The 8-hour workday was the paramount goal of unions in the 1800s. Is the 4-day workweek next?

Published in Business News

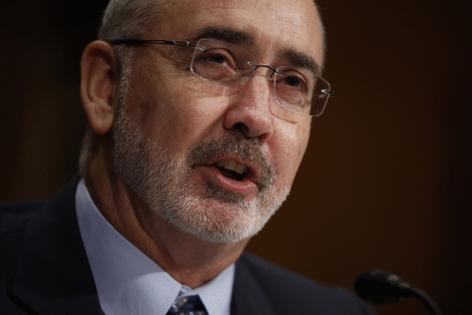

G. Roger King, a lawyer with the lobbying organization for big corporate human resources officers, assured the members of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that he and his colleagues were fully on board with the concept of a four-day work week.

His HR colleagues, he told the senators at a March 14 hearing, are "not opposed to 32-hour work weeks or other nontraditional work week configurations" ... in principle.

Unfortunately, he said, a four-day week would only exacerbate existing labor shortages, would be a "backdoor" increase in the minimum wage, and in any case should be driven by "traditional market forces," not mandated by federal law.

Are you surprised that big employers would fight a shorter work week for their employees? Me neither.

"As a general rule," says labor historian Erik Loomis of the University of Rhode Island, "employers are opposed to every labor reform. They always say it's going to be a disaster for the economy, and it never is."

That's been true of every increase in the minimum wage, and it was true of the last government-mandated contraction of the workweek — the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established the minimum wage, banned child labor in factories and mandated an eight-hour workday and 40-hour workweek, after which rank-and-file workers are entitled to time-and-a-half pay.

The workweek is now back on the front burner, in part because unions are feeling their oats lately, and also because Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vermont, the HELP Committee chairman, has introduced a bill to mandate a 32-hour workweek with no loss of pay for those transitioning from the traditional 40 hours.

"As a result of the extraordinary technological transformations that we have seen in recent years, American workers are now over 400% more productive than they were in the 1940s," Sanders said in opening the hearing. "Almost all of the economic gains of that technological transformation have gone straight to the top, while wages for workers have remained stagnant, or even worse."

He's right. Rank-and-file worker wages have barely kept up with inflation, while CEO pay has rocketed into the stratosphere. In 1965, the average chief executive's pay at the 350 largest U.S. companies was about 20 times the average wage of their rank-and-file workers, according to the labor-affiliated Economic Policy Institute. In 2022, it was 344.5 times as much.

What paid for that run-up in executive pay was a massive increase in U.S. worker productivity. But as Sanders observed, the average worker received barely a taste of the gains.

...continued

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments