Yes, we're polarized, but how do we get un-polarized?

First of all, thank you for reading.

I know you have a lot of choices to chew up your time, so I appreciate you spending some of it with me.

I'm being extra nice because I've been reading the much-talked-about book "Why We're Polarized," by journalist Ezra Klein, the founder of Vox, host of a popular podcast and passionately devoted analyst of political science studies.

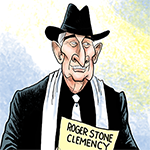

The importance of the political polarization topic has been increasingly obvious as we've headed into election years like this one. You could hear it from Democrats on Friday, frustrated after Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee declined to cast one of the four votes Democrats needed from Republicans to call for witnesses in the Senate impeachment trial of President Donald Trump.

Perhaps inevitably, one of the culprits singled out by Klein as a factor in our deeply divided state is the news media. As I often have observed, no one criticizes media more than those of us who work in the profession, and Klein has noticed the obvious: In the rush for eyeballs, profit-driven media are behaving as competitively as television news always has.

And as Klein reminds us, we've had an explosion of news media choices, more than any normal human could keep up with.

Think back. Between 1995 and 2005, our choices expanded greatly. In 1995, we had our hometown papers, a few radio stations, the three nightly network newscasts, the 15-year-old CNN and a few news magazines.

A decade later, we had access via our favorite web browser to almost any newspaper or magazine in the world, Fox News and MSNBC in the cable news race as well as satellite radio, podcasts, blogs and -- well, you get the idea.

But working along with the media influence are other polarizing factors, particularly one that a lot of people are not always comfortable talking about. "A core argument of this book," he writes, "is that everyone engaged in American politics is engaged in identity politics."

Not that there is anything wrong with that, Klein hastens to add. "This is not an insult, and it's not controversial. ... Identity is present in politics in the way gravity, evolution or cognition is present in politics ... because it is omnipresent in us."

Unfortunately, the term "identity politics" has been weaponized to a degree that it is almost impossible to use it to engage others without having to explain how your identity shapes you and that engagement.

Part of the confusion stems from the use of the term to demonize marginalized groups that are organizing in their own interests. That includes not only controversial, loosely organized movements such as Black Lives Matter but also more mainstream campaigns for pay equity for women and people of color.

And tribal politics, let us not forget, are not limited to one party. When we saw working-class white men and married white women turn from voting for Democrat Barack Obama in the 2008 and 2012 elections to Republican Donald Trump in 2016, not many people referred to Trump's appeal as "tribal politics." But the proper use of that term helps us understand why the switch was made and whether those voters might ever switch back.

To me, the polarization of America's party politics explains the shift of African American voters from the Republican to Democratic parties. Close to 40 percent of black voters -- including my parents -- voted for the Republican candidate and war hero Dwight Eisenhower in the 1950s. The realignment we see today began in 1964 after the Republican "Party of Lincoln" nominated Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, who had voted against the Civil Rights Act that year.

It's hard to believe that, as Klein points out, the American Political Science Association in the 1950s complained that the two parties weren't more polarized, so voters would have more ideological choices.

Other factors cited by Klein include campaign finance laws that, ironically, made the parties weaker as candidates found alternative funding sources. The growth of independent fundraising, including donations from outside of one's state, encouraged more extremes as big money donors promoted more extreme positions.

Unfortunately, Klein does a lot more explaining of our problems than offering of solutions, but changing our "framework for understanding" is closer to his purpose, he says. That's OK. We need some strategic road maps and moral compasses to understand one another in these rapidly changing times.

We can begin, for example, with reintroducing ourselves to each other and doing a better job of listening across party and tribal lines. We have the technology and the anger to bring a lot of heat to politics. We also need to try to bring some light.

========

(E-mail Clarence Page at cpage@chicagotribune.com.)

(c) 2020 CLARENCE PAGE DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE MEDIA SERVICES, INC.