Peaches are a minor part of Georgia's economy, but they're central to its mythology

Published in Science & Technology News

The 2023 Georgia peach harvest is looking bad, although the details are sketchy. By some accounts, it’s the worst since 1955. Or maybe since 2017. There are estimates that a mild winter and late spring frost have cost Georgia growers 50% of their crop. Or perhaps 60%, or 85% to 95%. Consumers, say the growers, should expect less fruit, though what’s produced may be “fantastic and huge and sweet.” And they should expect to pay quite a bit more.

As ominous as this may sound, the unpredictability of Georgia’s peach harvest has been predictable since the industry’s earliest days. So has public hand-wringing about it. It can be hard to say what a “normal” year is. In 1909, growers produced just over 826,000 bushels. In 1919, it was up to 3.5 million, then 4.4 million in 1924, then back down to 1 million in 1929.

There may be plenty of peaches on Georgia license plates, but according to the University of Georgia’s 2021 Georgia Farm Gate Value Report, the state makes more money from pine straw, blueberries and deer-hunting leases. It has 1.21 million acres planted with cotton, compared with 11,582 acres of peach orchards. Georgia’s annual production of broiler chickens is worth almost 50 times as much as its peaches.

Why do Georgia peaches loom so large when they account for only 0.58% of the state’s agricultural economy, and Georgia produces only between 3% and 5% of the U.S. peach crop? The answer is that the Georgia peach is a cultural icon as well as an agricultural commodity. As I have documented, its story tells us much about the relationship between environmental uncertainty and commercial agriculture.

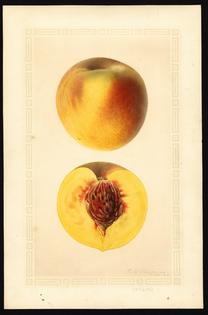

Peaches (Prunus persica) were introduced to North America by Spanish monks around St. Augustine, Florida, in the mid-1500s. By 1607 they were widespread around Jamestown, Virginia. The trees grow readily from seed, and peach pits are easy to preserve and transport.

Observing that peaches in the Carolinas germinated easily and fruited heavily, English explorer and naturalist John Lawson wrote in 1700 that “they make our Land a Wilderness of Peach-Trees.” Even today, feral Prunus persica is surprisingly common, appearing along roadsides and fence rows, in suburban backyards and old fields throughout the Southeast and beyond.

Yet for such a hardy fruit, the commercial crop can seem remarkably fragile. This year’s heavy loss is unusual, but public concern about the crop is an annual ritual. It begins in February and March, when the trees start blooming and are at significant risk if temperatures drop below freezing. Larger orchards heat trees with smudge pots, or use helicopters and wind machines to stir up the air on particularly frigid nights.

The Southern environment can seem unfriendly to the fruit in other ways, too. In the 1890s many smaller growers struggled to afford expensive and elaborate controls to combat pests such as San Jose scale and plum curculio.

In the early 1900s, large quantities of fruit were condemned and discarded when market inspectors found entire car lots infected with brown rot, a fungal disease that can devastate stone fruit crops. In the 1960s, the commercial peach industry in Georgia and South Carolina nearly ground to a halt because of a syndrome known as peach tree short life, which caused trees to suddenly wither and die in their first year or two of bearing fruit.

In short, growing Prunus persica is easy. But producing large, unblemished fruit that can be shipped thousands of miles away, and doing so reliably, year after year, demands an intimate environmental knowledge that has developed slowly over the past century and a half of commercial peach production.

...continued

Comments