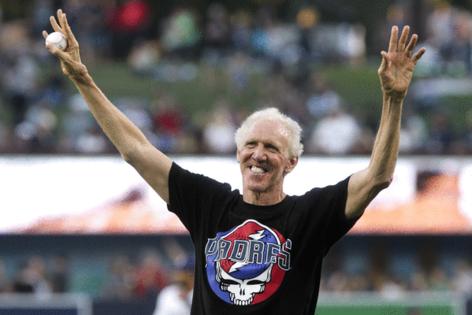

Appreciation: Bill Walton was a passionate music fan who saw the Grateful Dead more than 850 times

Published in Entertainment News

SAN DIEGO — Bill Walton's passion for basketball was rivaled only by his passion for rock 'n' roll, in particular the music of the Grateful Dead. The San Diego-bred basketball icon — who died Monday at the age of 71 following a battle with cancer — saw the Dead perform more than 850 times, starting with a 1967 Mother's Day show at San Diego State University's Aztec Bowl.

"I loved the Dead right away, the first time I heard them," Walton told this writer in a 1992 Union-Tribune interview. "I loved the speed, the dancing, the rhythm, the creativity. It's just like being on a basketball team. Basketball, like good, creative, rock music, is never the same."

A frequent attendee at concerts in San Diego — including Neil Young & Crazy Horse's April 26 performance at SDSU — Walton was also a devoted fan of everyone from Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones to Bonnie Raitt and the Beach Boys.

When he was negotiating his contract with the San Diego Clippers in 1979, Walton sought a clause from the team that guaranteed him 56 tickets to a Bruce Springsteen concert. His quest was successful.

But it was the Dead's music that most enchanted him throughout his life.

In recent decades Walton sat in as often as his schedule allowed with the Electric Waste Band, a leading Dead tribute band, at its weekly performances at Winstons in Ocean Beach.

Elvis Costello, who was also a major Deadhead, invited Walton to duet with him on the song of his choice at Costello's 2012 show at Humphreys Concerts by the Bay. Walton chose the Dead's 1971 classic, "Ramble On Rose," and enthusiastically sang along on the chorus with Costello.

"There's never a day in my life where I don't listen to the Grateful Dead," Walton said in a 2015 Union-Tribune interview.

"And when I don't listen, it's because I'm sick and because I'm not smart enough to turn the music on! But (I always welcome) the ability to consume, and the ability to immerse yourself, in the music culture and in the art work, the history and the inspiration, and the light and all the things that make the Grateful Dead what they are. Because they have been at the forefront of everything good in the world, in terms of driving us to a better place."

Musical bliss

Walton was friends with the members of the Dead, who would sometimes stay at his Balboa Park-area home. Its interior, which looked like a Grateful Dead shrine, included a drum set given to him by the band that was mounted horizontally on a living room wall.

The Dead's former drummer, Bill Kreutzmann, fondly referred to Walton as "Celebrity Deadhead Number One." When the Dead performed in front of the Great Pyramid in Egypt in 1977, Walton was in the audience. In 2015, he co-hosted the livestreams of the band's five farewell stadium concerts.

"I met Bill for the first time at a Dead show in Ventura, around 1984," longtime Dead spokesman Dennis McNally told the Union-Tribune in 2015. "People knew he was a Deadhead, and there was a certain pride in him being a celebrity and a Deadhead. We liked to brag about the famous Deadheads.

"His parents must have been the most loving, remarkably wonderful parents ever because Bill has a quality of enjoyment of life, a sweetness of disposition and an unwavering enthusiasm that are all absolutely extraordinary. He will do anything for his friends. He spent a certain amount of time backstage (with the Dead), because he was the band's friend, and everybody's friend. But he was always there to see the show, not to have special privileges."

Walton beamed during his 1992 Union-Tribune interview when asked to recount his earliest experiences in basketball and music.

"Almost from the very beginning, basketball came easy to me," he said. "But only in the sense that I liked it so much that it never seemed like work. To me it was never a drag to go out in the backyard and just shoot hoops, or to go down to the playground and find some guys and organize a game. I looked forward to that each and every day.

"But I was raised in a very musically oriented family. My father loved music, especially classical music, and I actually played some instruments as a child. I played baritone sax, my brother Bruce played the trombone, my brother Andy played saxophone, my sister Cathy played the flute, and my dad played the piano. We played together a bunch at home, but I don't know if you'd quite call them 'concerts.'"

Yet, while his librarian mother and music teacher father encouraged their children to appreciate many art forms, rock music was not one of them.

"My parents wouldn't let me play rock 'n' roll on the family stereo," Walton recalled. "So, from the time I was in high school and got my own stereo, I'd always have rock music on, just to get the rhythm going. It was the rhythm and the thought and the surge, the charge of: 'Let's go! Let's go get it done!'

"I'd always played music before the games; I'd come walking out of my room ready to go, and I did that my entire basketball career. I've listened to so much music now that the songs just go constantly in my head. And I love concerts. The excitement of the concerts is just like the excitement of the big games, you know, the anticipation of the crowd."

'We met at church'

Walton met his second wife, Lori Matsuoka, at a 1990 Dead concert. They married a year later and were often seen together at concerts in San Diego.

"Our versions of how we met are really different," Lori Walton told the Union-Tribune in 2015. "This is mine: 'We met backstage at a Dead concert.' Bill's version is: 'We met at church.' But I think it's because he considers the Dead concerts to be church! My mom read once that we met at church. She phoned me to say she was so happy I'd met Bill at church. I didn't have the heart to tell her the truth."

Walton's 1992 basketball audio memoir, "Men Are Made in the Paint," featured endorsements on its cover from both former Boston Celtics' teammate Kevin McHale and Dead drummer Mickey Hart. It also included musical interludes by former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who — like Walton — was a UCLA alum.

"Basketball and music are so very similar," Walton told the Union-Tribune in 1992. "The thing that's different with music is that you don't really have an opponent; you don't have someone who's trying to frustrate you.

"In music, everybody's trying to encourage you all the time. In sports, there's always a whole side that's trying to keep you from doing what you want to do, which I really like. I like that confrontational relationship between the fans and the players. I think that's good."

I first interviewed Walton at his home in 1992 and he was warm and welcoming. At some point during our extended conversation, he asked me when I had first seen the Dead perform. I told him it was as a 10th grader in 1972 at the band's concert in Frankfurt, Germany, which was prominently featured on the Dead's classic triple-album, "Live Europe '72."

Walton was impressed — it may well have been one of the few standout Dead concerts anywhere he did not actually attend himself. But he was incredulous when I told him I had to leave early during the third hour of the show.

"You left? You left!" he sputtered. "What could you have possibly had to do that was more important?"

I explained that the venue was about 10 miles outside of Frankfurt, and that — unless I wanted to walk home — I had to leave to catch the last bus. This was a totally unacceptable answer for Walton, who had befriended the Dead in the mid-1970s during his time playing for the Portland Trailblazers.

As it transpired, Walton could have met the Dead during his tenure at UCLA. But he declined.

"I'm a lifelong stutterer," Walton told me, "and learning how to speak (well) is my greatest accomplishment. My limitations with speech and communication had been one of the most difficult and painful hurdles, mountains, for me to overcome. I was so shy, and it was so hard to talk ...

"I got national publicity playing (basketball) for UCLA, and people had come up to me, constantly, and said: 'Bill, come meet the band.' And I always said: 'No.' I was too shy. Anyhow, in Portland, as the band played, they kept looking out, and thinking: 'Something is wrong. Why is everyone sitting down, and that big guy with red hair is standing?'

"Then they realized: 'Oh, they are all standing, and he is, too.' So they had someone from their (road) crew come to me, and he said: 'Why don't you come and watch from backstage, so everybody else can see?'"

Walton grinned as he recounted the story.

"I said: 'Come on! This is where I want to be!'" he continued. "I liked being up close and in front of the stage, watching the Dead and their light show, and being in the crowd ... So, I turned them down in Portland, when they invited me to watch from the stage. But I said: 'I'll come back at intermission.' I met everybody in the band, and things were never the same again. They became our best friends and part of our lives. My life has been incredibly enhanced by my friendship and relationship with the Dead."

Through the decades, the 6-foot-11 Walton was a frequent presence at various San Diego concert venues, be it a Bob Dylan gig at UCSD's RIMAC Arena, an Elvis Costello solo performance at the Balboa Theater or a Paul McCartney show at Petco Park, where Walton — seated directly in front of a man in a wheelchair — joyously danced throughout

Walton often would bring a padded chair to concerts, the better to accommodate his large frame and sensitive back — he had undergone a spinal fusion in 2009. He was a frequent presence at Humphreys Concerts by the Bay, where he and his wife, Lori, averaged at least 10 performances each year.

Fellow concertgoers lit up when Walton was in their midst. I can't recall a single time when he did not return their smiles as he interacted with them. Walton seemed to feed off their enthusiasm as much as they did his. And if they were Dead fans, as many were, the bond with Walton was instantaneous.

Or, as he so often liked to say: "Everyone's a Deadhead!"

Walton's enthusiasm for the Dead was almost matched by his disdain for former President Richard M. Nixon, who — as recently as a few years ago — Walton still publicly referred to as "the evil prince of darkness." Walton, who had protested against the war in Vietnam, was arrested during an anti-war demonstration that blocked traffic on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles.

Music was an endless source of inspiration for Walton, whose face would glow when he discussed a favorite song, album or concert. He was near-encyclopedic in his knowledge of the music of the Dead and Dylan, who toured and made an album together in the late 1980s.

During a pre-concert chat prior to Dylan taking the stage at his 2008 performance on the Qualcomm Stadium practice field in Mission Valley, Lori Walton told my wife and me about one of her first dates with her legendary husband-to-be.

Dylan was playing seven consecutive concerts at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles," Lori recalled, and Bill took her to all seven. It was a kind of musical trial by fire and she passed, with flying colors. So did he.

Or, as Bill Walton told me in 2015: "We went to every single one. When she was still there at the end of that run of Dylan concerts, I knew I had a chance!"

©2024 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments