Farmers face a soaring risk of flash droughts in every major food-growing region in coming decades, new research shows

Published in Science & Technology News

Flash droughts develop fast, and when they hit at the wrong time, they can devastate a region’s agriculture.

They’re also becoming increasingly common as the planet warms.

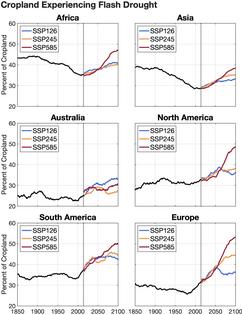

In a new study published May 25, 2023, we found that the risk of flash droughts, which can develop in the span of a few weeks, is on pace to rise in every major agriculture region around the world in the coming decades.

In North America and Europe, cropland that had a 32% annual chance of a flash drought a few years ago could have as much as a 53% annual chance of a flash drought by the final decades of this century. The result would put food production, energy and water supplies under increasing pressure. The cost of damage will also rise. A flash drought in the Dakotas and Montana in 2017 caused US$2.6 billion in agricultural damage in the U.S. alone.

All droughts begin when precipitation stops. What’s interesting about flash droughts is how fast they reinforce themselves, with some help from the warming climate.

When the weather is hot and dry, soil loses moisture rapidly. Dry air extracts moisture from the land, and rising temperatures can increase this “evaporative demand.” The lack of rain during a flash drought can further contribute to the feedback processes.

Under these conditions, crops and vegetation begin to die much more quickly than they do during typical long-term droughts.

In our new study, we used climate models and data from the past 170 years to gauge the drought risks ahead under three scenarios for how quickly the world takes action to slow global warming.

If greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, power plants and other human sources continue at a high rate, we found that cropland in much of North America and Europe would have a 49% and 53% annual chance of flash droughts, respectively, by the final decades of this century. Globally, the largest projected increases would be in Europe and the Amazon.

Slowing emissions can reduce the risk significantly, but we found flash droughts would still increase by about 6% worldwide under a low-emissions scenario.

...continued

Comments