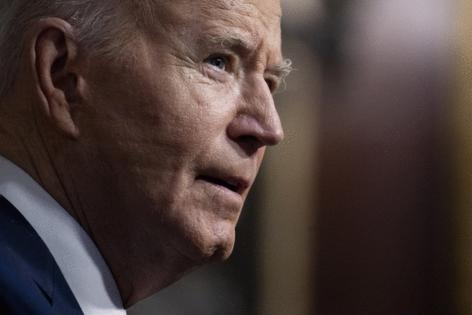

The umpteenth reason why I dread this election season is that former president Donald Trump and his campaign have already chosen to go infantile and primitive in matters of foreign policy and national security. The meme MAGA is pushing — on all channels, in answer to all questions, all the time — is that President Joe Biden is “weak,” while Trump is self-evidently “strong.”

Trump deploys “weak” as one of the default adjectives in almost every barrage he fires at his opponent. His support network then provides the heavy artillery. “JOE BIDEN IS WEAK,” screams the Republican National Committee, splicing clips of Biden saying “Don’t” to the Iranian mullahs and their proxies, which is meant to suggest that this man in the White House, unlike you-know-who, doesn’t know how to deter bad guys.

The meme’s underlying theory is as cynical as it is apt. It’s based on the “illusory truth effect,” the empirically proven phenomenon that anything — truth, half-truth or lie — is perceived as valid when repeated often enough. People who watch Fox News, say, keep hearing that everyone else is worried about Biden’s weakness, so they start believing they should worry about it too. The result is that Biden comes across as “likable” but Trump as “strong.”

No doubt the Trump campaign also keeps mentioning weakness to amplify perceptions of the president’s physical frailty. It’s yet another way of setting up Trump as the foil: The Donald admires strongmen and poses as one to his fan base. And there’s a reason the term is “strongman,” not strongperson (which may be one reason why HBO’s “The Regime,” a series about a central European autocrat played by Kate Winslet, isn’t all that convincing). Among primates, alpha dominance has always been linked to virility; as 1 Kings 1 discreetly puts it, King David knew it was time to go when “he gat no heat.”

If that’s the cynical and subliminal background to the weakness campaign, it’s all the more facile because it omits contemplating what weakness and strength even mean in world politics. Yes, strength does require power and the readiness to use it. In that sense Biden, like Trump as president, has plenty, because America’s economic and military prowess remain unrivaled. But there’s so much more to it.

The question relevant for leadership is how to use power, both the hard and the soft kind: whether to harness it in pursuit of values and interests or merely to brandish it in fits of narcissism. Trump’s style fits the latter description, thinks Kori Schake, a Republican foreign-policy expert who served on the National Security Council under George W. Bush and later worked for the campaign of John McCain. The Donald is a “chicken hawk,” she told me.

History is replete with tragic analogs to Trump, but the one I find most pertinent is Wilhelm II, the last Kaiser of Imperial Germany. The Hohenzollern monarch had a withered left arm and a bundle of hang-ups, and spent his life trying to compensate with martial displays, often changing military uniforms several times a day. Afraid of looking weak, he cosplayed bellicosity to seem strong, which was one big reason why Europe in 1914 “sleepwalked” into World War I and lost an entire generation.

Biden’s foreign policy, admittedly, is also a mixed bag of hits and misses. Exhibit A for his alleged weakness is the botched American pullout from Afghanistan in 2021. That was chaotic and incompetent. But the strategic decision to redeploy American might elsewhere was right. Biden understood that he had to conserve American power to stop Russian aggression in Europe and contain Chinese revanchism in Asia.

Paradoxically, Biden has also been looking weak vis-a-vis not one of America’s foes but one of its friends: Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu. For six months, the president has tried to moderate the prime minister — in order to destroy Hamas and free the hostages while also minimizing civilian deaths and misery and preventing escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict into a wider regional war. “Bibi,” in turn, keeps snubbing Biden.

Toward America’s adversaries, however, Biden has been simultaneously decisive and measured, which is to say effective. When Vladimir Putin failed to subjugate Ukraine quickly in 2022, the Russian president threatened, and probably contemplated, the use of nuclear weapons. Biden deterred him, by working discreetly with other powers, including China, while also signaling that he would punish Russian forces with a devastating conventional (as opposed to nuclear) counterstrike.

After Iranian proxies killed three American service members stationed in Jordan, Biden used enough force to signal to Tehran that it and its proxies must stop targeting US assets and citizens; so far Iran seems to have got the message. After Israel opened the latest round of escalation by striking an Iranian diplomatic compound in Syria, Biden helped Israel defend itself against the Iranian retaliation, then talked Bibi into a counterstrike limited enough for Tehran to call it a day.

What this statecraft suggests is not weakness, but a mature kind of strength — the sort that doesn’t have to prove itself. Biden understands not only his own strengths and weaknesses but also those of enemies such as Putin and the mullahs. Through these nuances, he steers the US and the world as best he can away from cataclysm and toward order.

This is the kind of strength that Herodotus would recognize, based on intellectual humility, not hubris or posturing. It is the fortitude that makes a leader choose advisers who speak truth to power, not toadies who pledge unconditional loyalty. As Bill Clinton said after his time in the White House, “strength and wisdom are not opposing values.” Trump may or may not have the first, but surely lacks the second; Biden can plausibly stake a claim to both.

____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments