Boeing says no 787 safety risk after whistleblower raises troubling claims

Published in Business News

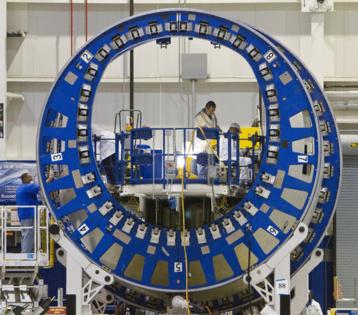

NORTH CHARLESTON, South Carolina — At its 787 Dreamliner manufacturing complex in South Carolina on Monday, Boeing detailed an immense amount of analysis and testing it has done since the discovery in 2020 of small gaps at the fuselage joins on the jet.

Boeing has made meticulous, time-consuming changes to the way it manufactures the 787’s carbon composite airframe to eliminate the gaps. It must do so to meet the specification.

More importantly, Boeing insists that extensive testing overseen by the Federal Aviation Administration and inspections of the current in-service fleet shows definitively that the gaps, which exist in nearly 1,000 Dreamliners flying today, pose zero safety risk.

“We haven’t identified any safety issues,” said Steve Chisholm, chief engineer for Boeing Mechanical and Structural Engineering. “We have not seen anything in service related to [the gaps] that would indicate that there is an issue with the in-service fleet.”

In a press briefing and tour of the 787 fabrication and final assembly facility in North Charleston, S.C., Boeing scrambled to respond to damaging allegations last week by Sam Salehpour— an Everett engineer who worked on the 787 and 777 programs, now a public whistleblower — that it has not eliminated the gaps and that they pose a risk of “catastrophic failure.”

Salehpour’s allegations come as Boeing continues to face fallout from a Jan. 5 midair blowout that saw a panel pop out of a 737 MAX 9. That incident prompted ongoing inquiries into the 737 program and raised fresh questions about Boeing’s broader safety culture.

In response to Salehpour’s claims, Boeing described its testing and manufacturing changes to journalists during a visit to its North Charleston facility.

Engineers smashed 300-pound spheres swinging on a pendulum into a fuselage section to deliberately damage it, causing one of the stiffening rods to break. They then applied loads 15% greater than those typical in flight and repeated this 40,000 times. It found “there was no growth in the damage,” Chisholm said.

He contrasted this with what happens on a metal airframe, such as the 737 or the 747. If a crack develops in the thin metal skin, it can propagate and tear through the structure as if it were unzipping.

While metal fatigue might result in such cracks, Chisholm said damage to a composite material would take the form of delamination, when the plies of carbon fiber separate.

...continued

©2024 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments