Politics

/ArcaMax

Commentary: The Democratic Party's backward induction problem in the presidential race

In game theory, games among strategic players that continue over time can often be solved by “backward induction”: Look at the outcome at the last stage of the game to figure out whether the players will end the game before it gets there.

As it stands, by backward induction, Vice President Kamala Harris will be the presidential nominee of ...Read more

Joe Battenfeld: Democrats and complicit media circle wagons around Kamala Harris

Democrats and a complicit media are already building a cult of personality around Kamala Harris, circling the wagons to protect her from expected Republican attacks.

Whether it’s planting memes on the Internet or stories in the media, the Harris campaign is riding a wave of favorable publicity, painting the vice president as a hip and likable...Read more

Commentary: At the Olympics, must it be men versus women?

It may come as no surprise that the first modern Olympics were a men-only affair. The second, in Paris in 1900, included 22 women, and from then on, every Olympic Games has wrestled with whether, and how, to treat men and women differently. The concepts of equality and fairness are murky at the point where sports meets gender, and Olympic ...Read more

Editorial: The Veep and the border -- Kamala Harris' role was never 'border czar'

Among the attacks the Donald Trump camp is lobbing at presumptive Democratic nominee Kamala Harris is the notion that the vice president failed at her one crucial job in the White House, that of “border czar.” In truth, this was never her role; among other things in her portfolio was helping address the “root causes” of migration from ...Read more

Editorial: A hopeful step for Parkinson's patients

It began with a teacup and saucer at a work event. It was 2010, and Sherrie Pugh picked up the offending objects, but, before she could get coffee, the uncontrollable rattling prompted a helpful staffer to intervene. A function Pugh thought she'd have for life, that of pouring coffee: gone. It would take five years of tremors, and countless ...Read more

Mark Gongloff: Global heating is no longer a tomorrow problem. It's today's

For decades, global warming was widely seen as a tomorrow problem, something for our hapless grandchildren to worry about. But with heat records tumbling relentlessly, it’s becoming clear that tomorrow has basically arrived. We are the hapless grandchildren. And it’s also becoming clear that we’re not ready for the heat.

Monday was the ...Read more

Commentary: Public school gender activists are pushing Michigan parents out

When it comes to matters of sex and gender identity, the parents of students in Michigan public schools might think their opinion comes first. They would be wrong. The gender activists are in charge, with parents not only denied a role in decisions about such important matters, but increasingly kept in the dark altogether.

And it’s about to ...Read more

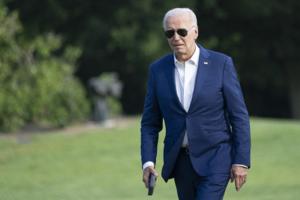

Francis Wilkinson: Biden's graceful exit shows how a healthy party should work

President Joe Biden delivered his after-action report to the nation tonight. His conclusion: Mission accomplished.

In an Oval Office address that was often moving, and mindful of this season’s democratic peril, Biden unfurled a litany of achievements. But he made it clear that in the wake of departing the Democratic ticket he intends to ...Read more

Editorial: NATO needs better bridges -- and bulwarks

Although the U.S. and its allies agreed recently to put Ukraine on an “irreversible path” to NATO membership, there’s no avoiding the obvious: A Trump presidency could well render such pledges meaningless.

Former President Donald Trump has threatened to hollow out U.S. support for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization — even if ...Read more

Commentary: How Trump and Vance betray America's workers

It was a scene to behold: a union president delivering a booming, barn-burner speech at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee — “the first Teamster in our 121-year history” to address the Republican Party, Teamsters President Sean O’Brien told the cheering crowd.

While the union hasn’t endorsed former President Donald Trump...Read more

Editorial: Don't be fooled by Trump's and Republicans' abortion myths

Abortion opponents peddle various myths about the procedure to discredit it and demonize the people who provide or support it. Abortion is healthcare. The earlier it is available, the easier it is for people to make choices about their bodies that will affect the rest of their lives. But during election season, expect to hear some or all of ...Read more

Commentary: The Olympics promise to be socially responsible. How's that working out?

Olympic host cities make promises that are all but impossible to keep, and in recent years, the organizers’ wishful thinking about housing and neighborhood redevelopment has been one of the cruelest Olympic disappointments.

As the 2024 Paris Games approach, we are seeing it all over again — displacement, gentrification and the unhoused “...Read more

David Fickling: Olympics host cities don't belong on a warming planet

What’s the biggest event at the Olympic Games?

There’s a good case that it’s not running, or swimming, or gymnastics, but the celebration of nationhood. The opening ceremony to the 2008 Beijing Games was the most-watched event in television history. In the U.S. alone, tens of millions routinely tune in to the first night’s display. This...Read more

Editorial: Trump and oil companies are lying to you about electric cars to serve their own interests

Oil companies are worried that federal incentives and the growing popularity of electric vehicles will eat into their profits and threaten their stranglehold over energy consumption. Former President Donald Trump and other Republican politicians want to exploit consumer and autoworker anxieties about the transition to zero-emission vehicles to ...Read more

Editorial: Falling on her sword -- Secret Service Director Kimberly Cheatle failed and had to resign

Secret Service Director Kimberly Cheatle should have saved herself from being roasted for 4 hours and 40 minutes Monday by justifiably angry members of the House Oversight Committee livid over the failures of the Secret Service to prevent the shooting of Donald Trump at a Pennsylvania rally 11 days ago. She should have resigned rather than sit ...Read more

Ryan J. Rusak: A messaging mess for Democrats -- 3 dumb arguments so far about Trump, Harris, Biden

Two days into the reshaped presidential race, we have a sense of Democrats’ initial attempts to define the race between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. The messaging is not impressive.

Three prominent arguments so far are a stretch at best and downright fantasy at worst. Let’s take a look.

Biden is a great president and patriotic hero

...Read more

Patricia Lopez: For once, it's Democrats who fall in line

Democrats are coming together with a swift, unified show of force that seemed unfathomable just days ago. It has made a mockery of a still-new Republican talking point — that President Joe Biden’s departure would leave Democrats divided and in disarray.

To Republicans’ dismay, Democrats are instead falling into line like, well, the GOP ...Read more

COUNTERPOINT: Bad policies, not gender, will cost Kamala Harris the presidency

Now that Vice President Harris is heir-apparent for the Democratic presidential nomination (chosen by party elites without a democratic process from her party’s voters), the next step we’ll see from the left is whipping out the women’s card.

We’ve seen this in numerous other races, including with former presidential candidate Hillary ...Read more

Commentary: Why Harris should pick former astronaut Mark Kelly as running mate

With the Democratic presidential nomination all but delivered for Kamala Harris, speculation has turned to who would best compliment her as the vice-presidential nominee. There are certainly several interesting possibilities but there is one who, like Harris herself, draws stark and strategic contrasts with the Trump-Vance ticket: Sen. Mark ...Read more

POINT: Why gender matters in politics, and what has to change

Gender shouldn’t matter when choosing a president — but after nearly 250 years of American democracy and zero women presidents, it clearly has. Now, if we want to save democracy, something has to change.

The question isn’t whether voters are ready for a woman leader. Vice President Harris has already passed that milestone.

She has more...Read more